Editor's note: Wamika Kapur is an Indian Ph.D. scholar of international relations at South Korea's Yonsei University. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

India's government has gone digital with the Sino-India clash by banning 59 mobile apps of Chinese origin. The apps are deemed "prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defense of India, the security of the state and public order" "by elements hostile to national security and defense of India". According to the Indian government, it is to ensure data security of 130 crore Indians against unauthorized transmission of user data to servers outside India. The press release doesn't mention China or the hidden objective of causing economic damage. This ban highlights larger trends of using public policy for political ends and rising techno-nationalism in India.

Tik Tok enjoys huge popularity in India, 200 million users, and its ban is estimated to cause a loss of approximately 6 billion U.S. dollars. ByteDance, the parent company of Tik Tok, had planned to invest 1 billion U.S. dollars in India and employs approximately 2,000 locals. The app is a source of livelihood for many users from divergent socioeconomic backgrounds.

Tik Tok also has a large revenue base in U.S. and China, and the sharp end of the economic consequences of the ban will be felt more deeply in India, which is currently struggling to deal with the impact of COVID-19. Further, it will hurt India's ambition to become a new landscape for economic development. India's political climate does not make it conducive to consumer interests and market competition.

The anti-China sentiment in India has been on an all-time high, and the ban comes right after the recent fatal Sino-India military clashes in the Galwan Valley. The premise of national security is flimsy, and the official statement offers nothing concrete to substantiate these claims.

A more believable version of events would be that the ban is meant to assuage national sentiment. Prime Minister Modi has taken Donald Trump's playbook of using metus hostilis, fear of the enemy, to distract from domestic issues like high levels of unemployment and COVID-19 related deaths by stoking nationalist fervor. However, banning entertainment apps while the country is on lockdown might prove to be counterproductive to that purpose.

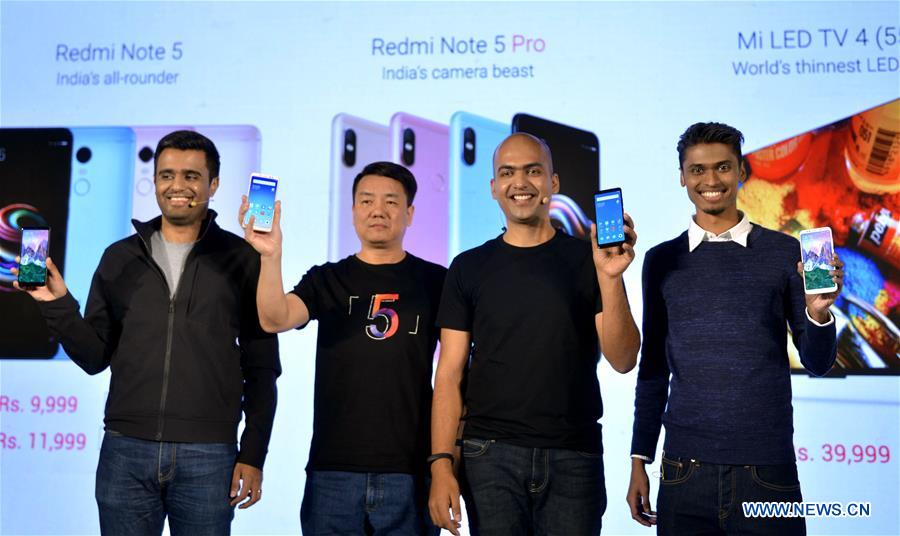

L-R: Xiaomi India product lead Jai Mani, Xiaomi co-founder and vice president Wang Chuan, Xiaomi India Managing Director Manu Jain and Xiaomi India global Vice President and Product Manager Sudeep Sahu at a Xiaomi smartphone promotion event in New Delhi, India, February 14, 2018. /Xinhua

L-R: Xiaomi India product lead Jai Mani, Xiaomi co-founder and vice president Wang Chuan, Xiaomi India Managing Director Manu Jain and Xiaomi India global Vice President and Product Manager Sudeep Sahu at a Xiaomi smartphone promotion event in New Delhi, India, February 14, 2018. /Xinhua

Further, the ban clubs all 59 apps together without specifying which app is causing a data privacy concern. All the apps are of Chinese origin, it can come across as a discriminatory attack which would be against the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules on trade practices. India is ready to defend its ban using the national security exception.

Ironically, China, which places a high priority on national security, in its 2019 proposal on WTO reform called for WTO members "to act in good faith and exercise restraint in invoking provisions on national security exceptions." Even if China chooses to pursue this issue at the WTO, the functioning of the Appellate body is currently paralyzed due to the refusal of America to move towards appointing its members.

India's digital policies are highly protectionist and come under the tag of "digital sovereignty". The same can be seen in India's data localization policies i.e., Personal Data Protection Bill with conditional data transfer. Digital nationalism in India has two aims - encouragement of innovation and promoting government policies. While data nationalism may prevent foreign governments from causing social turmoil, there is a concern that it can make citizens vulnerable to digital authoritarianism by domestic governments.

Tik Tok had been a sore issue for the Indian government even before it became a security issue. The main concern has been the posting of political content, which was claimed to be anti-national, inciting religious violence, and against Indian moral values. In India, content censoring, apart from being restrictive of freedom of speech and expression, is a very vague field where censorship is applied on a case-by-case basis. This ambiguity can be used by the political party in power to meet political ends. Banning Chinese apps has become a trend for political bargaining during border disputes and was last seen during the 2017 Dokhlam standoff when Indian troops were asked to delete 42 applications.

The ban is a temporary feel-good measure to contain the hyper-nationalist anti-China sentiment building in India. It is highly likely that after meetings with the India teams of the apps, on data policies, the decision would be reversed.

India has been increasingly using economic maneuvers to attempt to strong-arm China diplomatically. This was last seen in India's decision to block the automatic route for foreign direct investments. While these moves may have short term domestic benefits, it could impact India's credibility internationally.

Further, PM Modi set up the "PM Cares Fund" in March to attract donations to fight COVID-19. The fund has received donations from Tik Tok (30 crores), Xiaomi (10 crores), Huawei (7 crores), One Plus (1 Crore), and Oppo (1 crore). Considering the current economic situation, it would be beneficial for India to diplomatically resolve these issues and focus on development and self-reliance.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)