After weeks of negotiations, the tense situation raised by the June 15 clash in the Galwan river valley along the China-India border is developing in the direction of easing and cooling.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin Tuesday confirmed that two sides' border troops have disengaged in most localities and the two countries are actively preparing for the fifth round of commander-level talks to resolve outstanding issues on the ground.

Despite the de-escalation of border tension, New Delhi hasn't stopped its "boycott China" campaign, a "but the wind will not subside" flavor. India last month blocked 59 apps developed by Chinese firms and followed it up by banning an additional 47 apps this week.

Apart from the U.S. and Japan, India also plans to invite Australia to this year's Malabar Naval Games. Australia's recent relation with China is also souring over the South China Sea issue and coronavirus inquiry.

What's behind India's anti-China sentiment wave?

The anti-China sentiment in India erupted after the border clash. However, analysts pointed out the wave is rooted in India's changing China policy from before the clash.

Bhim Bhurtel, former executive director of the Nepal South Asia Center, said that India's changing contours of its policy toward China appeared last year after re-elected Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi appointed Subrahmanyam Jaishankar as external affairs minister in May 2019.

Jaishankar was known to be staunchly pro-American and anti-Chinese, said Bhurtel, adding that the minister advocated for a strong partnership with the U.S. and a hawkish China strategy.

With the escalating COVID-19 situation in India, many Indians shifted the blame on China for the outbreak. Kanwal Sibal, India's former foreign secretary, even asked for China to pay a "Wuhan tax."

While Liu Zongyi, secretary-general of the Research Center for China-South Asia Cooperation at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies said that after the border clash, Modi's policy toward China has fallen into a quagmire because of "domestic political struggles and rising Hindu nationalism."

"Party struggles in India are not rational," said Liu, adding that the opposition Indian National Congress (INC) has been exploiting Galwan Valley clash to drag down Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Guided by a narrow objective of winning elections, they (Indian political parties) would even rather see a war between India and China as they don't care about overall diplomatic interests, or anything else, according to Liu.

He added that Modi aimed to take advantage of the prevailing Hindu nationalist sentiment to stabilize his political position when BJP assumed power in 2014. However, the expert believes that Modi has subsequently lost control of it. "He now has no option other than cater to extreme Hindu nationalist positions and accuse China of being expansionist."

Why decoupling from China will hurt India more?

Ritesh Kumar Singh, a former assistant director of the Finance Commission of India, pointed out that India's attempt to decouple from China will only hurt Indian consumers.

"With China often being the most cost effective supplier, that will only jack up the cost of public procurement and extra burden for payers," the now chief economist of Indonomics Consulting said.

