Editor's note: This is the 79th article in the COVID-19 Global Roundup series. Here is the previous one.

As the coronavirus continues leaving a trail of devastation behind globally, another deadly virus is rearing its ugly head in South Asia – dengue fever.

The monsoon months in the region, between late May and September, bring much needed rain but also mosquito-borne diseases. And this includes dengue fever, an illness caused by an infection with a virus transmitted by the Aedes mosquito, which currently has no cure.

Aedes aegypti is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by white markings on its legs and a marking in the form of a lyre on the upper surface of its thorax. / Reuters

Aedes aegypti is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by white markings on its legs and a marking in the form of a lyre on the upper surface of its thorax. / Reuters

Even without the backdrop of a global pandemic, dengue cases have seen a dramatic spike in the past decade due to erratic storms, rising global temperatures, and unplanned rapid urbanization. Last month alone, India and Bangladesh were hit by the biggest storm in 20 years, forcing five million to evacuate.

An estimated 400 million dengue infections happen around the world each year, killing some 25,000 people annually. According to the World Health Organization, 2019 saw the most number of cases reported, with Asian countries bearing approximately 70 percent of the disease burden.

Delayed dengue response, record hike in cases

There are worries that a wave of dengue outbreak will further strain healthcare and sanitation resources in the region, especially in countries that are already reeling under the pressure of COVID-19.

In India, pre-monsoon preparations to prevent and anticipate mosquito-borne diseases through vector control and public education were delayed due to a heightened focus on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fumigation being carried out in a Delhi, India, to control breeding of mosquitoes. /AP

Fumigation being carried out in a Delhi, India, to control breeding of mosquitoes. /AP

According to a report from AFP, thousands of Mumbai public health workers who fumigate neighborhoods to kill disease-carrying mosquitoes had to delay those crucial efforts for two months to focus on sanitation instead.

Lockdown measures may also be contributing to increased mosquito larvae in areas such as unmanned construction sites, where pools of stagnant water form due to rains, creating the perfect breeding site for these mosquitoes, said Ruklanthi de Alwis, Senior Research Fellow, Emerging Infectious Diseases program at Duke-NUS Medical School to CGTN.

"There are oil based insecticide that can be used, but when the rain comes it washes them away, and we get stagnant pools of fresh water. It's different if you're working there 24/7 as compared to when you only check a couple of days," Ruklanthi elaborated.

Due to a confluence of factors besides COVID-19, some countries in Southeast Asia were already looking at a record breaking year for the number of dengue cases.

In Indonesia, which now has the highest number of coronavirus cases in Southeast Asia, close to 40,000 people were diagnosed with the disease in the first three months of this year, a 15.7 percent rise compared with the same period last year.

Meanwhile, Singapore is seeing a record high of dengue cases in seven years. More than 10,000 people in the city-state have been diagnosed with the mosquito-borne disease, compared to 2013 when 22,170 contracted the disease.

Threats of misdiagnosis, separate outbreaks

Dengue symptoms are almost indistinguishable from COVID-19 – both present symptoms like fever, breathing difficulties, headaches, fatigues and a loss of appetite.

Complicating things further, it's been reported that COVID-19 patients can get false-positive results from rapid serological testing for dengue.

