01:28

Editor's note: This is the 90th article in the COVID-19 Global Roundup series. Here is the previous one.

Melbourne, Australia's second-largest city, went back into lockdown at midnight on Wednesday, forcing five million Australians to stay home for all but essential business for the next six weeks to contain a flare-up of coronavirus cases.

Cafes, bars, restaurants, and gyms, which only recently reopened, had to shut again. Gatherings are restricted to two people, or the members of your household and visitors to your home are not allowed. State police were patrolling the city and setting up checkpoints on major roads to stop people heading out to regional areas and spreading the virus from what is now Australia's pandemic epicenter, with 860 active cases.

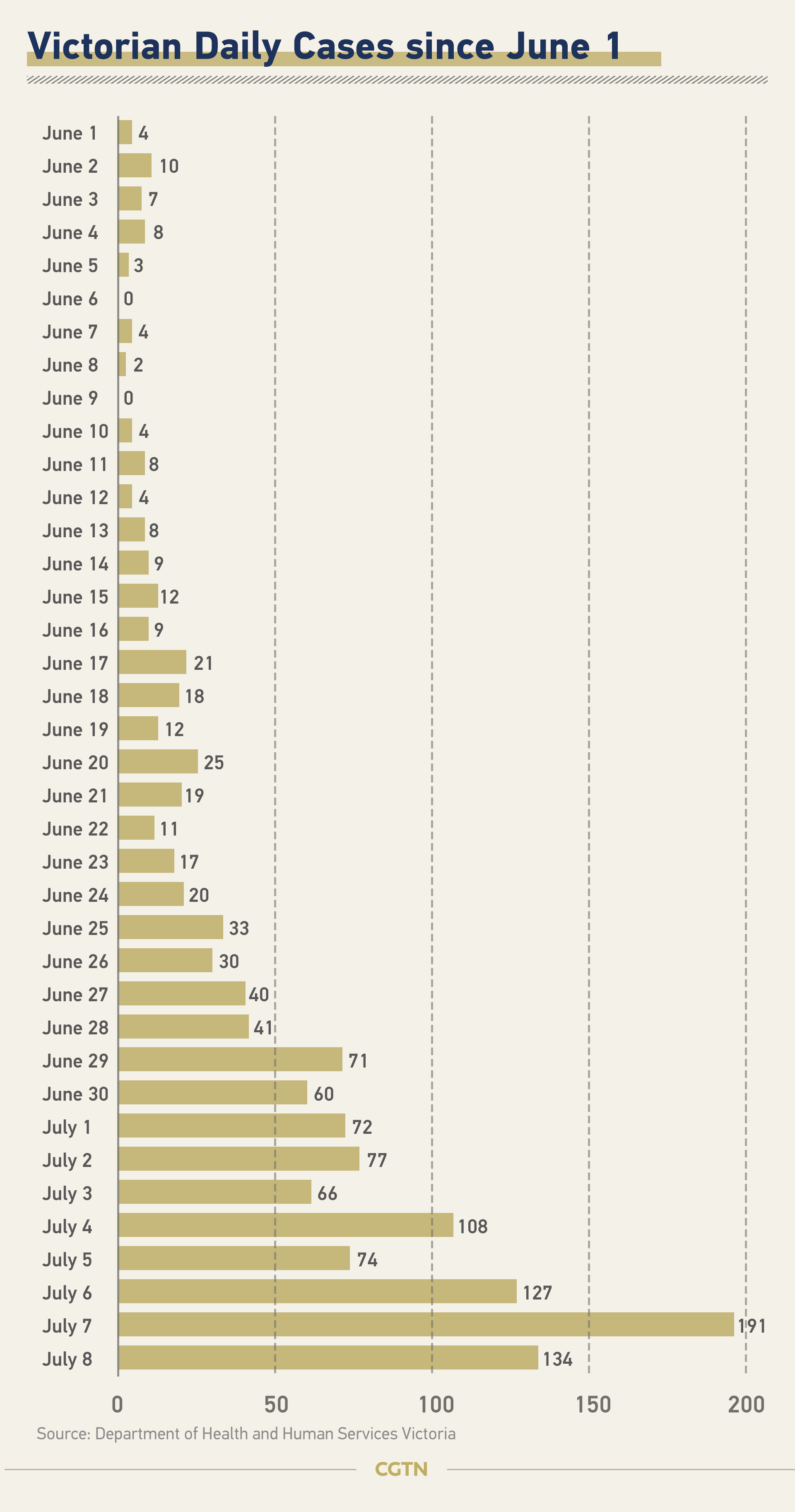

Melbourne, the capital of Victoria state, reported 134 new infections on Wednesday, down from the previous day's record 191 but well over the low single-digit daily increases elsewhere in the country. The renewed lockdown follows the closure of Australia's busiest state border, between Victoria and the most populous state New South Wales(NSW), on Tuesday night, the first such closure since the 1919 Spanish Flu pandemic.