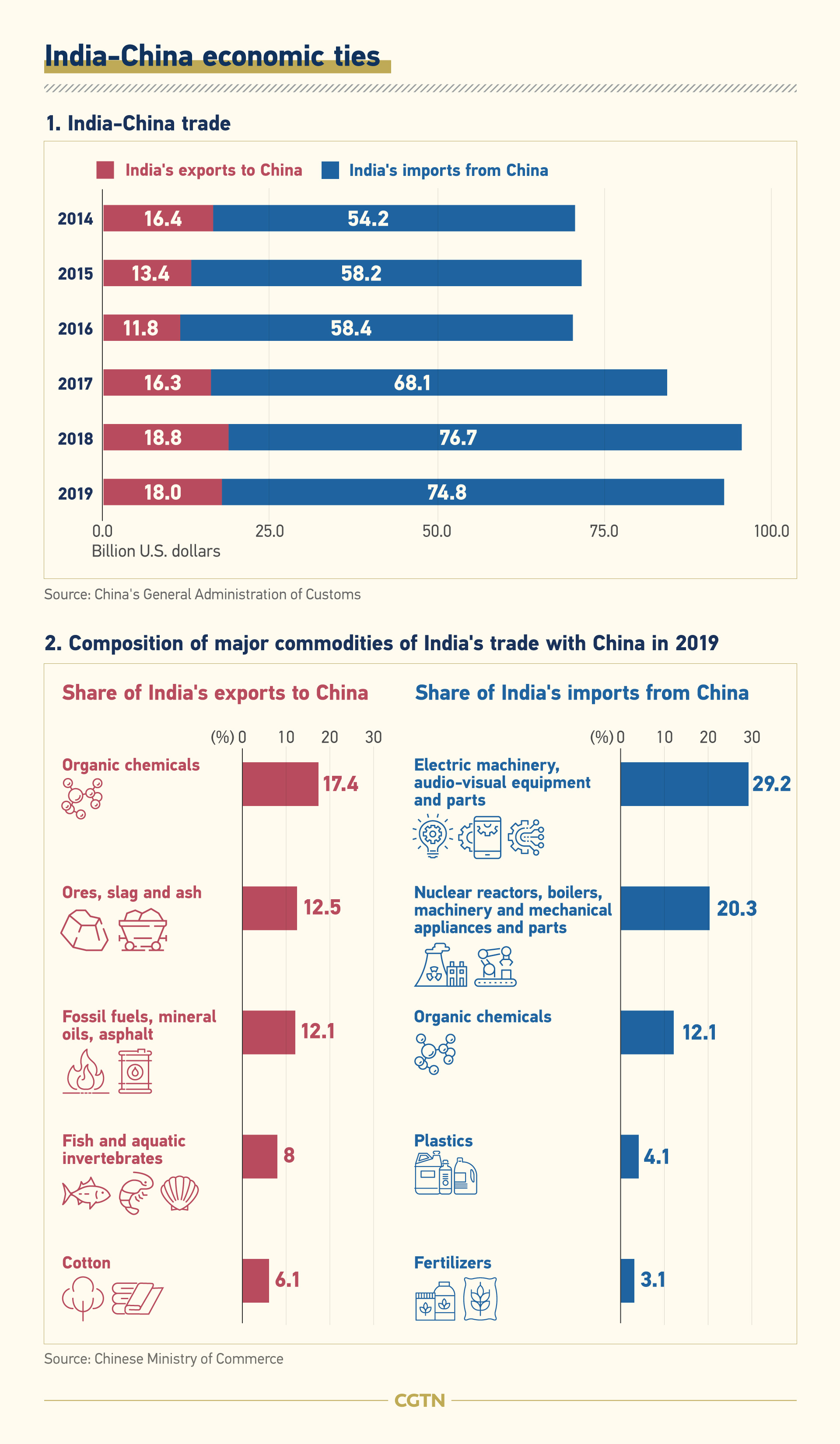

China is India's second-largest trading partner. India's imports from China in 2019 reached 74.8 billion U.S. dollars, out of 92.8 billion two-way trade.

