China Telecom Americas, the American subsidiary of China's largest telecommunications enterprise, is now faced with what is likely the greatest threat to its business operations in the United States. In less than a week, the company will have to present arguments that could determine the fate of all its U.S. operations.

Amid an intensifying exchange of hostilities between Beijing and Washington, the Trump administration has once again targeted Chinese companies in its quest to eliminate so-called "national security threats."

Referring to the "sophistication and resulting damage of the Chinese government's involvement in computer intrusions and attacks against the United States," the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) last month issued so-called show cause orders to China Telecom Americas, China Unicom Americas, Pacific Networks Corp and its wholly owned subsidiary ComNet (USA) LLC, directing them to explain why it should not start the process of revoking authorizations enabling their U.S. operations.

The orders came as the U.S. Justice Department and other federal agencies have been strongly recommending the FCC to revoke China Telecom's ability to operate in the U.S. Such recommendations were issued due to concerns including "inaccurate public representations by China Telecom concerning its cybersecurity practices", "its vulnerability to state exploitation for economic espionage and disruption and misrouting of U.S. communications" and "the Chinese government's role in malicious cyber activity that threatens U.S. national security."

In response, China Telecom Americas' Director of Corporate Communications Ge Yu categorically denied these allegations and said "the company has always been extremely cooperative and transparent with regulators.”

"In many instances, we have gone beyond what has been requested to demonstrate how our business operates and serves our customers following the highest international standards," Ge said. "We look forward to sharing additional details to support our position and addressing any concerns."

China Telecom Americas' U.S. operations

Should the FCC deliver a verdict in line with the growing antagonism within the Trump administration, China Telecom Americas' very existence in the United States could be ended once for all.

The company, which obtained its license to operate in the U.S. in 2001, has offices in 31 countries across the continents and offers a variety of telecommunications services to both businesses and individual consumers. With FCC approvals, it is authorized to provide communications, data, television and business services in the U.S. as a facilities-based common carrier.

But the firm only offers very limited business to consumer (B2C) services to individual customers mostly comprised of Chinese nationals travelling to the U.S.

A visitor from China looks at her mobile phone in New York City, U.S., April 4, 2013

A visitor from China looks at her mobile phone in New York City, U.S., April 4, 2013

"As the company does not own any physical networks or infrastructure equipment in the U.S., its B2C items have been confined to network services via a mobile virtual network operator(MVNO)," Jeff Fieldhack, a telecommunications expert from Counterpoint Research told CGTN.

To provide services as an MVNO, China Telecom Americas enters into business agreements with U.S. network operators such as Verizon and AT&T to obtain bulk access to network services at wholesale rates, then sets retail prices independently.

"It has been difficult for MVNOs to gain profits in the country," Fieldhack said. "Dozens of operators have tried and gone out of business. Only a handful have succeeded in gaining subscribers but they are also losing money."

Its business to business (B2B) projects, on the other hand, enjoy a lot more market potentials. By offering VPNs, cloud services, and data centers to Chinese tech companies operating in the U.S., China Telecom Americas can help store and manage their data, as well as smooth the internet gateway between the U.S.-based servers of these firms and Chinese internet users.

"Chinese companies that own servers in the U.S. would certainly need these services, as it would be incredibly slow for users from China to browse their websites if the firms did not acquire VPNs to reroute their IP addresses," said Guo Pengfei, an IT expert specializing in informatization. "The same goes for those who need their data managed by a specialized provider in order to save the costs for self-managing."

With a growing number of Chinese tech companies edging closer to the U.S. market, the demand for such services is also on the rise, leaving a potentially vast market accessible to the Chinese telecommunications giant.

"Though its B2B operations are still in early developing stages and only retain a very low market share, the FCC revocation of its license would not only wipe out the company's existing operations but also smother all its business opportunities in the U.S.," said Fieldhack.

The lingering debate on 'national security'

The potential forced exit of China Telecom Americas and the three other operators came at the back of U.S. blacklisting Chinese tech giants Huawei and ZTE last year.

Though citing the same concerns for national security, Washington's real motives behind the injunctions were much contested. As U.S. President Donald Trump made it explicit at the time that whether Huawei and ZTE would be banned was contingent on China backing down its confrontational approach in the trade disputes, it raised questions as to whether there really was a security threat.

