When a mysterious new virus began spreading across the world in the 1980s, reaching South Africa during the latter throes of its cruel apartheid regime, failures in governance, misinformation and stigma attached to those infected were rife. Initially, little was known about the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and its link to the potentially fatal Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). The virus' spread continued well into South Africa's post-apartheid era from 1994 onward, and the country now bears the highest AIDS burden in the world with 7.7 million HIV positive in 2018, according to UNAIDS.

While progress has been made in managing South Africa's AIDS crisis, the systems in place were gravely threatened when COVID-19, another previously unknown zoonotic disease borne from a virus – and followed by a similar cloud of panic – hit the country earlier this year.

Prioritizing one pandemic over another

South Africa is yet to reach its peak in coronavirus infections. A strict lockdown imposed in late March bought hospitals time to prepare for the influx of cases though restrictions were eased on June 1 to lessen the economic damage caused by widespread closures. South Africans' newfound freedom has caused the national infection curve to rise sharply: The country now has 238,339 confirmed cases and 3,720 deaths according to government figures – making it the most affected country on the African continent – in a population of nearly 60 million.

The lockdown made those reliant on HIV/AIDS support even more vulnerable.

A mural urging people to stay at home in Soweto, South Africa, June 19, 2020. /AP

A mural urging people to stay at home in Soweto, South Africa, June 19, 2020. /AP

"It has devastated the program," Professor Francois Venter, deputy executive director of Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute in Johannesburg, told CGTN. "We are hearing of people too scared, for reasons of getting COVID, to police arresting them or being forcibly quarantined, to get their tablets. We have also seen plummeting testing for HIV."

The fear Venter describes affects a large section of the population; in South Africa nearly one in five people between the ages of 15 to 49 are HIV positive. But, they may not be in the most danger. According to research by the Western Cape Government released in early June, those with HIV are more likely to die from COVID-19 by a factor of 2.75, though this ratio is far lower than other risk factors such as age and diabetes.

Certain antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) and oxygen are out of stock in some areas, according to Lauren Jankelwitz, CEO of the South African HIV Clinicians Society. There is no cure or vaccine for AIDS, and many are dependent on ARVs to survive. "The medicine shortages are of particular concern as many people will die," she said.

Nonetheless, the U.S.' immunology chief Anthony Fauci, speaking on Monday at the AIDS 2020 conference which is being held remotely this week, assured that "there is no doubt there is no diversion of resources that are AIDS resources, AIDS dollars." In fact, the situation could ultimately benefit the pre-existing HIV/AIDS pandemic, as "there are so many resources because of the emergent nature of COVID-19, that in some respects there's COVID-19 dollars that are being put into situations that might ultimately, in the long run, benefit HIV/AIDS."

