Migrant workers arrive to board a train back home during a nationwide lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Mumbai, India, May 8, 2020. /Xinhua

Migrant workers arrive to board a train back home during a nationwide lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Mumbai, India, May 8, 2020. /Xinhua

Editor's note: Anne O. Krueger, a former World Bank chief economist and former first deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund, is Senior Research Professor of International Economics at the School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, and Senior Fellow at the Center for International Development, Stanford University. The article reflects the author' opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

After ravaging the developed world, COVID-19 is now devastating developing and emerging-market countries, most of which lack medical and financial capacity to combat the pandemic and its economic effects.

For advanced economies, the first line of defense has been social distancing, hand washing, face masks, and widespread lockdowns. But for poorer countries, replicating this response is virtually impossible. Housing tends to be overcrowded, and face masks and soap are scarce. Moreover, water sources and sanitation facilities are often shared and situated in narrow alleys, and many poor people must leave their homes daily to access them or to purchase food. Hence, for poor people who live hand to mouth, an enforced lockdown amounts to a sentence of penury and possibly starvation.

Conditions in many parts of India illustrate the catastrophe that has been unfolding across developing and emerging markets. When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared a sudden lockdown in late March, millions of migrants lost work and were forced to return to their villages hundreds of miles away. With no means of transportation, they simply started walking, spreading the virus as they went.

Now that India's lockdown has been lifted, and, with hospital capacity having reached its limits, even people presenting with severe COVID-19 symptoms are being turned away. The Washington Post reports that, "Before the pandemic hit, India had only 0.5 hospital beds per 1,000 people … compared with 3.2 in Italy and 12.3 in South Korea." Mumbai, a city of 20 million, has just 14 intensive-care-unit beds available for COVID-19 patients. And yet, by the end of July, India is expected to have at least 500,000 cases, up from an estimated 30,000 today.

The circumstances are just as dire in many other developing countries. In addition to lacking hospital capacity, most have little or no productive capacity for personal protective equipment (PPE), medicines, and other critical supplies. And while advanced economies and international institutions are coordinating financial support and debt relief for developing countries, this shortage of essential goods has yet to be addressed.

Making matters worse, at least 75 governments have imposed restrictions or bans on exports of medical supplies, prompting importing countries to start investing in their own capacity. Already, this is leading to a vicious circle in which export restraints encourage import restrictions and vice versa.

In normal times, markets would allocate these resources efficiently, with rising prices leading to lower demand and more supply. But that cannot happen in a global crisis; nor does it help simply to furnish developing and emerging markets with financing. Fresh funds would allow them to bid for supplies in global markets, but the effect would be to send prices higher. Ultimately, because the short-term supply of PPE and other products is inelastic, wealthier countries would crowd out the poor.

