Editor's Note: Pan Deng is a member of the Academic Committee at Charhar Institute, executive director of the Latin America Law Center of China University of Political Science and Law and a distinguished professor at the Center for Latin American Studies at Southwest University of Science and Technology. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Last weekend, former Chilean President Lagos published a signed article entitled "Abandon the Trump Model" in La Tercera, a mainstream media in Chile, criticizing the "America First" policy characterized by the U.S. tearing up agreements and retreating from international organizations. He called on Latin American governments to stay strategically sober in their relations with the United States and resist the United States' hegemonic acts in meddling with Latin American affairs.

In the U.S.' global strategy, Latin America has always taken an important and special position. The U.S. has long regarded Latin America as its "backyard," believing that it has unparalleled dominance and influence. Therefore, the U.S. attaches particular importance to the management of its role in the Western Hemisphere.

However, the incumbent administration does not seem to follow the long-standing strategy that Washington adopted toward Latin America in this century. Trump is the only White House occupant among recent U.S. presidents that has not paid a state visit to Latin America during his first term. He also missed the Summits of the Americas in Peru in 2018, becoming the first U.S. president not to attend the summit. Although the presidential race is now in full swing, this administration has not yet promulgated a written strategy toward Latin America. His Latin American allies see such behavior as "contempt from the North."

Meanwhile, the U.S. openly follows the playbook of the notorious "Monroe Doctrine," proposed at the beginning of the last century, and puts much greater pressure on Latin America. On the one hand, it does not allow the political, economic and social order of Latin America to be out of its control in an attempt to protect its own national interests, while on the other hand, it tries to exclude foreign countries, especially China and Russia, from developing friendly and cooperative relations with Latin America to reinforce its hegemony in this region.

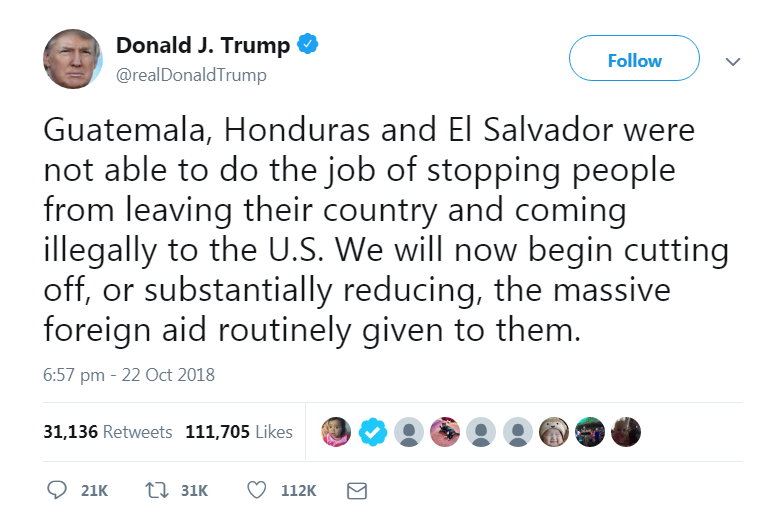

A screenshot of President Trump's October 22, 2018 tweet announcing that the U.S. will cut Central American aid over migrant caravan.

A screenshot of President Trump's October 22, 2018 tweet announcing that the U.S. will cut Central American aid over migrant caravan.

By linking immigration issues with trade policies, tariff barriers and foreign aid, the U.S. forces Latin American countries to strengthen border control and curb the outflow of illegal migrants. It threatens that if Latin American countries fail to solve this problem properly, it will directly close the U.S. border with Mexico.

Last year, the U.S. unilaterally terminated foreign aid programs to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras on the grounds that the three countries' governments were not committed enough to controlling the outflow of migrants. At the worst moment of the pandemic crisis, the U.S. deported Central American migrants, aggravating the heavy toll the virus had on the public health systems of those countries.

In terms of trade policy, the White House first withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) that took half a decade to reach, putting Mexico, Chile and Peru in a very awkward situation. Then, on the pretext of the huge trade deficit with Mexico and the outdated terms of the bilateral agreement, it put pressure on Mexico in all aspects by building border walls, deporting illegal immigrants and imposing tariffs to force Mexico to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement.

This month, the alternative U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) came into effect. The White House claimed that the new agreement will benefit U.S. agriculture, manufacturing and commerce and reverse its mounting trade deficit with Mexico, which is currently at 70 billion U.S. dollars. But Mexico, on the other hand, has become the biggest "loser." The new rules of origin and hourly wage standards alone would severely set back its economy, causing the exodus of foreign capital and shrinking job opportunities. Mexico's risk of capital flight has increased dramatically.

Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaido attends a rally against Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro's government in Caracas, Venezuela, March 9, 2019. /VCG

Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaido attends a rally against Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro's government in Caracas, Venezuela, March 9, 2019. /VCG

The U.S. is very heavy-handed in how it treats countries with different ideologies. First, it openly attaches stigmatizing "labels" to such countries, and then it uses every trick in the book to effect political change, including economic sanctions, military threats and color revolutions. For example, shortly after Trump took office, he terminated the process of normalizing relations with Cuba initiated under Obama's watch.

By creating hype around the "sonic attacks," the Trump administration activated Title III of the Helms-Burton Act to impose multiple sanctions on Cuba, including a travel ban and a reduced remittance quota.

In addition to inciting the opposition to take unconventional measures against the legitimate Venezuelan government, the U.S. also included more than a hundred Venezuelan officials on the sanctions list, publicly pursues senior officials in the name of "corruption" and "drug trafficking" by offering bounties for so-called evidence, and released the "Democratic Transition Framework" which is intended to induce the left to share power with the opposition on the condition of "lifting sanctions."

The U.S. also gave vocal support and financial aid to the opposition in Nicaragua, froze the assets of senior officials and their families in the United States, and used regional organizations to put pressure on the Ortega administration in an attempt to overthrow it.

Although the U.S.' efforts to suppress the leftists and woo the rightists have, to a certain extent, catered to the short-term governing needs of some Latin American countries, its excessive exercise of "hegemony" has also fueled the discontent and contradictions of Latin America toward the United States.

The U.S. has failed to address the unresolved issues of immigration and transnational crime, and its overbearing and domineering policy orientation has caused anger and anguish in countries like Mexico. A Gallup poll showed that after Trump took office, the U.S.'s approval rating among people in 20 Latin American countries dropped by 21 percentage points. Now it rests at only 24 percent. Among them, only 16 percent of Mexican people are happy with the U.S., falling by 28 percentage points. The approval rates of the U.S. in countries such as Haiti and Peru fell to the lowest level in history.

Although few Latin American countries dare to openly act in defiance of the United States, anger among ordinary people is growing. If the U.S. still wants to maintain its leadership in the Western Hemisphere, it's time it reflects on its strategy toward Latin America.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)