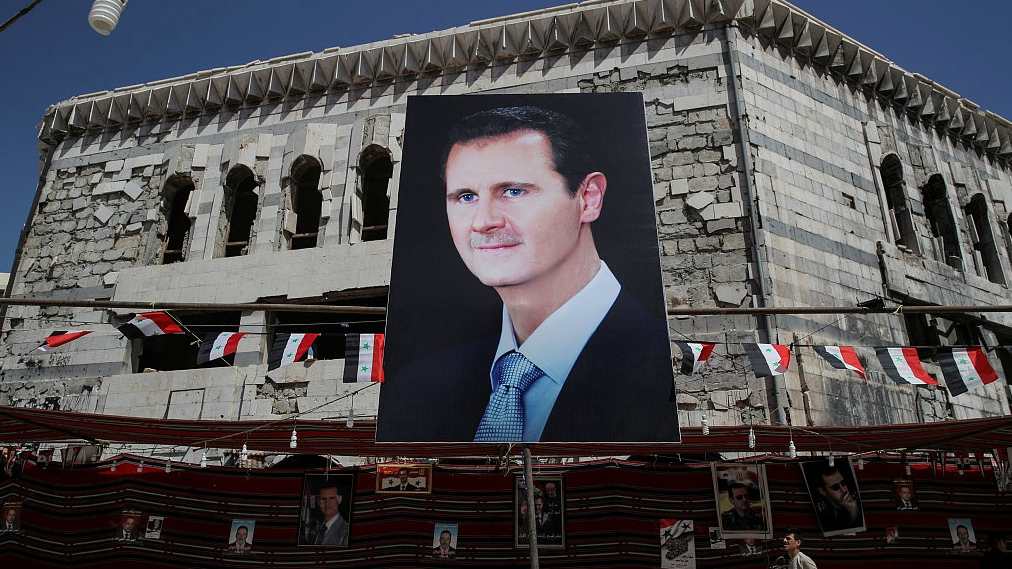

A banner depicting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Douma, outside Damascus, Syria, September 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

A banner depicting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Douma, outside Damascus, Syria, September 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

Editor's Note: Guy Burton is an adjunct professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Syria has recently experienced agitation at both the elite level and among its population. Despite these developments, it's so far unclear that either of these will be sufficient to destabilize current President Bashar al-Assad. At the same time, while Assad's situation seems presently secure, any changes at elite or mass level could prompt a reappraisal, along with the recent arrival of COVID-19.

That Assad was under threat was suggested by media reports concerning disaffection within the regime. Throughout Syria's war, differences within the leadership were few. Then last month it was reported that Assad had demanded his cousin, Rami Makhlouf, pay back taxes on his extensive business interests and seized a number of his assets.

Assad's move was interpreted as a way to demonstrate who held power in Syria. By taking on Makhlouf, Assad was challenging Syria's wealthiest figure. Even before the war began in 2011, he controlled over half the country's economy through direct and indirect holdings – much of it with the blessing of the political power.

Makhlouf responded with a series of online videos in which he claimed that Assad risked losing the support of the Alawite minority which dominates the Syrian political power. But if it was a call to arms, it hasn't yet been heard by a challenger within the regime.

The same may also be said about the protests and demonstrations that have taken place over the past few weeks. They are the most prominent to take place in government-controlled territory since the uprising which precipitated the war in 2011.

The origins of the current protests are chiefly economic. With more than 80 percent of the population below the poverty line, life has become even harder following rising food prices and cost of living. Whereas the exchange rate was around 50 Syrian pounds to one U.S. dollar in 2011, between the start of the year and today, it had risen from around 700 to 3,500 pounds.

A contributing factor to the hardship faced by Syrians is the financial crisis in Lebanon next door. Slowing capital flows and growing public debt since last October has not only led to the collapse of one government, but forced its successors to freeze accounts. That has been problematic for Syrians who put their savings in Lebanese banks and used its banking system to circumvent international sanctions against the country.

The economic situation is about to get worse for Syria too. On June 17, the U.S. Caesar Act came into force. It will impose new sanctions on the regime and individuals associated with it. It will also threaten third parties who are currently involved working in Syria or thinking of doing so. That will affect Assad's ability to attract investment for his country's postwar reconstruction.

For now, Assad seems likely to weather the storm. He has closed off any possibility of a challenge to his rule.

Inside the political power, there is no clear alternative to Assad. He has deliberately ensured it so, by regularly moving around those at the top, including those occupying the leading positions in the armed forces.

Vehicles run on a road in Damascus, capital of Syria, on June 18, 2020. /Xinhua

Vehicles run on a road in Damascus, capital of Syria, on June 18, 2020. /Xinhua

Meanwhile, neither of the regime's foreign backers, Russia or Iran, has shown much appetite for change. Although the Russians have reportedly been frustrated at the direction Assad is taking, they are neither able nor willing to force a move. In part this reflects a recognition that their position in Syria – and through it, their enhanced stature as a key diplomatic actor in the Middle East – owes much to their shared effort in winning the war.

As for Iran, Assad has faced little opposition anyway. Tehran has its own difficulties, including responding to the COVID-19 pandemic at home while dealing with the U.S. decision to re-impose sanctions after Washington withdrew from the international nuclear agreement.

Beyond the regime, Assad's position has been secured by years of war and virtual victory. The current demonstrations are far too weak to constitute a serious threat and face the threat of repression. Meanwhile, what remains of an armed opposition was effectively beaten back after 2015 and since late 2016 has been largely confined to the northern province of Idlib, which is where the remainder of the rebel groups are mostly based.

Other than Turkey, which has provided assistance to some of the rebels in Idlib, other regional powers have all but departed the Syrian war. Whereas Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE all previously provided much needed aid to the opposition, which has mostly come to an end. Since late 2018 there has been a rapprochement between Assad and some of the Arab Gulf monarchies.

With the main routes closed off then, Assad's continued position as president is secured. That said, this presumes that the current state of affairs remains in place and that there is no significant change of heart from within the regime or among its partners or greater pressure from outside, whether from an expansion of the protest movement or a revitalization of the armed opposition.

To these obvious variables is another, so far unconsidered element: namely, COVID-19. In contrast to the rest of the Middle East, the coronavirus arrived late in Syria, at the end of March. Today there are less than 200, although the real figure may be higher than reported, owing to a lack of tests owing to sanctions.

As the number of COVID-19 cases rise, it will put strain on the country's already ravaged and battered healthcare system. The expansion and intensification of COVID-19 may be felt across the whole of society, both in the population as a whole as well as in the leadership – although like elsewhere, the former is more likely to suffer the effects than the latter.

Should COVID-19 become a more prominent feature of the Syrian landscape in the second half of this year then, it could well play into the different factors at both the elite and mass level regarding Assad's political future. But if that does happen, it's more likely that Assad would face a challenge from within the regime than from outside, meaning that the predominant forces and structures would remain in place.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)