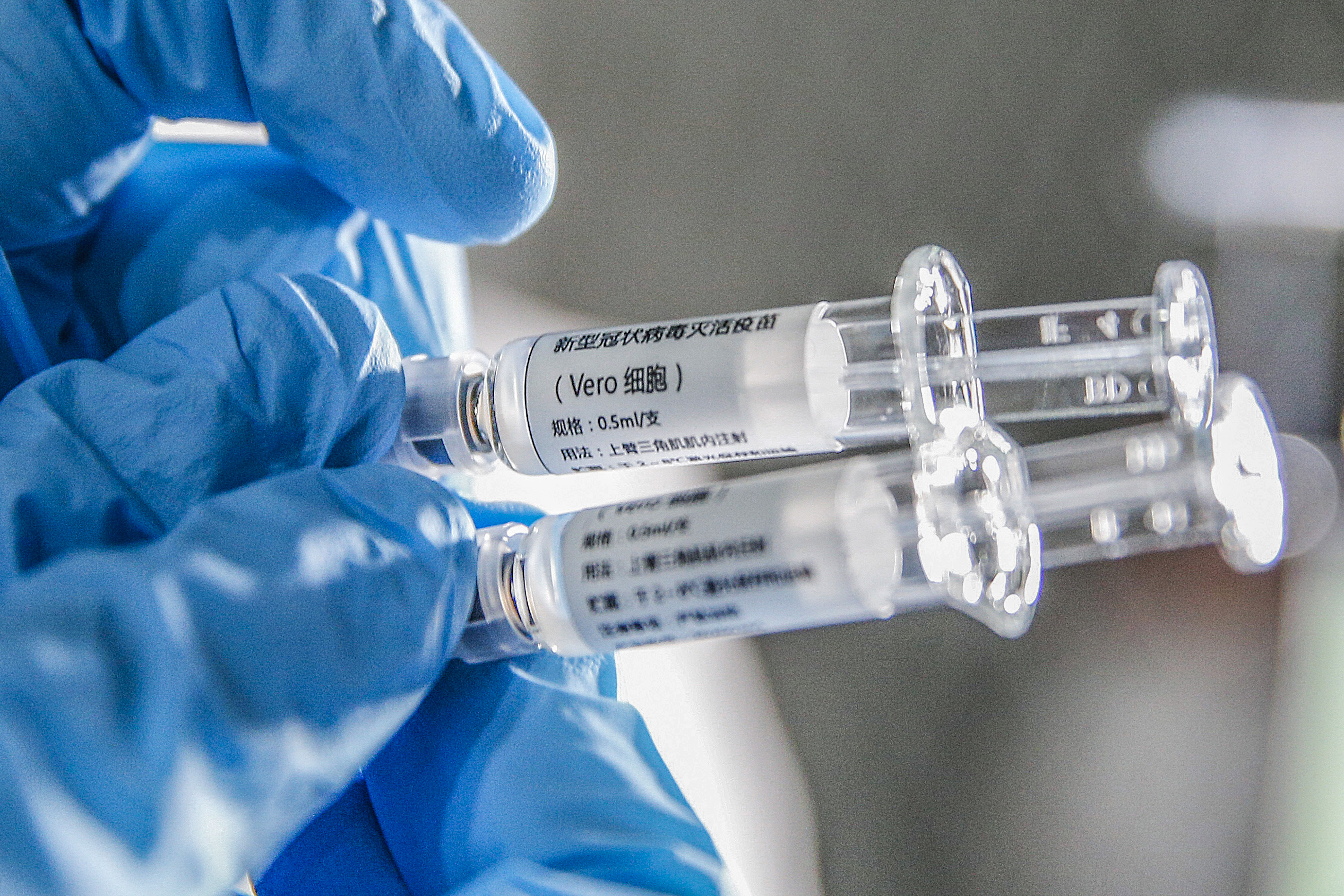

Samples of the COVID-19 inactivated vaccine at Sinovac Biotech Ltd., in Beijing, capital of China, March 16, 2020. /Xinhua

Samples of the COVID-19 inactivated vaccine at Sinovac Biotech Ltd., in Beijing, capital of China, March 16, 2020. /Xinhua

If distribution of a vaccine is left to the market, there will be an even more intense bidding war. Without some kind of allocation mechanism, demand would initially far outstrip supply, and the price would skyrocket. Moreover, while supply eventually would increase and price pressures would ease, there would still be problems. If export restrictions persisted, the high-cost production facilities now being built would divert precious resources from programs to help the poor. And because these facilities remain under construction, they won't add any productive capacity during the period of acute price increases, just when it is needed most.

In the long run, the completion of these facilities would mean that more efficient producers in advanced economies could not resume the same level of sales to poorer countries. Those countries would have their own less-efficient medical supply industries, exporting countries would be left with excess capacity, and everyone would be worse off.

Avoiding such a wasteful outcome requires a mechanism for rationing scarce medical equipment until supplies have increased. Rich countries should not simply extend cash or loans to poorer countries to purchase what they need, because they will effectively be financing a bidding war against themselves. Instead of money, countries that need medical supplies and equipment should receive goods in kind.

The international community, for its part, will need to agree on the criteria for allocating medical supplies, and then enforce them to prevent black markets from developing. Obviously, infection rates and public-health capacity (or the lack thereof) should be the major factors guiding allocation decisions. But recipient countries also will need to agree to refrain from wasting scarce resources on building their own productive capacity.

Given that it already has most of the necessary data, the World Health Organization should take the lead on coordinating medical-supply allocation. In an ideal world, everyone would receive the supplies they need without regard to their ability to pay. In the real world, vaccine developers and PPE producers must be able to count on some reward for their efforts, or they won't undertake them in the first place.

With an allocation mechanism, at least such rewards would not be supercharged by a bidding war. More important, governments in developing and emerging-market countries would be better positioned to resist protectionist pressures, and to expend their scarce resources on programs to ameliorate the pandemic and recession. If these governments have a voice at the table, the road to recovery will be much smoother, and the global production of medical supplies will be more efficient and equitable both now and over the long term.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2020.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)