Editor's note: Josef Gregory Mahoney is a professor of politics at East China Normal University. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

History tells us that the first person to refer to a country as a "sick man" was Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. He pronounced those words in a conversation with a British envoy in 1853. Describing the Ottoman Empire "gravely ill," the Russian monarch concluded an Ottoman collapse would be a "great misfortune and destabilizing."

These proved prescient concerns, insomuch as Ottoman weaknesses contributed to conflict between Russia and the UK in the Crimean War, and later, a major factor leading to World War I.

A certain irony has long been clear. While the Ottomans were burdened by an ancien régime incapable of addressing its own growing systemic problems or competing effectively against rising powers, the same was true for Russia.

Indeed, the rule of Nicholas I is described as disastrous, and his three successors, two of whom were assassinated, generally made bad things worse, including his namesake, Nicholas II, who's tragic endpoint marked the end of the line.

Nevertheless, as it became somewhat commonplace to refer to the Ottoman Empire as the "the sick man of Europe," the term was also applied to the late-Qing Dynasty as "the sick man of Asia."

Given that Ottoman power was centered in today's Turkey, historically described in the West as "Asia Minor" and the Orient or Near East, concerns that the term in some way intersects with the pejorative cultural milieu described by Edward Said as "Orientalism" have long been valid. These concerns resurfaced earlier this year during the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak following the publishing of a controversial op-ed in The Wall Street Journal titled "China is the real sick man of Asia."

In the uproar that followed, including China's expulsion of three WSJ reporters, the journal's editorial board acknowledged the term was insensitive but shifted blame to China: "The truth is that Beijing's rulers are punishing our reporters so they can change the subject from the Chinese public's anger about the government's management of the coronavirus scourge ..."

Of course, there are two problems with this response. First, it essentially justifies using what many take as a historical and racially insensitive term. Second, it is a premature if not misrepresentative and absolutely ironic description of Chinese anger related to Beijing's relatively superior management of the outbreak. Consequently, one is hard pressed to find Chinese anger with Beijing on par with American anger with Washington.

Police deliver groceries to Kirkland Fire Station 21 where firefighters are in quarantine following their response to coronavirus cases in Kirkland, Washington, U.S., March 2, 2020. /Reuters

Police deliver groceries to Kirkland Fire Station 21 where firefighters are in quarantine following their response to coronavirus cases in Kirkland, Washington, U.S., March 2, 2020. /Reuters

'Insensitive' is putting it mildly

In China's case, the "sick man" was first used to describe the Qing Dynasty in 1863, and it was even popularized among Western-influenced Chinese intellectuals, most notably Yan Fu, who translated the term literally, bingfu, finding currency with Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao.

Liang was the first to associate the term with China's struggle against opium addiction at the time, and without a doubt the idea proved inspirational for Lu Xun, who famously abandoned his formal medical training to address China's "sickness" with literature, with one very vivid example found in his short story "Medicine" (1919).

While the "sick man" is arguably one of Lu's major tropes, by the turn of the century the term itself was already becoming unpopular among those who had embraced it, in large measure because Westerners frequently mixed it with racist and colonial discourses and imperialist practices.

Who's sick now?

Not only the Ottomans and the Chinese were called sick, the term was used to describe other "eastern" societies, including those of Morocco and Persia in the 19th century and the Philippines in the early 2010s. It also resurfaced, but with a sort of dark civilizational implication – as in you've become as bad as the Ottomans or the Chinese – to describe the UK in the late 1970s and Germany in the 1990s.

But the irony of the WSJ's usage of course is felt most acutely today in the U.S. given the compounding failures of governance related to the outbreak. In fact, while it's equally insensitive to refer to the U.S. as the "sick man," particularly in the throes of a crisis, others have used the term over the past several years to describe the U.S. in contexts unrelated to COVID-19.

For example, in a Bloomberg op-ed in 2017, the U.S. was described as "the sick man of the developed world" for its relatively poor living standards. And while the Washington-based Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) didn't use the term "sick man," a widely-read paper it published last week described the problem of growing inequality in the U.S. as one of its most entrenched and worse than China's.

In fact, the CFR paper was based on data before the outbreak started, and every sober assessment thus far indicates the situation has worsened significantly over the past several months.

In another example, a Foreign Policy op-ed in 2019 led with, "the American empire is the sick man of the 21st century." In that piece, the primary argument centered on Washington's hollowed-out capacity to govern its global empire, a system already historically passé but still a cornerstone of American identity and policymaking.

