Editor's note: This is the 82nd article in the COVID-19 Global Roundup series. Here is the previous one.

02:48

Peru has recorded more than 8,000 fatalities so far, with over 260,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases, ranking as the eighth most heavily affected country in the world. Unlike the presidents of U.S. and Brazil, who have publicly defied social distancing and quarantine measures, Peruvian President Matin Vizcarra responded quickly when the coronavirus attacked.

On March 15, when the country only had 71 confirmed cases, he declared a national state of emergency, closed Peru's borders, ordered all to stay at home and mobilized the police and army to enforce it. It seems the Peruvian government prepared well to fight against the pandemic.

However, despite stringent quarantine measures, the coronavirus continues to spread across the country without any sign of fading. To make matters worse, due to the worsening economic situation and high unemployment rate caused by the pandemic, hunger rather than getting infected with the coronavirus now has become the number one enemy of the underprivileged Peruvians.

How did the coronavirus spread so much in Peru despite stringent quarantine measures?

A woman adjusts her mother's face mask at their house on the southern outskirts of Lima, Peru, May 28, 2020. /AFP

A woman adjusts her mother's face mask at their house on the southern outskirts of Lima, Peru, May 28, 2020. /AFP

Some people criticized that many people didn't follow the rules and they kept going out during the quarantine period. But those who ventured out argued that they have to feed their families. Some videos online show street vendors quarreling with police officers as they try to pull away hundreds of vendors.

Official data of 2018 show only 27.6 percent of the Peruvian population had formal jobs, while 72.4 percent of them worked in informal sectors, which means over 70 percent of the population doesn't have access to pension, medical, unemployment and maternity insurances. The severely imbalanced economic structure makes stay-at-home policy a paper talk.

Despite this, according to a 2018 government survey, about half of Peruvian households don't have a refrigerator, making it impossible for them to stay at home for long periods of time as food can get spoiled. As a result, when people ventured out to get food, busy food markets became hotspots of infection. In Peru's gastronomic capital Lima, spot tests showed most traders were asymptomatic carriers of the coronavirus.

Additionally, Lima, with more than eight million people, is built on a desert and receives hardly any rainfall. Some one million residents of the capital have no access to running water, making it less likely to wash hands frequently, one of the the primary prevention measures.

While the failed stay-at-home policy has already led to the presently surging number of COVID-19 infections, the unprecedented unemployment rate caused by the domestic quarantine measures and global economy recession are throwing many into poverty.

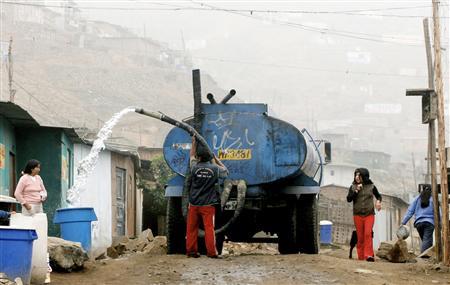

A man delivers water from a tanker in San Juan de Miraflores on the outskirts of Lima, Peru. /Reuters

A man delivers water from a tanker in San Juan de Miraflores on the outskirts of Lima, Peru. /Reuters

According to the Peruvian National Institute for Statistics (INEI), Peru's economy sank 40.49 percent year-on-year in April, its worst-ever percentage drop in output. The agency's monthly economic report also pointed out that the unemployment rate surged to 13.1 percent in May from seven percent in February of 2020. In Lima alone, about 2.3 million people lost their jobs. The increasing unemployment has caused poor families to fear hunger more than COVID-19.

To mitigate coronavirus impacts, the president in March released 26 billion U.S. dollars, worth around 12 percent of its GDP, to contain the disease, support citizens and resume production. The package includes a set of measures to help poor families: basic food baskets and a subsidy of around 220 U.S. dollars based on the family's financial status.

However, these government measures have backfired.

People line up in order to know whether or not they are beneficiaries. And according to INEI, 56 percent of Peruvian adults don't have a bank account, causing people to form long queues outside banks to receive government aid. During the process, cluster infections occurred.

According to several local news reports, the government relief is not only little to cover family needs but also slow as many are still waiting to receive the aid. As the coronavirus continues to spread in the country, the post-pandemic future looks increasingly bleak.