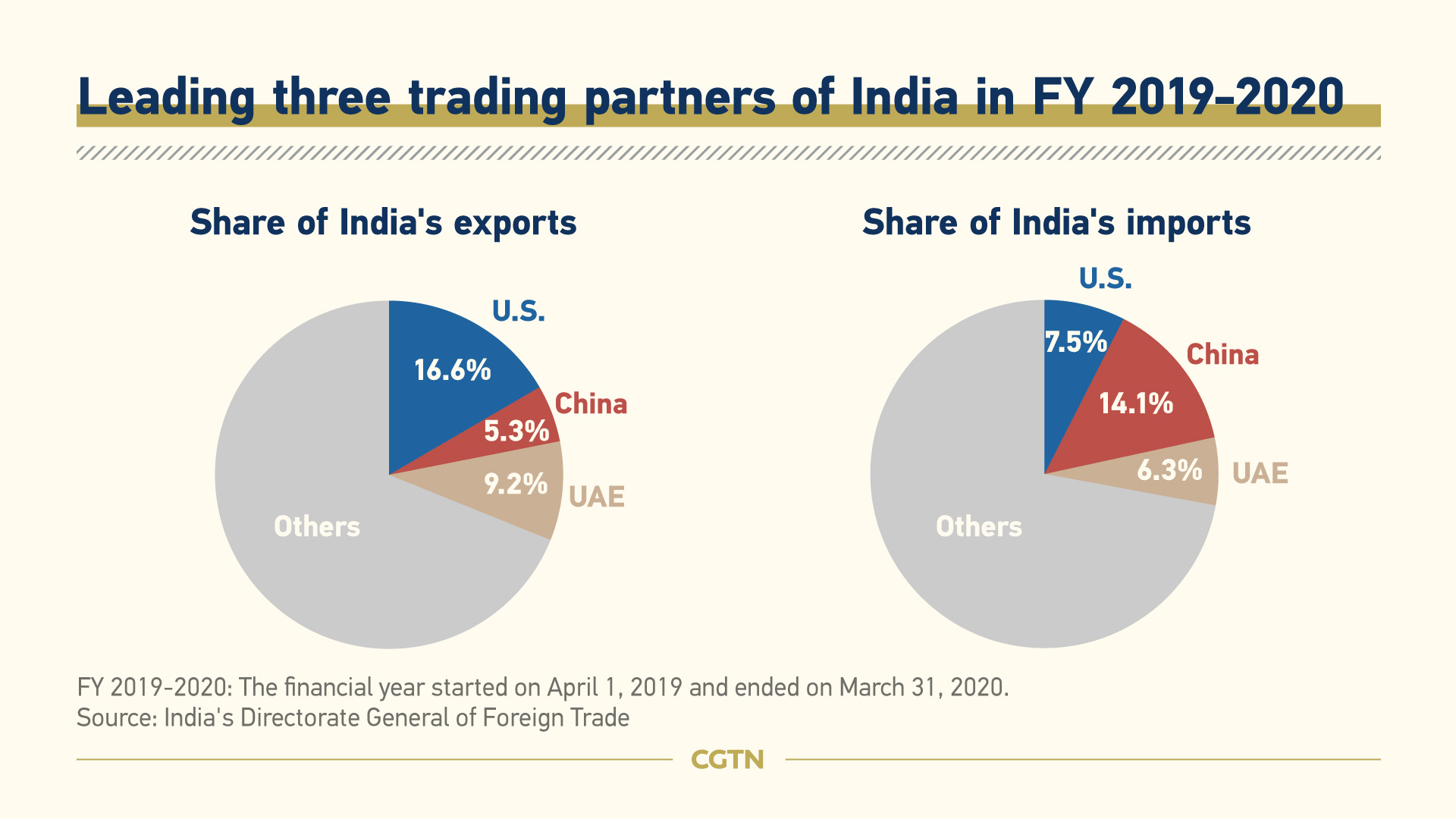

A closer look at the data of the financial year from April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020, shows that banning trade with China means India would lose over 5 percent of its exports and 14.1 of its imports across sectors such as electronics, chemicals and machinery.

Analysts also said that India's poorest consumers would be affected the most as they are most price-sensitive. According to World Bank data, over 20 percent of India's population are still living in poverty, on less than 1.9 dollars a day.

Calling the ban as an "overnight shock", Dev Khare, a partner at the venture firm Lightspeed India, acknowledged that India's app ban was a populist, "feel-good step" in some ways.

As Chinese Foreign Ministry noted banning these apps will not serve the interests of the Indian side, because what's behind these apps are interests of Indian users, enormous local job opportunities and foreign investment.

