Indian and Chinese national flags flutter side by side at the Raisina hills in New Delhi, India, September 16, 2014. /Xinhua

Indian and Chinese national flags flutter side by side at the Raisina hills in New Delhi, India, September 16, 2014. /Xinhua

Editor's note: Josef Gregory Mahoney is a professor of politics at East China Normal University. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The world we live in today has a number of unfortunate descriptions with increasing currency. These include of course the COVID-19 pandemic, with which we are already too familiar and sick of in every respect, but we also have to face exhausting terms like "great power competition," "trade war," "Cold War 2.0," and "decoupling."

Additionally, we have various forms of social unrest and protests, ongoing in the U.S., for example, with concerns for racial and social injustice. And always, lurking, the terms "climate change" and "global warming."

Increasingly a concept previously unknown to many has been used to describe these problems and their global intersections. The concept is "VUCA world" — "V" stands for volatile, "U" stands for uncertain, "C" stands for complex, and "A" stands for ambiguous.

In fact, this term was first introduced in 1987 by two scholars developing theories about leadership. It found wider usage when the U.S. military picked it up to describe post-Cold War developments, and it became an entrenched part of military lexicon especially after the 9/11 attacks.

VUCA vs. a new world order

Are we living in a VUCA world spinning out of control, or are we witnessing the birth of a new world order?

Without question, 9/11 and the so-called "War on Terror" that followed, including especially the American wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but also punctuated by the U.S.-instigated Global Financial Crisis of 2008, can be viewed as signaling three things.

First, the "end of history" and "peace dividend" theses that many in the U.S. embraced with the dissolution of the Soviet Union amounted to misguided and misguiding optimism and hubris. And it was America who squandered what was presented as historic opportunities, if in fact they were ever even possible given use of destructive rubrics like the "Washington Consensus" and the hegemonic position of the U.S. dollar as the supranational currency, which not only put many in the world at the mercy of the U.S. dominated international organizations, but also subjected them to the health of the U.S. economy and the whims of both the Federal Reserve and the White House.

Second, above all, the American wars on terror and the economic and political problems that emerged following the crisis in 2008 demonstrated not only the limits of American power, insomuch as these wars failed to achieve strategic goals and objectives and instead produced the opposite, and further as the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the full extent to which the American economy had become a shell game played with funny money, it also posed a question that bedevils many now, including even Francis Fukuyama – that maybe the U.S. was never the example it was taken to be, but in fact the locus of many of the world's problems, and further, deeply entrenched against the sort of positive change that could undermine its global hegemony.

Third, while the term "VUCA world" seems like an apt description, perhaps what we are seeing today is not the end of globalization, as The Economist magazine lamented on a recent cover. Rather, instead of a collapse, maybe we are seeing the emergence of a new world order: increasing order where it was previously deficient and the decline of order where it once ruled. Thus, it might be right to say that this is a VUCA world, but it's not a world without sense and order, even if order is to be found increasingly in places like China and India and less so in the U.S. and Europe.

Strategic convergence

In 1954, China and India codified in treaty form the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, including mutual respect for each other's territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference in each other's internal affairs, equality, mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. Although India and China experienced rough patches after that initial treaty, since the 1970s, the Five Principles have increasingly become the norm guiding relations between the two countries.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the establishment of China-India diplomatic relations. While relatively minor border disputes remain in some remote areas, these have over time become exceptionally well-managed, despite sometimes being hyped as significant conflicts in proto-nationalist and anti-China global media.

