China's first-ever civil code is making waves at this year's Two Sessions, incorporating legal innovations and revisions to existing marriage and family laws that could herald significant changes in Chinese society. These massive revisions are partly in response to spiking divorce rates, a record low birth rate, an aging society, and many other problems amid sweeping socioeconomic changes. But some adaptations have caused controversy.

Let's take a closer look at what clauses concerning marriage and family in the draft civil code are making waves and how these clauses took shape.

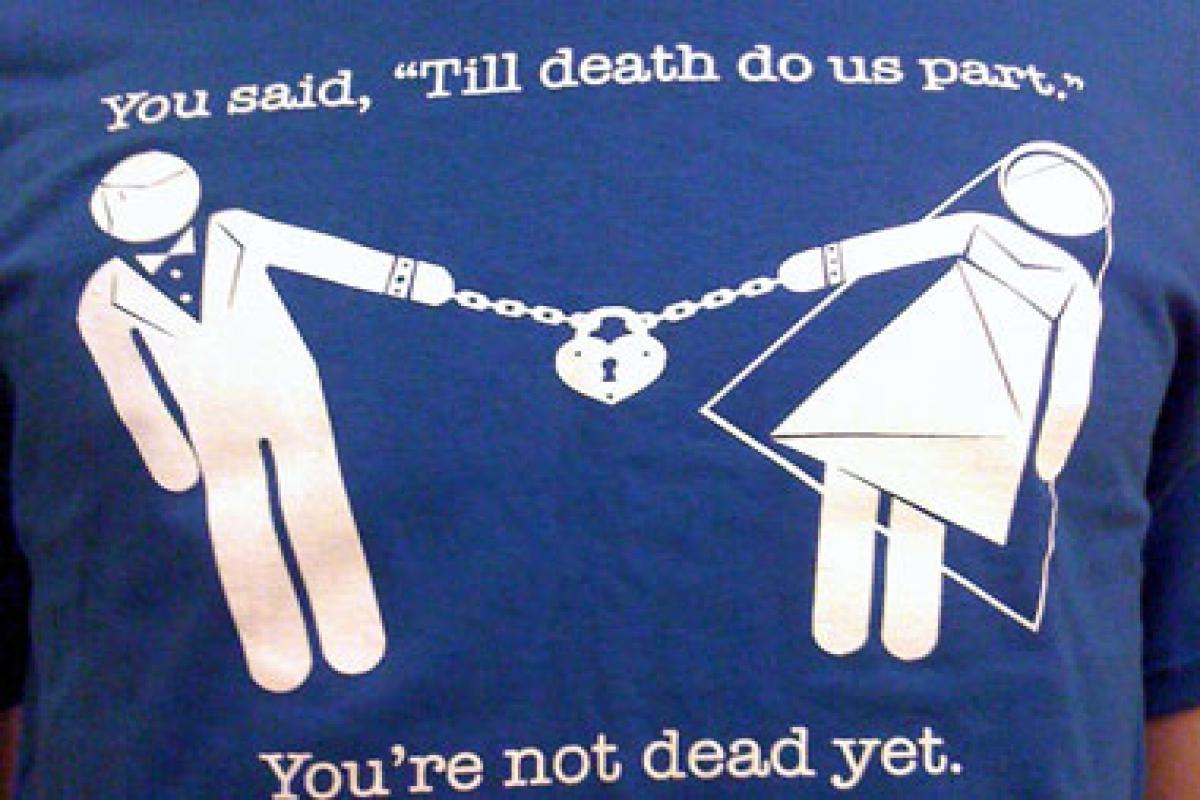

"Cool-off" period before divorce

One clause that netizens aren't cool with is a 30-day "cool-off" period for couples seeking uncontested divorces. The divorce rate in China has been on the rise since the turn of the century, reaching 3.2 divorces for every 1,000 inhabitants in 2018. Statistics from the Ministry of Civil Affairs show that in 2019, some 9.47 million couples got hitched while 4.15 million couples parted ways. That's kind of a watershed as it was the first time the number of registered married couples dropped below 10 million.