Military burden

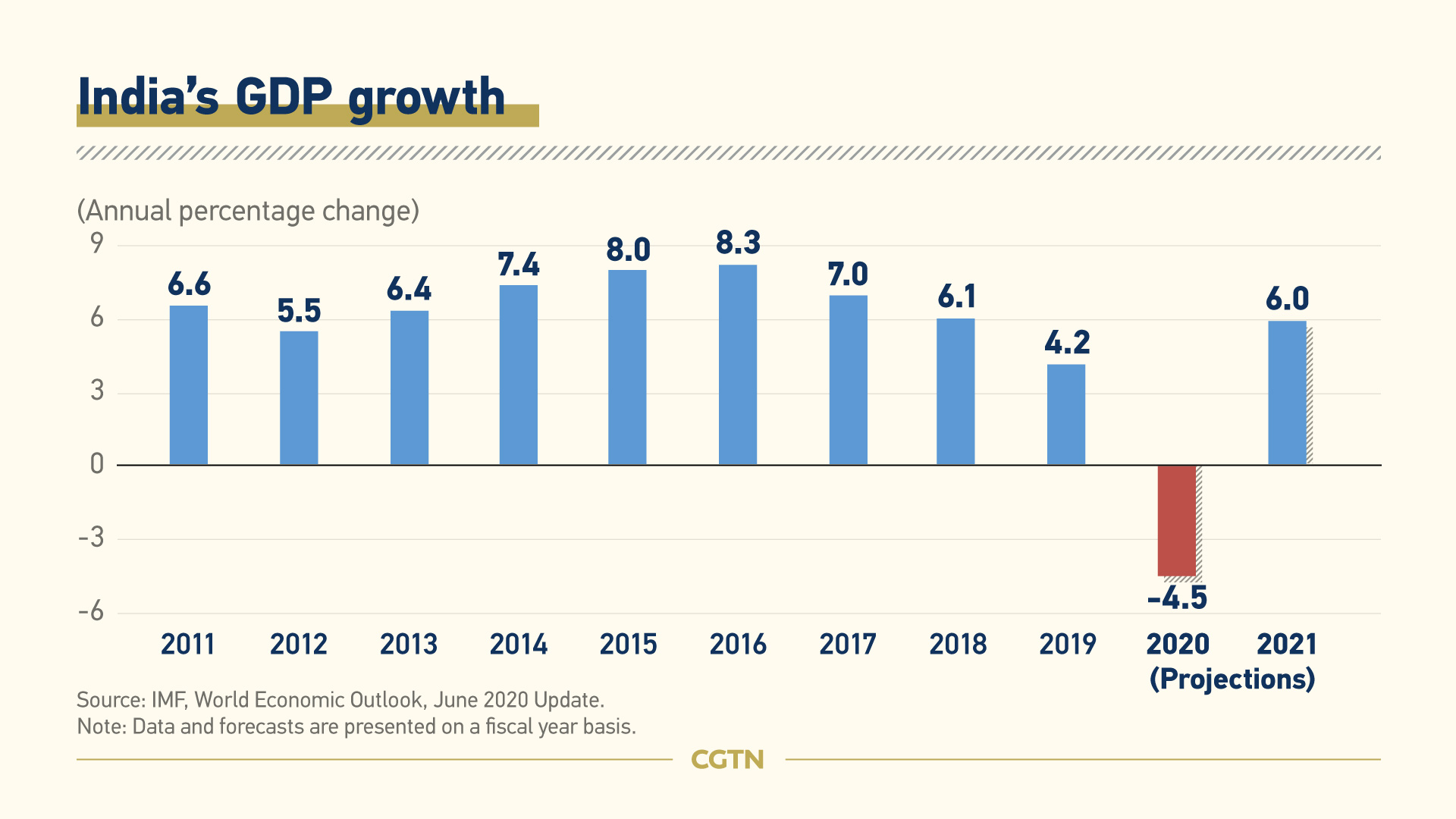

The International Monetary Fund projected India's GDP would contract by 4.5 percent in 2020 but India continues to generously increase military spending.

