Editor's note: Guy Burton is an adjunct professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Iran's nuclear deal – also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – has been portrayed as a diplomatic disaster for the U.S. and a victory for Iran. While the failure of American diplomacy has been visible and humiliating, it is harder to see Iran coming out of this especially well, despite recent announcements crowing at U.S. misfortune.

Its economy is in a poor state and is likely to remain in that state unless a different approach is taken. But for that to happen requires a broader engagement of Iran and its ambitions and rivals in the Middle East rather than focusing on whether or not the JCPOA continues to operate.

The roots of the current crisis began when the U.S. withdrew from JCPOA in 2018 and re-imposed sanctions on Iran unilaterally. Through a strategy of "maximum pressure" it sought to squeeze Iran economically and curtail its regional ambitions and support for other states and groups, like Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen.

The impact of sanctions was soon felt. Iranian oil production fell from 2.5 million barrels per day in 2018 to 223,000 barrels during the first seven months of this year. Fewer production has translated into less oil exports and less government revenue. With the economy having contracted 5.4 percent in 2018 and 7.6 percent in 2019, the IMF predicts that it will drop further this year, by six percent.

Despite the squeeze, U.S. has not been successful in bringing Iran's leaders to the table to negotiate a new deal or to persuade the international community to abandon the JCPOA. As a result, the U.S. tried to do the latter through the UN over the summer. It was only able to win over one country to support its draft resolution, while two permanent Security Council members, Russia and China, vetoed it.

They and the Europeans have stated their commitment to the JCPOA. Having failed to win the argument, the U.S. tried to use the automatic mechanism in the JCPOA to "snapback" UN sanctions. The move was ironic, given that President Donald Trump criticism of the JCPOA as a "bad deal," but was rejected by the UN, which pointed out that the U.S. had withdrawn from the agreement.

American urgency owes much to the electoral timetable. Support for the JCPOA divides along party lines, with the Democrats largely in favor and the Republicans opposed. When campaigning in 2016, Trump said he would replace the JCPOA with a better deal.

But since Trump and the Republicans have been unable to deliver this, they seem determined to trash the current deal before elections in November. Should Democrat candidate Joe Biden win the election, the absence of an agreement would make it impossible for the U.S. to rejoin.

In sum then, the image is of two teams working at odds with each other. While the Americans are trying to pull up the road, the Iranians are feverishly repaving it. But while this provides a neat analogy, it is a far too simple one and overlooks bigger questions regarding Iran and its place in the Middle East.

Even if UN sanctions are not re-imposed via the JCPOA's snapback mechanism, the unilaterally imposed American ones are still in place. They damage Iran and its future prospects, since companies and banks in other countries fear trade or investment, lest they fall foul of the U.S. authorities. One important example of this was the European decision to set up an Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) to provide a means of exchange to avoid U.S. sanctions.

However, it has not proved the boon that many hoped for: only in March 2020 did the first transaction take place for 540,000 U.S. dollars of medical equipment. Similarly, trade and investment with other countries and firms from India, Japan and Korea with Iran has also been severely cut back over the past two years.

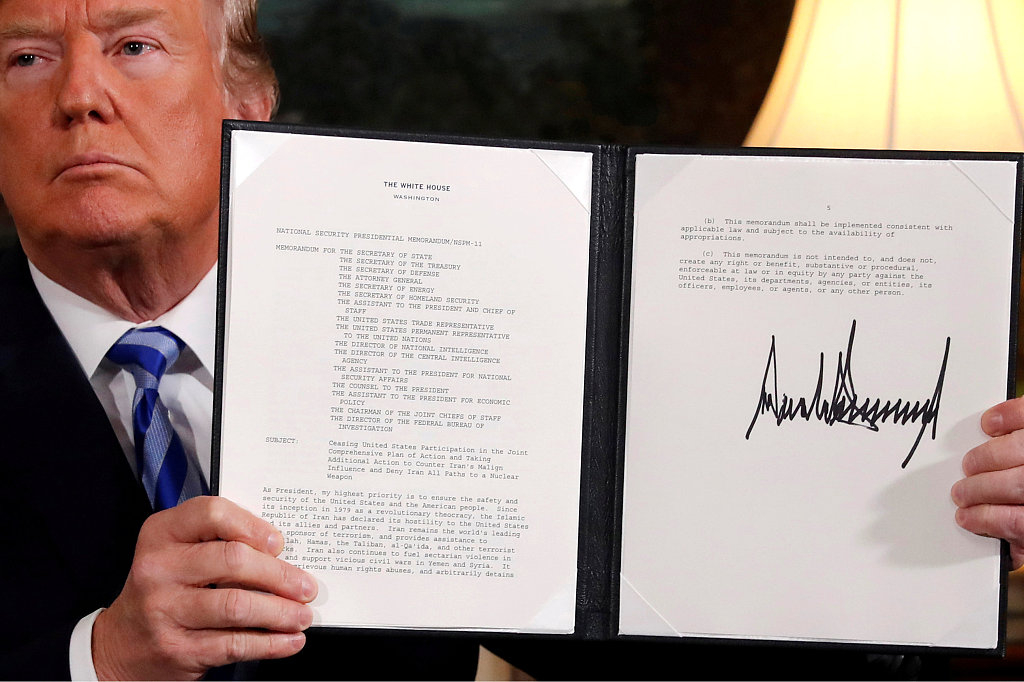

U.S. President Donald Trump holds up a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from theIran nuclear agreement JCPOA after signing it in the Diplomatic Room at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 8, 2018. /VCG

U.S. President Donald Trump holds up a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from theIran nuclear agreement JCPOA after signing it in the Diplomatic Room at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 8, 2018. /VCG

In addition are political questions and challenges for Iran. For one, European support for the JCPOA does not translate into direct sympathy for Iran's leaders and their goals. Rather European involvement is legalistic and conditional, largely on Iran continuing to adhere to the JCPOA's conditions. For another, Iran's public approval of multilateralism over American unilateralism risks it hoisting a petard for itself.

While Iran has long sought autonomy for itself, influenced in large part by the foreign interference it faced by European and American powers over the past two centuries and which seemed to come to an end with the 1979 revolution, that has generated ripples and led to confrontation with regional rivals, including Israel and some of the Arab Gulf states like Saudi Arabia.

The resulting instability has been exacerbated in recent years by growing social and political unrest in the Middle East and the emergence of failed and failing states, from Libya and Syria to Yemen, Lebanon and Iraq. That has also provided space for other parties inside and outside the region – including Iran itself – to insert itself into these conflicts.

What is the solution then? Here Trump had a point: his criticism of the JCPOA was that it was too limited to Iran's nuclear program and failed to deal with Iran's wider regional role and ambitions. But his response was a coercive one: it only partially constrained Iran and did little to build bridges.

Looking ahead, there is a need for both a broader and deeper engagement with Iran and its regional neighbors. Such discussions would be unlikely to lead to a single, standalone agreement such as the JCPOA, but would instead involve several dialogues across different topics and themes and involving a wide range of parties depending on the subject.

Given the recent experience between the U.S. and Iran during the Trump years, the likelihood of that happening should Trump be re-elected is extremely low. Under a Biden administration it may be feasible, but it would require active and sustained commitment over several years. That said, this is not something that should or needs to be left to the Americans alone, but to the wider international community as a whole.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)