Customers from Harbin shop in a store run by Vietnamese merchant Nguyen Thu Hoai in Dongxing, south China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, December 27, 2019. /Xinhua

Customers from Harbin shop in a store run by Vietnamese merchant Nguyen Thu Hoai in Dongxing, south China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, December 27, 2019. /Xinhua

Editor's note: Ken Moak, who taught economic theory, public policy and globalization at the university level for 33 years, co-authored a book titled "China's Economic Rise and Its Global Impact" in 2015. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

It is not surprising that U.S. State Secretary Mike Pompeo failed to enlist members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in countering China in the South China Sea on a recent trip to the region. This is because Pompeo was, in fact, asking the members to give up their national interests and pay America for doing so. Perhaps members of the club were also aware that territorial claim disputes in the East and South China Seas were created by the U.S. and Japan then blamed China for them.

China is arguably the largest contributor to ASEAN's economic well-being, being the club's biggest trade partner since the COVID-19 pandemic began. In the first quarter of this year, two-way trade between the 10-member organization and China reached 140 billion U.S. dollars, a 6 percent increase year on year. This could explain why ASEAN economies did not contract as deep as those of the West, Japan and elsewhere.

China's importance to ASEAN could increase because other major economies are still struggling to curb the spread of COVID-19 and recovering from the recession caused by the disease. The surge in COVID-19 infections and deaths showed no signs of abating in the major countries forcing them to continue locking down businesses, thus exacerbating their economies. The IMF has predicted economic contraction in the U.S., EU, UK, Japan and India, respectively at 8 percent, 8.2 percent, 8.4 percent, 5.4 percent and 5.6 percent.

These negative growth numbers would suggest ASEAN could not depend on the major economies to help recover from its economic woes. If anything, they might turn inward, becoming populist and protectionist.

In contrast, China registered a positive growth rate of 3.2 percent in the second quarter of this year because the country took decisive measures to control the virus spread shortly after the first cases emerged in early January. Locking down Wuhan and surrounding areas worked, allowing the country to reopen its economy sooner. China could be the only economy that would not sink into a recession in 2020, enabling it to pull the ASEAN and other economies out of the pandemic-induced recession.

Given its history of fulfilling promises, China will most likely follow through with its economic recovery plans of massive spending on infrastructure and increasing private consumption. These projects will require considerable imports of natural resources and food. ASEAN, thanks to proximity and if it remains neutral in the U.S.-China rivalry, stands to benefit the most from China's economic recovery projects.

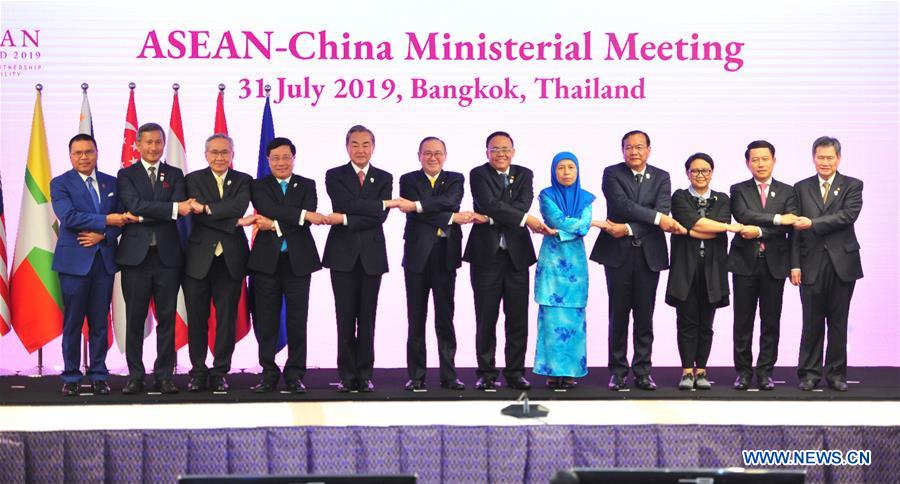

Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (5th L) participated in the China-ASEAN foreign ministers' meeting in Bangkok, capital of Thailand, July 31, 2019. /Xinhua

Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (5th L) participated in the China-ASEAN foreign ministers' meeting in Bangkok, capital of Thailand, July 31, 2019. /Xinhua

In any event, ASEAN warships participating in U.S. "Freedom of Navigation Operations" would add little to deter China from staking its territorial claims and might even be targets for the Chinese military. And should a war emerge, it will be fought on the Southeast Asian countries' territories, destroying properties and causing human lives.

Moreover, Mike Pompeo, in recruiting the Southeast Asian nations to counter "Chinese aggression," was really asking them to buy American arms. His motive, as correctly interpreted by Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, amounts to asking the 10 countries to pay the U.S. for giving up the national interests or in his words, "to commit suicide."

Indeed, buying U.S. weapons would be a gross waste of money because America would not sell the countries advanced weapons but outdated ones. The warships the U.S. sold to the Philippines, Vietnam and other Asian nations, for example, were actually World War Two or Korean War vintage coastal patrol vessels or frigates, hardly enough to "scare" the Chinese away.

Instead of wasting scarce capital on "useless" weapons, the money could be spent on socioeconomic enhancement programs such as skills training. A pool of skilled labor, which most ASEAN members are lacking, is a necessary prerequisite to build an industrial base, attract foreign investment and develop economies.

Furthermore, Asian countries probably realize China did not create the conflicts in the East and South China Seas; the U.S. and Japan did. There were no territorial disputes between China and claimants until U.S. President Barack Obama declared the "pivot" to Asia policy and the Japanese government bought the Diaoyu Islands from their "Japanese owners" in 2012. Ignoring history and fully realizing that China would react strongly against the American and Japanese decisions, the U.S. and Japan, with the help of the media, twisted the narrative, blaming China for the problems.

Up until then, Japan and China were contented with leaving the Diaoyu Islands issues to be addressed by "wiser future leaders." Some Southeast Asian stakeholders were receptive to China's joint development proposal on exploiting the resources in the South China Sea.

Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong correctly observed in an article published in the July/August edition of Foreign Affairs that Asian countries have a lot on their plate, from controlling the spread of the pandemic to overcome the obstacles of economic growth. Resources and energy are needed to address these issues rather than forming a military alliance with the U.S.

And given the strong anti-China sentiment in some Asian countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam as well as being politically unable to compromise on territorial claims, siding with China may not be on the cards. But standing beside the U.S. would risk losing the lucrative Chinese market. Not taking sides is therefore the best policy for ASEAN.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)