Editor's note: CGTN's First Voice provides instant commentary on breaking stories. The daily column clarifies emerging issues and better defines the news agenda, offering a Chinese perspective on the latest global events.

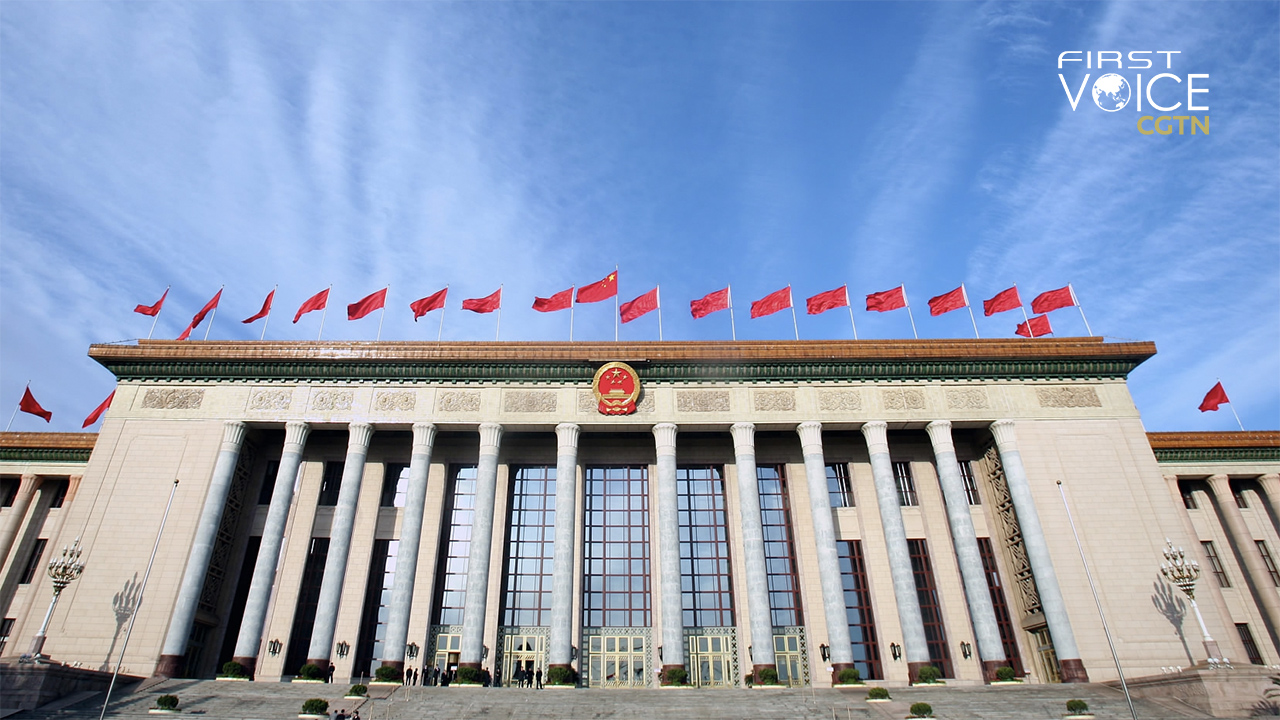

During his report on the government's work at the third annual session of the 13th National People's Congress on May 22, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang highlighted the necessity of building "sound" legal systems in Hong Kong and Macao Special Administrative Regions to safeguard national security.

Given what has transpired over the latter half of 2019 and early 2020, it wouldn't be unexpected that some are going to have a strong reaction. After the agenda was announced on May 21, the BBC published the headline "China security law 'could be end of Hong Kong.'" The Wall Street Journal's editorial board calls the move "China's forceful takeover of Hong Kong." U.S. senators are introducing a bipartisan bill that would impose sanctions on those who enforce this law in Hong Kong and penalize banks that do business with these individuals or entities. U.S. President Donald Trump vows to "address that very strongly" if the bill is passed and enacted.

There is a history to this controversy. Article 23 of Hong Kong's Basic Law declares that the region must enact national security laws to ban "treason, secession, sedition and subversion" against the Chinese government. However, an attempt to enact the law led to a widespread backlash in 2003. Opposition voices argued that such a law would erode freedom and autonomy in the region. Since then, there has been several attempts to try to enact the law that were shelved due to the public opposition. The law and the notion of freedom have become intertwined.

A screenshot of the BBC's reporting on the security law. /BBC

A screenshot of the BBC's reporting on the security law. /BBC

Granted, the HKSAR has a special political and legal status. Under the "One Country, Two Systems" structure, the region is, by law and by the spirit of the arrangement, given a high degree of autonomy. But Hong Kong is a part of China's sovereignty, and each country has its own laws against the four acts mentioned above. Countries like Spain, Germany and Italy all have specific legislation laying out the condition and penalty against these actions. In the U.S., the secession of a state can only be achieved legally through constitutional amendments. The alternative – armed rebellion – is to face the full force of the United States Armed Forces.

Hong Kong's special legal status makes the Chinese mainland's criminal law unable to be applied in the region. Specific laws and punishment against secession, as described by Li Jianxing, a law professor at East China Normal University and assistant prosecutor of the Zhuhai Municipal People's Procuratorate Li Ziwen, is "hard to find" in Hong Kong's legislation. The NPC has the constitutional right to oversee and be the final interpreter of all laws within China, and Hong Kong, despite its special relationship with the Chinese mainland, is within the parameter of its authority. It is the HKSAR authorities' constitutional duty to protect the integrity of China and safeguard the nation's security.

It might be noticed that freedom, though cherished and pursued by all, isn't necessarily part of the issue. A major modern country, regardless of its political system or governance structure, has to have the legal power and mechanics to protect its integrity and security. China is still in the process of reforming its rule of law. What kind of reform would it be if it doesn't include safeguarding the country?

Anti-government protesters set fire to one of the entrances of the metro station at Causeway Bay in Hong Kong, China, October 4, 2019. /Reuters

Anti-government protesters set fire to one of the entrances of the metro station at Causeway Bay in Hong Kong, China, October 4, 2019. /Reuters

But the weight of the issue also means that the laws are complicated, layered and hard to interpret by the general public. It is easy to be attracted to words and ideas like "freedom," "democracy" and "autonomy" even when the subject might have nothing to do with them. The New York Times published an article titled "Is this the end of Hong Kong," saying that the security law "sends the message that expression of political dissent or freedom of speech in Hong Kong are now at greater risk than ever," and "chilling effects like self-censorship or reluctance to speak out may be likely" even if there is no government-directed erosion on the freedom.

Well, there shouldn't be any doubt that inciting treasonous acts and rhetoric cannot be tolerated. Expression of dissent is not the same as trying to use violence to force the government into concessions or allowing the region to become independent. Just as foreign powers used the idea of freedom to rile up protests last year, all the provocateurs need to do to incite mass opposition against the bill is to make an emotional connection between the bill and the idea of being suppressed or deprived. What the bill actually means requires calm and clinical analysis, something hard to achieve when people are chanting within a crowd, throwing bricks at the elderly or setting subway stations on fire. And to be honest, if the goal is subterfuge and sabotage, telling people to be calm and clinical doesn't necessarily serve the purpose, does it?

Scriptwriter: Huang Jiyuan

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)