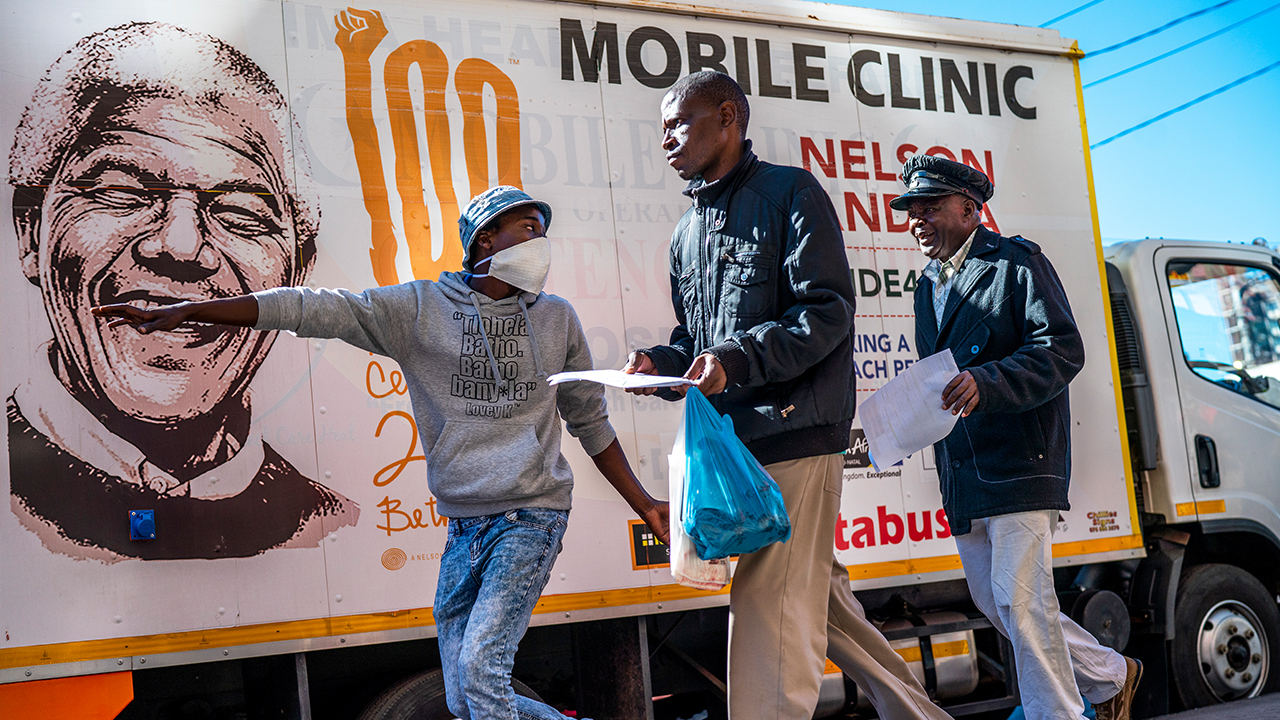

A volunteer directs two men towards a medical tent where they will be tested for COVID-19 as well as HIV and tuberculosis in downtown Johannesburg, South Africa, April 30, 2020. /AP

A volunteer directs two men towards a medical tent where they will be tested for COVID-19 as well as HIV and tuberculosis in downtown Johannesburg, South Africa, April 30, 2020. /AP

A report released Monday by the UN's AIDS agency told a different story, however, saying that the coronavirus pandemic risked setting back progress made in fighting HIV/AIDS by a decade or more.

"COVID-19 is a disease that is claiming resources – the labs, the scientists, the health workers – from HIV work... One disease can't be used to fight another," said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS' executive director at the report's launch in Geneva, Switzerland.

Prepared for the fight, up to a point

South Africa's response to the arrival of the novel coronavirus drew on its existing HIV/AIDS infrastructure. The country is one accustomed to the spread of disease: Tuberculosis – in fact the leading cause of death in South Africans' with HIV/AIDS – and listeria are also common.

Systems that could help prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus were already in place, such as differentiated service delivery to reduce congestion at health facilities, mobile clinics, multi-month drug dispensing and self-testing. But, the "problem is this isn't necessarily countrywide," Linda-Gail Bekker, deputy director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre located in Cape Town, told CGTN. "The better resourced provinces have been more effective in getting this going, (such as) Western Cape. It is less well developed in provinces where the health systems are less robust, (like) Eastern Cape."

Heath officials check a list of people who are to be tested for COVID-19, HIV and tuberculosis in Johannesburg, South Africa, April 30, 2020. /AP

Heath officials check a list of people who are to be tested for COVID-19, HIV and tuberculosis in Johannesburg, South Africa, April 30, 2020. /AP

South Africa also has a significant disease and immunology knowledge base, though the newness of the coronavirus crisis has proved a stumbling block. "All the infectious diseases specialists that are instrumental in the work within the HIV sector are involved in advising the health minister. Unfortunately, a lot isn't based on evidence and they are working a little blind, so the minister doesn't always listen to the advice," Jankelwitz of the South African HIV Clinicians Society detailed.

The South African government has also tripped up elsewhere. Only products on a list of essential goods were available for sale during the national lockdown, and confusion over what made the cut meant that some pharmacies prohibited the sale of condoms, a common means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases. The Department of Health confirmed in late April that condoms were indeed such essential goods.

The risk of siphoning resources away from South Africa's HIV/AIDS fight is large. Around 42,500 more lives than normal would be lost to the disease in the next year if half the people in South Africa on treatment were unable to get their drugs for six months, a number that could rise to 112,000 excess deaths should ARV supplies collapse completely, according to a modelling study conducted by the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS and reported by South African news platform Business Live.

"Paying single-minded attention to COVID without mitigating the effects on the rest of the health care system means that we will be picking up a health disaster for years to come," Venter of Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute warned.