Chinese lawmakers lengthened the "cool-off" period hoping to reverse this trend. Some divorces happen on a whim, with both parties regretting their decisions afterward. Such a period exists in the U.S., Canada, the UK, and an increasing number of countries. In South Korea, the rate of divorce withdrawals rose from 6 percent to 23 percent just six months after the period was put in place.

"A 'cooling-off' period before you make the final decision to break up from your loved one will hopefully raise young couples' awareness of responsibility toward marriage," said Li Yinhe, a sociologist and member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, during an interview with CGTN.

First proposed by Chinese legislators in 2018, the rule had drawn public backlash, with many worried that it would make a spouse suffer for 30 more days, especially in cases of family violence, bigamy, or marital rape. However, lawmakers agreed to apply the rule only to uncontested divorces instead of a divorce petition filed in court, three times as many people express objection compared with those who agree in a recent poll conducted by The People's Daily Online.

Lowering the legal age for marriage

As the law stands, men can marry only at 22 years old while the age is 20 years old for women, a rule that has been in place since 1981. However, minors become adults at age 18 in the country. With fewer people getting married and a population whose average age continues to increase, there have been calls for the marriage age to be lowered to expand the pool of bachelors and bachelorettes for marriage. Despite the discrepancy between one's coming of age and the eligible age for marriage, there are still many voices advocating against change.

Last October, when Chinese lawmakers reviewed the draft civil code for the third time, they decided not to change it. But it's been brought to the spotlight again in the wake of a rapidly aging society. China's birth rate plunged to a record low since 1961 (10.5 births per 1,000 couples in 2019 according to the data from the National Bureau of Statistics), while the marriage rate has recorded a straight decline since 2013. In the first half of 2019 alone, the number of marriages declined by 7.7 percent.

A rise in the portion of women making up the workforce, economic affluence, and the rising cost of raising children are among the reasons for this phenomenon, which, though a symbol of social progress, is poised to slow consumer spending and exacerbate the looming labor shortage.

But some 60 percent of people polled last June objected to lowering the age for marriage. "It's not that rational to lower the age to tie the knot to deal with an aging society and boost the economy," noted Li.

Marriage can also end in annulment

Current law stipulates that one cannot marry someone deemed to have a disease that would make one unfit for marriage. The civil code draft proposes to change this law by allowing this union given that both parties are aware that the individual has such a disease.

Even if one hides their medical history before marriage, there is recourse other than divorce – a legal union can be annulled as if it didn't happen in the eyes of the law if a party conceals an illness that would be detrimental to married life. Not telling your spouse that you have a mental illness, for example, could be grounds for annulment in Chinese law.

However, proving that there was concealment or even getting the illness diagnosed by a medical authority is easier said than done. Depending on the situation, a spouse who wants to prove that there was concealment or that their partner did indeed have an illness before the marriage may have to get the latter's cooperation, which would be a difficult proposition if the current state of the relationship is less than amicable.

Can the law protect an unmarried couple living together?

Another challenge to a legal convention that has engendered longstanding debate is recognizing non-marital cohabitation. As the number of people living together like partners without marrying grows, some are seeking the legal protections afforded to married couples, especially when disputes arise over children or inheritance. Whether the law can be changed to accommodate the complex relationships in Chinese society is closely watched.

Can grandparents visit grandchildren after a messy divorce?

While it's unclear whether the maxim "it takes a village to raise a child" applies to modern Chinese society, grandparents still play a vital role in raising their grandchildren, helping parents with this most sacred of responsibilities and allowing them to focus on their careers. So when a couple divorces, it's more than a decoupling of two individuals. Those on the losing side of a custody battle will have tremendous difficulty seeing their grandchildren, as the law is still unclear on visitation rights regarding grandparents. Previous drafts of the civil code stipulated that grandparents inherit the respective visitation rights upon a parent's death. Critics argue that giving such rights to grandparents whose son or daughter does not have custody of the child may interfere with the development of the grandchild.

(Cover image designer: Gao Hongmei)