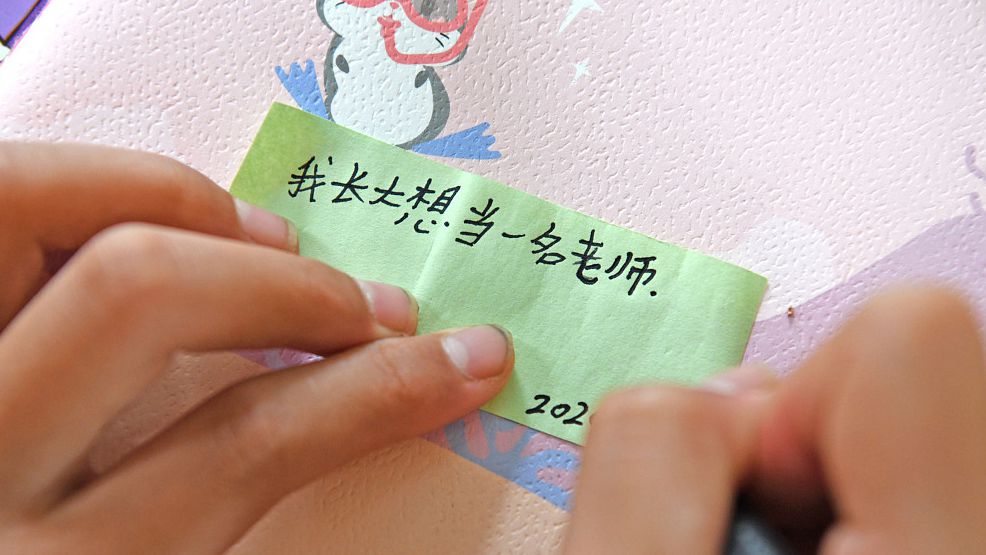

A left-behind child writes that "I want to be a teacher when I grow up" at Kehu Elementary School in Sunmiao Village, Huainan City, east China's Anhui Province, July 31, 2020. /CFP

A left-behind child writes that "I want to be a teacher when I grow up" at Kehu Elementary School in Sunmiao Village, Huainan City, east China's Anhui Province, July 31, 2020. /CFP

Out of more than 10 million students who participated in China's annual national college entrance examinations, or Gaokao, this July, one saw her story capture national attention.

Zhong Fangrong, a "left-behind" girl who grew up with her grandparents in a small village in central China's Hunan Province, scored 676 out of the total 750 points in the exam, coming in fourth among 194,000 liberal arts students in Hunan Province.

Besides her high score, it was the major she chose to pursue at Peking University that caused heated discussions among Chinese internet users: archaeology.

Many internet users worried this would not bring her good job opportunities or a desirable income, unlike other majors such as finance which may have better prospects.

Behind this concern is the idea, common in China, that left-behind children– the daughters and sons of migrant workers who have gone to work in the cities to support their families – often live in poor rural areas and barely have access to good basic education, let alone quality education. The expectation is that students like Zhong, given the chance to study at China's top university and to change their destiny, should pick a major that can help them earn money and improve their quality of life.

A left-behind child use his fingers to learn math at a classroom in Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality, March 23, 2017./CFP

A left-behind child use his fingers to learn math at a classroom in Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality, March 23, 2017./CFP

Independence and potential

To some extent, these images reflect the reality of left-behind children in China. But government policies on poverty alleviation and urbanization have brought about change in recent years.

President Xi Jinping stressed the importance of education in lifting people out of poverty, noting during a tour of Zhangjiakou City in north China's Hebei Province in 2017: "Making sure children of impoverished families enjoy access to high-quality education is a fundamental solution to poverty."

Chinese government rolled out a tuition-free nine-year compulsory education plan – covering elementary and junior high school – and a Free Normal Education Program at six top teaching colleges, to bring graduates to areas with a shortage of teachers.

These policies helped lower drop-out rates among children in rural areas, including left-behind students, and improved the quality of teaching, in turn contributing to higher exam scores in recent years.

One of the top performers in last year's Gaokao, Jiang Mingyu, who scored 667 on the exam, was raised mostly by his grandfather in southwest China's Chongqing Municipality.

A research project carried out from October 2017 to June 2018 led by Lin Danhua, a professor in the Faculty of Psychology at Beijing Normal University, demonstrated why left-behind children have great potential: nearly 60 percent of these children learn how to take care of the household on their own at a young age and are able to care for themselves.

Left-behind children enjoy their lunch at Feiye Elementary School in Peihai Town, Shangrao City, east China's Jiangxi Province, September 3, 2020. /CFP

Left-behind children enjoy their lunch at Feiye Elementary School in Peihai Town, Shangrao City, east China's Jiangxi Province, September 3, 2020. /CFP

These skills help them study and think independently, which plays an important role in their learning achievements, said Yu Wenzhi, a teacher at Xin'an High School in Huaining County, east China's Anhui Province.

Zhong's choice of archaeology points to this kind of independent thinking: rather than monetary concerns, she picked a subject she loved and was really interested in.

"I like history and culture relics since my childhood. And under the influence of Fan Jingshi, a highly regarded Chinese archaeologist, I choose to study archaeology in Peking University," Zhong said on her account of China's Twitter-like Sina Weibo.

She also had the support of her parents, who migrated to south China's Guangdong Province to work when the girl was a toddler.

As people's livelihoods have improved with the country's technological and economic development, more and more Chinese have begun pursuing their real interests.

Two university students wearing red hats play games with Wang Yanrong in Guanduo Village, Baidian Town, Haian City, east China's Jiangsu Province, August 5, 2020. /CFP

Two university students wearing red hats play games with Wang Yanrong in Guanduo Village, Baidian Town, Haian City, east China's Jiangsu Province, August 5, 2020. /CFP

According to a 2019 survey by Beijing Normal University, several college majors that used to be unpopular – such as history, museology, Chinese language and literature, and psychology – have become the most popular majors among high school graduates born in the 2000s.

Challenges ahead

However, there is still a long way to go until each left-behind child can have the best opportunities.

There are over 290 million rural migrant workers nationwide, making up the majority of the nation's labor force, according to data released by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

More and more now choose to bring their children with them when they move to the cities, instead of leaving them with relatives.

A report by an NGO named Facilitator last month showed that about 85 percent of migrant workers from 12 provinces – including east China's Anhui Province and central China's Henan Province, where most migrant workers come from – chose to have their family members, including their children, with them.

But other parents choose differently and so there are many children growing up mostly on their own and with the help of their family members.

A migrant worker goes shopping with her children on a street in Dongguan City, south China's Guangdong Province, February 14, 2015. /CFP

A migrant worker goes shopping with her children on a street in Dongguan City, south China's Guangdong Province, February 14, 2015. /CFP

Moreover, under China's hukou system of residence, most migrant students have to go back to their hometown to take their college entrance examination. Many return before the exam to prepare for it since provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions don't share the same textbooks or examination papers.

"Most of my classmates said they went back to study in their hometowns," Li Xiaonan, a 10-year-old whose school was demolished, said during her speech at the launch in Beijing on August 30 of Facilitator's report on the vulnerability and potential risks for migrant workers' families during COVID-19.

The progress of China's urbanization, which has seen the country's rural population increasingly move to the cities, means children who were previously left behind have more and more chances to realize their dreams.

But there are still challenges ahead. "The integration of urban and rural areas needs time," said Yang Tuan, a researcher on social policy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in an interview with CGTN Digital.