In Sydney, authorities were scrambling to track down 48 passengers who were allowed to disembark a flight from Melbourne overnight without being checked for COVID-19 symptoms. Other states and territories are barring Victorian residents from entering to preserve their hard-won gains against the virus.

Fears of a broader second wave were mounting.

What has lead to the recent surge of coronavirus cases in the country, which has been one of the standout performers globally in limiting the spread of the virus? The Victorian Government has begun an inquiry into how the virus managed to regather momentum around the city, which will last for eight to ten weeks.

Hidden peril: Public housing towers

The recent flare-up in Victoria is concentrated in Melbourne's poorer and more multicultural suburbs, where residents live in cramped conditions.

Among the new COVID-19 cases in Melbourne on Wednesday were 75 occupants of nine public housing towers in Flemington and North Melbourne. Authorities have placed the nine buildings into complete lockdown at the weekend, barring some 3,000 residents from leaving for five days and racing to test everyone in the towers.

As part of gentrification in Australia, governments began to built public housing towers after WWII, and many in Victoria were finished between 1962 and 1976 to clear cramped and often unsewered slums, replacing them with well-appointed apartments. In the 1960s, tenants in these buildings came not only from Australia but from northern and southern Europe, including Britain, Greece, Italy, and the former Yugoslavia. Ten years later, Turkish migrants formed the major residents, and then after 1975, refugees from Vietnam, Timor-Leste, and South America flooded in.

From the 1990s, residents in the public buildings changed again, mainly refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina, the former USSR and the Baltic states, and from the Horn of Africa – Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea – along with Sudan. About half of these African migrants live in Melbourne.

Public housing towers in Flemington were locked down by local government in Melbourne, Australia, July 6, 2020. /VCG

Public housing towers in Flemington were locked down by local government in Melbourne, Australia, July 6, 2020. /VCG

Families with about six kids living in three-bedroom apartments in these buildings are mostly socially disadvantaged. These families maintained close neighbor ties, with children running between stairwells and knocking on each other's door to call on friends.

Many residents surrounding the buildings hold stereotypes against people living there. After the coronavirus outbreak, outsiders' views towards these buildings became even more negative. A broadcaster this week called the buildings "multi-story monstrosities."

Acting Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly told reporters that diseases tend to spread through disadvantaged communities mainly because they are more crowded, and the lockdown measures were necessary to stop the virus spreading.

Griffith University Professor Nigel McMillan criticized that Sydney has the same sort of public housing and the same multicultural makeup, but the city doesn't see the same problem. He believes the Victorian government has done something wrong.

There has been criticism of the Victorian government's efforts to inform vulnerable and linguistically diverse communities about the pandemic.

State police set up checkpoints on major roads to stop people heading out to regional areas. /VCG

State police set up checkpoints on major roads to stop people heading out to regional areas. /VCG

Quarantine hotel scandals

In addition to public housing buildings, many of the recent infections can also be traced directly back to quarantine hotels, which are believed to lead to returnees spreading the virus. According to The Australian, 31 cases, including security guards and returnees, are from the 5-star Stamford Plaza Melbourne, and that number continues to grow.

Authorities now are investigating alleged security lapses at Melbourne hotels used to quarantine overseas arrivals after local media outlets reported that guards slept with guests during quarantine, that these securities personnel have less training about infection control and that quarantined families were allowed to go between rooms to play cards and games.

Unlike most states and territories that deployed police forces or troops to regulate the quarantine, the Victorian government contracted out the task to private security firm MSS and two other firms without any formal tender process, and it also confirmed that some security work was outsourced to other security companies.

Critics pointed out in NSW isolation hotels, where the state government deployed the Australian Defense Force (ADF) personnel to run, no workers have tested positive to COVID-19.

Supermarket shelves with fruit, vegetable and frozen meat were snapped up after the reimposed lockdown, Melbourne, Australia, July 8, 2020. /VCG

Supermarket shelves with fruit, vegetable and frozen meat were snapped up after the reimposed lockdown, Melbourne, Australia, July 8, 2020. /VCG

According to The AGE, a local newspaper based in Victoria, security staff regularly shifted between different sites and only got informed by phone message the night before. A guard told the newspaper that some subcontractors treated safety protocols with contempt, adding most of them barely pay attention to nurses who taught them how to use masks properly.

Another news outlet reported that these guards were only offered "five minutes" of training before they started their job. An official from the United Workers Union criticized that using private security firms makes these companies view it just as a "money-making" exercise, which led to cost-cutting phenomenon such as less medical training and using subcontractors who work at multiple sites at the same time.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews has been keeping silent on the public concern: Why his government didn't use troops or police to help run quarantine hotels, saying he is waiting for the result of the investigation and he will not shirk his responsibility.

"The best thing in my judgment is to focus on the things you can control, and none of us can go back and change any of that," he told reporters.

(With input from agencies)