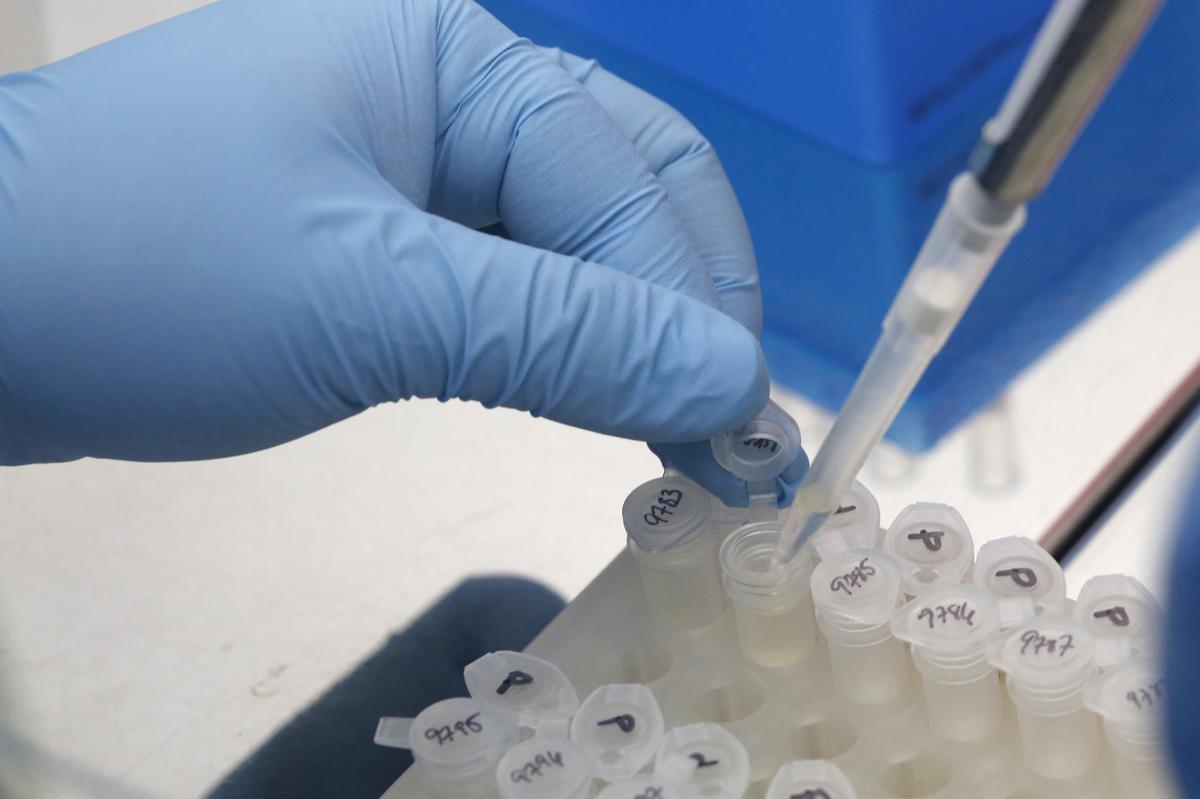

A medical researcher works on results of tests for preventing the spread of the Zika virus and other mosquito-borne diseases at the Gorgas Memorial institute for Health Studies laboratory in Panama City. / Reuters

A medical researcher works on results of tests for preventing the spread of the Zika virus and other mosquito-borne diseases at the Gorgas Memorial institute for Health Studies laboratory in Panama City. / Reuters

Two patients in Singapore were misdiagnosed with dengue in March, only to be later classified as COVID-19 patients. But now, there may also be the possibility of misdiagnosis the other way round, said Ruklanthi.

"Very early on, there was misdiagnosis, because there was not as much COVID but there was dengue. So they misdiagnosed dengue. But now it could be the other way round, they may be misdiagnosing dengue patients as COVID."

On top of that COVID-19 and dengue have different disease progression albeit having similar early symptoms. The former develops respiratory symptoms like coughing, while the latter progresses into hemorrhagic fever right shock syndrome for severe cases, meaning diagnosis has to be done early on since treatments are different.

The two also affect different segments of the population, which may prove to be a double whammy for countries.

"This [dengue] is primarily a pediatric disease, as in children like teenage or younger children, form the bulk of infections...whereas for COVID, it's really the senior people, the people with comorbidities who are the ones affected."

Strategies differ in developed and developing countries

As countries in the region struggle to contain both deadly viruses, the most effective strategy will be to test patients at fever clinics for both diseases because they will need to be isolated.

However, this may not be plausible for developing countries that may not have the necessary resources. But there is a silver lining in that dengue is a familiar enemy.

"Dengue is an environmental disease and countries have developed expertise to deal with it on a certain level. But coronavirus is something new that they have limited experience with," Jayaprakash Muliyil, chairman of the scientific advisory committee of the National Institute of Epidemiology in India, told CGTN Digital.

In dealing with the twin outbreaks, Muliyil cited "age, timing, and location" as three key factors in deciding how to approach patients who go to fever clinics.

If a young man shows up in the hospital at a time where a spike is expected, Muliyil explained, he would test for dengue first. Conversely, if an older person turns up, he will test for COVID-19, given they are more susceptible to severe cases of coronavirus.

Ruklanthi is worried, however, that this familiarity may breed a false sense of security, leading both authorities and the public to not take it seriously.

A poster of wiping out mosquitoes as a residential estate in Singapore. /Creative commons

A poster of wiping out mosquitoes as a residential estate in Singapore. /Creative commons

For developing countries, especially, she feels the best way to prevent a full-blown outbreak will be to stem it before the disease even begins to overwhelm healthcare systems through vector control and public education.

"We're all very good now at wearing our masks or staying away from other people if we have any sort of cough. We're very good now at washing our hands...but none of those control measures is really having an effect on the dengue," she said.

As of now, infections of both dengue and COVID-19 have yet to be reported. But a possibility still remains, and may mark more challenging times ahead for healthcare systems in the region that are already under pressure.

(Cover image: A sanitation worker fumigating a neighborhood in the Philippines. /Reuters)

(CGTN's Alok Gupta also contributed to this story)