In front of a grocery store on Beijing's outskirts, several elderly people – all wearing masks – line up, peering at their phones.

There are no big discounts, and they're not waiting to get the newest high-tech products. But until they show the store staff their "health code," they can't do their shopping.

For these over-60s, it's not a simple task. Some cannot locate the mobile application, others simply don't have a smartphone able to scan the QR code needed to download it.

Elderly people stand outside a grocery store in Fangzhuang, Beijing. /Beijing Daily

Elderly people stand outside a grocery store in Fangzhuang, Beijing. /Beijing Daily

In the global fight against the deadly coronavirus, China is employing the latest technology to determine the close contacts of infected people and curb further spread. But it seems, not everyone is easily included.

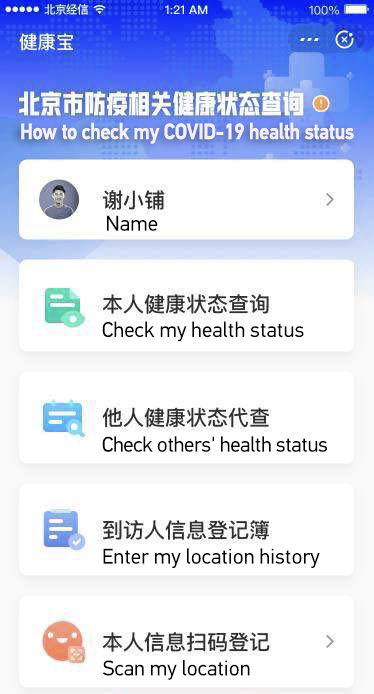

Relying on mobile technology and big data, Chinese authorities introduced a color-based "health code" system – produced by Ant Financial, a fintech firm owned by e-commerce titan Alibaba – in February to detect potential contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases.

A simple click on a mobile application automatically generates colored response codes, in green, yellow and red – each indicating the person's health status over the past 24 hours.

China's "health code" system, translated by CGTN.

China's "health code" system, translated by CGTN.

"Instead of filling in health report forms, residents can now show the codes at community or expressway checkpoints," China's official Xinhua News Agency noted when referring to the service.

The app has been available as a mini program via both WeChat and Alipay, China's No. 1 instant-messaging app and No. 1 online payment platform respectively, since authorities greenlit a gradual return to work in March.

COVID-19 has since been largely under control across the country, with cities and provinces carefully rolling back their lockdown measures.

And to help contain further outbreaks, the "health codes" are now part of daily life. In cafes, hotels, shopping malls and even when buying train or plane tickets, people are only allowed to proceed if their code is green.

Official government data reveals that as of June 25, there had been over 29 million signups for the health code app in Beijing alone. That's about 134 percent of the city's official population.

Yet while the service is convenient for many people, some others, including the elderly and young kids, have been left behind.

"Please help me. I really don't know how the code works. I don't even know what's going on," an elderly person implored outside one grocery store, Beijing Daily reported.

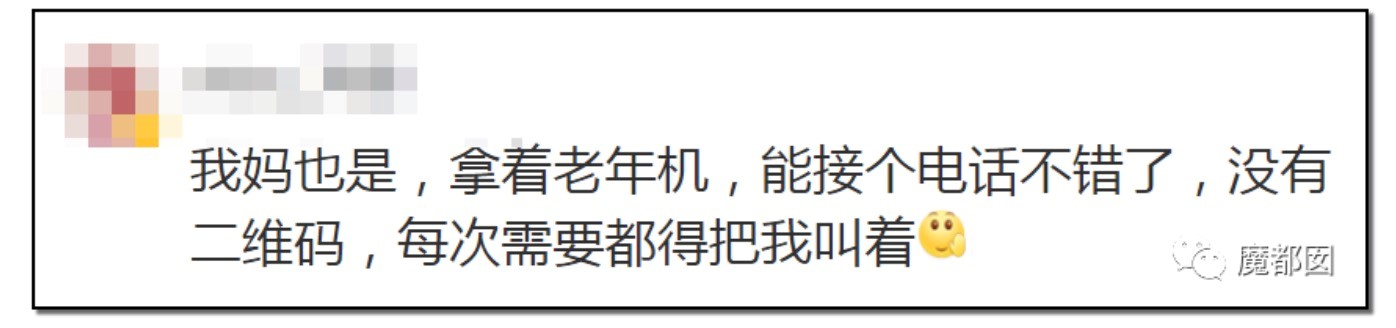

Similar concerns were expressed online, as users worried about their relatives.

"My mom, too, with her dumb phone. The best she can do is answering phone calls," read one comment on Weibo, China's Twitter-like microblog platform.

Screenshot from Weibo, China's Twitter-like microblog platform

Screenshot from Weibo, China's Twitter-like microblog platform

According to the Beijing's official release, starting from June 24, the health code now allows those who cannot get access to the service to check it on others' smartphones.

"In the March version, the function is already allowed," the release said. "One can check the health condition of another person by entering their name, ID number and passing a facial match check."

Privacy concerns about the service have also been raised, with some critical of the need to hand over data and questioning the security of the information released.

A Beijing official insisted that data collection via the app is solely for the purpose of pandemic control. "After 24 hours, the database will expire automatically. We are automatizing the information protection process," said Pan Feng, deputy director of the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Economy and Information Technology, in a press conference in March.

"We are minimizing the data collecting process and (protecting residents') privacy."