The world is waiting for the latest breakthrough in COVID-19 vaccine development. Stephane Bancel, chief executive officer of Moderna, one of the frontrunners in the vaccine race, said he is cautiously optimistic a vaccine for COVID-19 will be on the market by next year.

But in the midst of the global pandemic, a geopolitical race to prioritize immunization of each country's own nationals is on the rise. High-income countries are scrambling to secure pre-production contracts with vaccine manufacturers to reserve supplies. Some fear that export control would be in place once COVID-19 vaccines become available.

"Low-income countries would be in a disadvantaged position on access to COVID-19 vaccines, especially those early ones, under an every-nation-for-itself approach," said Zhang Li, director of Strategic Innovation and New Investors Hub at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, at a recent media briefing session on immunization and the role of multilateral cooperation hosted by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

A perennial dilemma in distribution

To stem the spread of the virus, a vaccine is regarded as the most effective solution and holds the key to reopening economies.

But there are many steps to take before vaccines can achieve the full impact, said Li Yinuo, director of China Country Office at Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. After research and development, many issues need to be coordinated on the international level, such as ramping up production quickly, ensuring equitable distribution, and prioritizing vaccination for medical workers and other high-risk groups.

There are about 126 COVID-19 vaccine candidates currently registered with World Health Organization, research suggests that historically, vaccine programs that have not yet entered human trials have just a seven percent probability of succeeding, which rises to only 17 percent once they enter human trials.

This poses high financial risks for pharmaceutical and life science companies to scale up production before they know the safety and efficacy of the vaccines, let alone most manufacturers are unlikely to have the production capacity to meet massive demands, said Zhang from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

A researcher at the University of Pittsburgh works on a COVID-19 vaccine candidate, Pennsylvania, U.S., March 28, 2020. /Reuters

A researcher at the University of Pittsburgh works on a COVID-19 vaccine candidate, Pennsylvania, U.S., March 28, 2020. /Reuters

Since much of the research and development are supported by governments and corporations, some argue that supplying vaccines first to the countries that fund the research is justified.

French pharmaceutical firm Sanofi recently came under fire for suggesting that its vaccines would be made available to the American market first because of partial funding from the U.S. It later backtracked and said that the company has always been committed to making its vaccine accessible to everyone, especially in unprecedented circumstances.

Just as what is seen amid the global race to secure personal protective equipment, the tension between supplying medical resources to everyone in need and prioritizing each country's domestic needs has been an age-old struggle.

Why a multilateral framework is key

To secure immunization access for developing countries, a few global initiatives have been proposed.

"Gavi was set up in 2000 to address a market failure where commercially available vaccines were not reaching lower-income countries," said Zhang from Gavi. "By aggregating demand from developing countries and pooling donor support for immunization, Gavi has been able to create a viable market where one did not exist before."

The organization launched the Gavi Advance Market Commitment for COVID-19 Vaccines, a financing instrument that will use official development assistance (ODA) funds from OECD donors to incentivize manufacturers through guarantees to ensure sufficient global capacity is ready to go as and when vaccines gain licensure.

By pooling the needs of higher-income and low-income countries together, the organization can buy large volumes of vaccines, ensuring that every country gains guaranteed access to them.

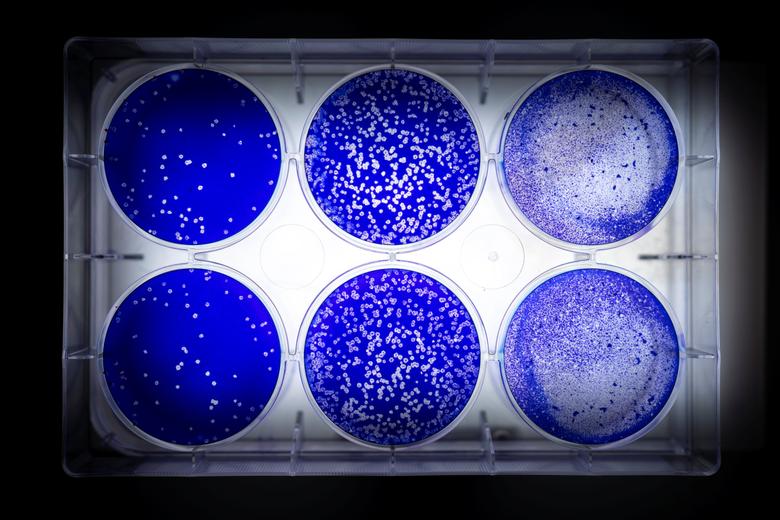

Cells are seen through a microscope inside a laboratory during a study on the coronavirus disease growth in animal cells in Bangkok, Thailand, May 25, 2020. /Reuters

Cells are seen through a microscope inside a laboratory during a study on the coronavirus disease growth in animal cells in Bangkok, Thailand, May 25, 2020. /Reuters

"Global coordination on production and distribution – pooling the needs of countries worldwide and assessing global production capacity – is the best way to address a shared global challenge," Zhang noted.

The World Health Organization (WHO) also launched a global initiative called "The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator," which aims to help speed up the development and production of vaccines and ensure its equitable distribution.

More than 140 world leaders and experts have signed an open letter before the World Health Assembly in May, calling on governments to make all vaccines, treatments and tests patent-free, mass produced, daily distributed and available to all.

China and the global public good

In a keynote speech delivered at the Extraordinary China-Africa Summit on Solidarity against COVID-19 on Wednesday, President Xi Jinping said that once the development and deployment of a COVID-19 vaccine is completed in China, African countries will be among the first to benefit.

This echoes his earlier statement at the recent World Health Assembly virtual meeting, when he said that vaccine development and deployment in China will be made a global public good.

During the summit, President Xi also said that China will work with Africa to uphold the UN-centered global governance system and support WHO in combating the coronavirus pandemic.

"For global public health crisis like COVID-19, no country can deal with it alone," said Wang Luo, director of the Institute of International Development Cooperation, Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation. "The pandemic has pushed China to realize the urgency and importance of participating in multilateral framework."

China's global health policy, historically, has focused on bilateral collaboration, with sending medical teams as the primary means of engaging in public health diplomacy.

A medical worker takes a sample for COVID-19 during a community testing, as authorities race to contain the spread of coronavirus in Abuja, Nigeria, April 15, 2020. /Reuters

A medical worker takes a sample for COVID-19 during a community testing, as authorities race to contain the spread of coronavirus in Abuja, Nigeria, April 15, 2020. /Reuters

Yet recent years have witnessed China stepping up investment in multilateral framework in public health. For example, funding from China to the WHO rose by 52 percent since 2014 to around 85 million dollars during the 2018-2019 two-year period. At the recent online summit to raise funds for Gavi, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang announced a 20-million-U.S.-dollar donation to the program.

On issues such as fund raising, project implementation and solution finding, multilateral approach that taps into the power of diverse actors, including corporations, non-governmental organizations, can bring innovative solutions, said Wang.

The global scramble to secure personal protective equipment as the coronavirus spreads, shows the danger of the my-nation-first approach. Panic buying, hoarding and misuse have put people most at risk of infection exposed to the virus.

Multilateral framework where the voices of the poor countries will be magnified, once pulled together, can bring us closer to an equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.