But of course, the most painfully relevant example for most is today's, with new COVID-19 cases roughly double than what they were in the initial bad days of the outbreak in the U.S., with a White House addicted to misinformation and polarizing politics and reeling in the polls during an election year, with nearly every facet of life in some form of disarray, and with hundreds still dying daily. Thus, "sickness," in the literal and figurative senses of the word, has become an omnipresent American reality.

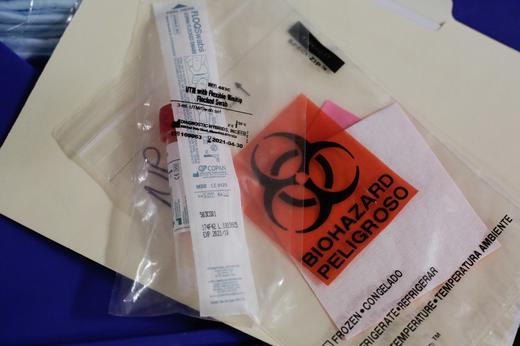

A swab to be used for testing novel coronavirus is seen in the supplies of Harborview Medical Center's home assessment team, Seattle, Washington, U.S., February 29, 2020. /Reuters

A swab to be used for testing novel coronavirus is seen in the supplies of Harborview Medical Center's home assessment team, Seattle, Washington, U.S., February 29, 2020. /Reuters

'Woke' but not awakened

As Lu Xun understood, one of the key challenges facing China in the first two decades of the 20th century was to awaken a critical mass of people to the necessity of change. This is why he turned to writing, and doing so in vernacular, to engage the masses in the destiny of the nation.

Today, in the U.S., a similar problem exists, albeit with what appears to be strikingly different conditions. For example, in the U.S. today, there is no shortage of mass media, no shortage of political discourse, no shortage of discussions in everyday language.

Indeed, the problem is not that people don't realize that problems exist; they're simply unable to reach a consensus on what the problems are, what caused them, who's responsible for fixing them, and of course, how to actually fix them.

Even when clarity on some of these points is reached, rarely does it correspond closely with effective solution-making.

Trump and his supporters, for example, blame China, Latin American migrants, Islamic refugees, supporters of Black Lives Matter, groups opposed to fascism, multilateral organizations like the World Health Organization and United Nations, previous presidential administrations, and even the presence of an oppositional "deep state" despite having more influence and control over the three branches of government, arguably, than any other administration in decades.

If one can't govern effectively with that kind of power, then perhaps one is grossly incapable or the system is broken – or both. Meanwhile, the blame game continues. It's either too much rule of law or too much rule of rules, or the wrong mix of both.

It's a congress failing to effectively legislate, or legislating too much. It's an imperial presidency that sidestepped impeachment despite compelling evidence and even a follow-up book by hardline insider John Bolton confirming that the allegations and worse were true, with reports now turning to John Yoo, who penned the so-called Torture Memos for George W. Bush, as Trump explores ruling by decree.

Or perhaps it's a judicial system that legislates from the bench as some allege, or conversely, limits itself too conservatively to overly narrow, strict interpretations of the U.S. Constitution, which most conclude is now impossible to amend or reform given pervasive polarization.

Unfortunately, unable to create consensus, many choose to create confusion instead.

To be fair, for those familiar with the American history, problems like those described here, even failures to control outbreaks, including those originating in the U.S. as well as blaming others unfairly for disease, are deeply rooted and in some respects similar to previous U.S. experiences, all the way back to the early days of the republic. In some cases, these problems are even intrinsic to the U.S. system. And they aren't unique to the U.S.

A terminal condition or the end of history?

What is unique, however, is the growing record of American failure at home and abroad, which has become starkly apparent to many given the U.S. position as the sole superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In short, the world changed but the U.S. didn't, or didn't enough. The U.S. and its system has become today's ancien régime, and one might reasonably conclude, either stuck in time or trapped in a degenerative time loop, continuously circling back to its so-called "end of history," i.e., roughly the Reagan Era, unable to move beyond it. Meanwhile, others have moved forward and done better than before, including China.

This is why in part so many in Washington today are desperate to blame and demonize China, to drag it and others down, to start Cold War 2.0, to flirt dangerously close even with a hot war. And it's why some have pointed to Trump's failures with COVID-19 as being analogous with Reagan's failures with HIV/AIDS, among other shortcomings.

But the lesson few have yet to learn today is neither bullets nor silver bullets – the latter in the form of a vaccine or a Joe Biden win in November – will prove palliative. Nor will a new Cold War, even though this is the one issue that resonates with Democrats and Republicans.

The sickness runs much deeper, and like a pandemic, threatens everyone more and more, everywhere. Consequently, while we shouldn't call anyone a sick man, we must recognize sickness when we see it and find ways to contain it if a cure is impossible or simply out of reach.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)