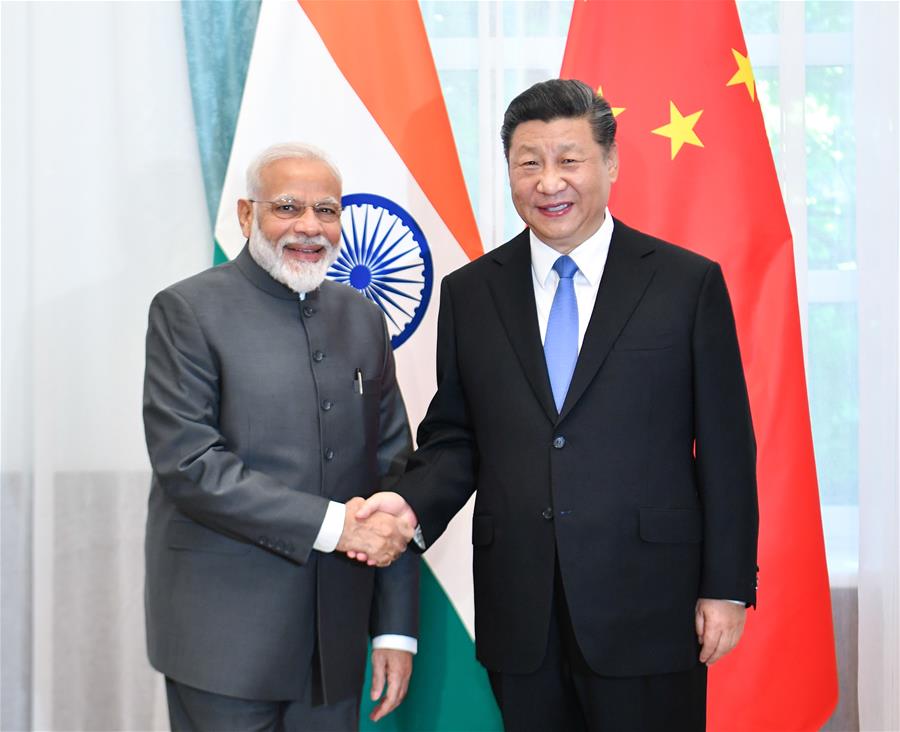

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, June 13, 2019. /Xinhua

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, June 13, 2019. /Xinhua

History teaches us that the Five Principles are closely associated with the Bandung Conference in 1955, which concluded that countries seeking to overcome their colonial experiences and establish themselves in an otherwise dangerous world would need to create foreign relations that found a new way forward, away from the old logics of global superpowers, imperialism and hegemony.

Unfortunately, for a time, that vision was hard to achieve, as the Cold War did much to derail the non-aligned movement that followed, with the U.S. and the USSR dividing the world into competing camps.

Now, with the U.S. once again openly encouraging such a dark path against China, and indeed, as some rather cynically argue that great power competition is one that is always inclined to war, we might instead argue that the growing positive relationship between China and India represents a renaissance of the Bandung vision.

In fact, one can argue that positive relations between India and China, the modern forms of two ancient and very large civilizations, defy three major theses that have misguided Western thinking, including Fukuyama's "end of history," Samuel P. Huntington's "clash of civilizations," and Graham Allison's "Thucydides trap."

In an article published in the Indian Military Review in 2018, I argued that India should carefully consider and ultimately reject America's enticements to join a proposed "Indo-Pacific" anti-China security pact.

Unsurprisingly, wise leadership in Delhi appears to have reached similar conclusions. Although the Indian government has improved its relations with Washington, these too have been fraught with trade threats. Meanwhile, it has also preserved and strengthened its relations with China. This is a difficult balancing act in these times given U.S. efforts to divide and isolate, but India's efforts and results are commendable.

Moving forward

Although trade between India and China has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, trade and investment between the two countries has been increasing for many years and will continue to do so. Both India and China excel in math education and produce exceptional accountants, and they already know first-hand that the benefits of economic cooperation far outweigh the quixotic calls that India should pursue a Trump-encouraged decoupling with China.

Indeed, China is a major trading partner throughout South Asia, and while some have worried the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) would undermine India strategically, particularly as it moved through Pakistan, it appears more likely that the BRI will also serve India's economic and security interests. Promoting growth and development in Pakistan is helping create transformations that promote greater security for all. Further, it is also providing an avenue for India to establish durable overland links with China, Central Asia, Russia, and even Europe that will facilitate even more Indian and regional growth and development as well as peace.

The spirit of the Five Principles lives on today and finds new life in President Xi Jinping's call for a "shared future for mankind" and Prime Minister Narendra Modi's responses in kind. We cannot underestimate the value of preserving peace and development between these two Asian giants. Doing so brings security to nearly half the world's population and creates incredible opportunities for human development and progress, made all more pressing now as the world struggles to recover from the pandemic.

Consequently, while the U.S. and others flounder and risk reactionary responses to current crises, New Delhi and Beijing must and will continue to chart their own course forward in ways that build on their progress-to-date and further actualize their countries' still incredible upward potential.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)