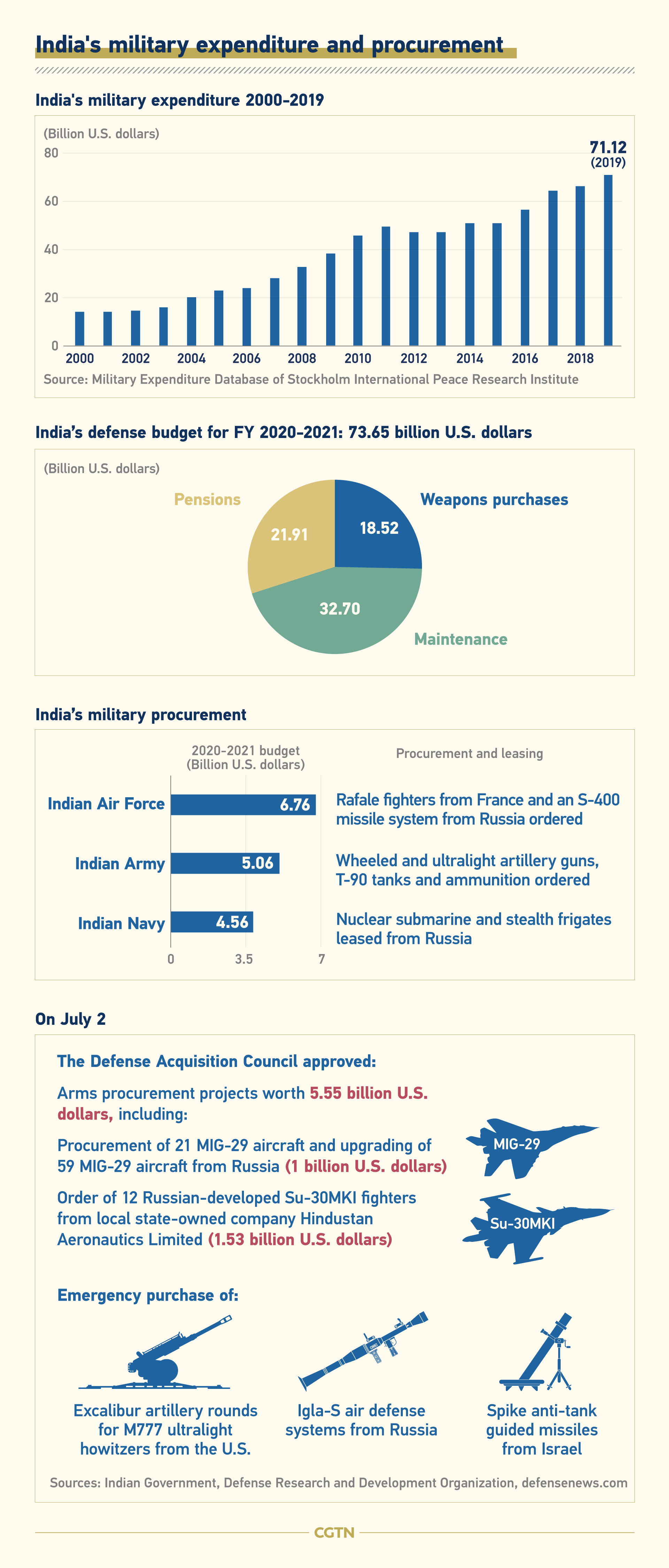

After the border clash, India has accelerated the domestic and foreign purchase of weapons. The Defense Acquisition Council on July 2 approved a collection of arms procurement projects worth 5.55 billion U.S. dollars, nearly one thirds of this year's total weapons purchases budget.

Indian media has reported that New Delhi was likely to deploy more troops in its border with China but local experts warned it could bring fiscal burden to the country.

Noting that more troops mean more payment and infrastructure investment, former army deputy chief of staff Lieutenant General J.P. Singh said more deployment along the border "will impose a recurring expense that will result in an exponential rise in the army's revenue expenditure, severely impacting its long-delayed modernization".

The additional commitment in border would "put further pressure on serviceability, research and development and capital expenditure as revenue cost rise," Laxman Kumar Behera, a senior research fellow at the Delhi based think-tank Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses said.

"It will be painful if the defense budget isn't increased," he added.

(Graphics by Chen Yuyang)