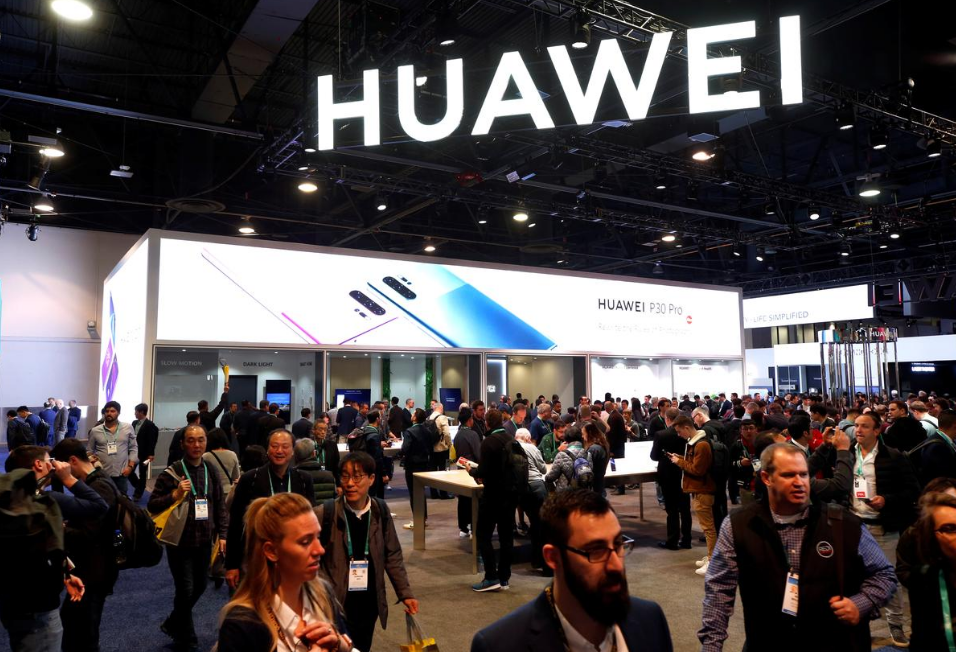

The Huawei booth is shown during the 2020 CES in Las Vegas, U.S. January 7, 2020. /Reuters

The Huawei booth is shown during the 2020 CES in Las Vegas, U.S. January 7, 2020. /Reuters

"The degree to which the president links security and trade makes one question the legitimacy of security issues," said Dr. Mark Cohen, the director of Asian IP Program at UC Berkeley School of Law. "If it were a national security issue, it wouldn't be linked to trade."

While this time the White House did not associate the move against the four telecommunications operators with the largely subsided trade war, the perceived "security threats" could also be put into question.

"Right or wrong, there is fear of espionage at both the point of network infrastructure (Huawei) and transmission (China Telecom)," said Fieldhack from Counterpoint. "Even experts are locked in a debate over whether this is a real threat or the current administration is using companies such as Huawei and China Telecom as bargaining chips for Phase 2 of the China-U.S. trade negotiations."

The Trump administration recently delivered another blow to Huawei with new tech restrictions. On Friday, the Department of Commerce said it will bar Huawei and its suppliers from using American technology and software, a move that marked another escalation of Washington's push to battle with China for global technology dominance.

This came about a week before the deadline for the four telecommunications companies to submit their response to the FCC.

U.S. President Donald Trump arrives to address a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak press briefing in the Rose Garden at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 11, 2020. /Reuters

U.S. President Donald Trump arrives to address a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak press briefing in the Rose Garden at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 11, 2020. /Reuters

Apart from that, observers also say the sudden flirtation with the idea of evicting the four companies was likely the result of Washington venturing to politicize the issue. They suspect the Trump administration's propensity to fuel xenophobia is an attempt to secure more votes for the coming elections.

Though the "threats" are possibly nonexistent, it doesn't necessarily raise the prospect of Washington reversing its course.

As the federal government has the innate privilege to broadly define the threats based on their own considerations, exactly what types of operations pose security threats to the U.S. can be very murky. By pointing to the probability of state-directed espionage without delving into the technical feasibility, it essentially allows Washington to deem any operators as "security threats" as they see fit.

In the case of Huawei, Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) and declared a national emergency that would give the president the authority to regulate business decisions in response to a national threat.

"As long as the president declares that there is such a threat and identifies that threat, he can then invoke IEEPA and can take, really, a staggering range of economic actions and impose severe economic penalties on people or entities or countries that are designated as being associated in some way with that threat," said Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program, in an interview with NPR news.

When asked whether the nature and extent of the threat is totally subjective, Goitein said "it really is up to the president."

"The diverse U.S. departments have been trying to rid the telecommunications industry of any reliance on China for years," Tang Hao, an international relations professor at South China Normal University, told CGTN. "To consider whether a company poses security risks, they first look at the degree to which the company is associated with the state. That's why companies like China Telecom would be targeted."

(Cover image: China Telecom's logo. /Reuters)