13:21

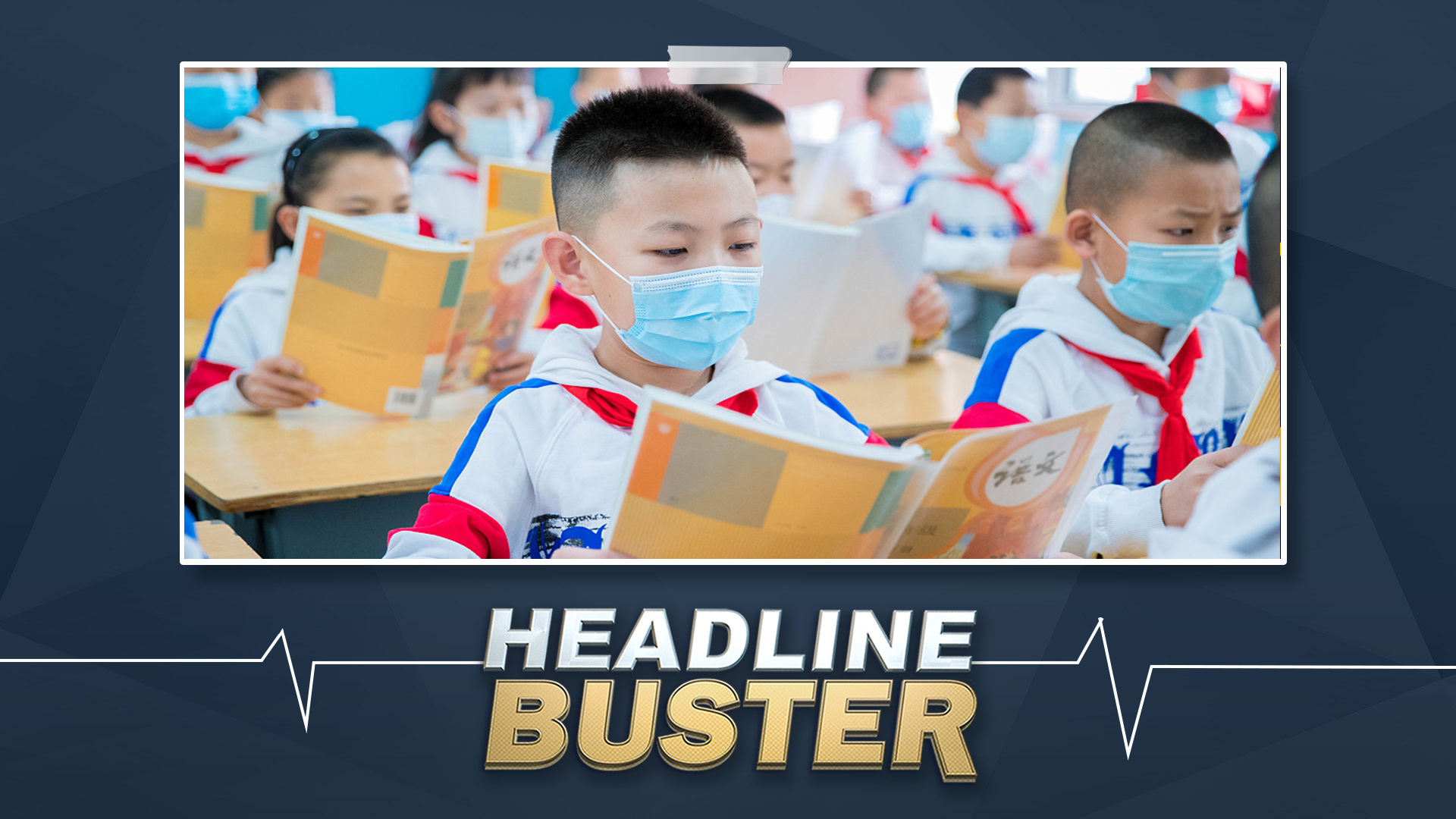

China launched a new curriculum for some students in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, which went into effect on the first day of schools this year. First-graders at schools for minority groups will now use unified national textbooks for their Chinese language and literature course, which are taught in Mandarin, the official national spoken and written language of China, instead of Mongolian, the language traditionally used by the Mongolians living in the area.

The change has triggered fears that Mandarin will be replacing Mongolian in schools, or that the policy is part of a wider campaign to eliminate Mongolian culture. But that's just not the case.

Here's what's changing:

In addition to this year's shift, courses on Ethics and Law will be taught to first graders in Mandarin, starting in fall of 2021. In 2022, first graders will also start taking History courses in Mandarin.

Here's what's not changing:

Courses like math, science, and art will still be taught in Mongolian, and the region's bilingual education in these schools will not be scrapped. Except for these three new courses for first graders, the curriculum for other subjects and grades, as well as the textbooks and teaching language, will remain unchanged. The lesson hours of Mongolian and Korean, another language used by ethnic minorities in the region, will also remain unchanged. Opportunities for bilingual education will still exist in the region, and everyone is free to speak or used their mother tongue.

Still, being fluent in Mandarin is important in China. China's Constitution and the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language promote the normalization and standardization of Mandarin, as well as the economic and cultural exchange among all the Chinese ethnic groups and regions.

However, that same law also says ethnic groups have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages. Protecting ethnic minority groups' language and culture has always been important in China. Learning Mandarin from an earlier age will not take that away.

The overall idea is to make students more competitive and ensure courses linked to national identity are taught consistently, but without depriving people of their identity. When you read some of the media reports, however, a more alarming picture emerges.

CNN on September 5 published the story, "How China's new language policy sparked rare backlash in Inner Mongolia," saying, "Under the new policy, Mandarin Chinese will replace Mongolian as the medium of instruction for three subjects in elementary and middle schools for minority groups across" the region. But it doesn't specify that the changes only apply to first graders or that the rest of the classes will still be taught in Mongolian. One of the article's sections is even titled "Mandarin Replaces Mongolian", which is eye-catching, but not accurate.

Criticism is rife throughout the article, which highlights fears that the move spells an “end for the already waning Mongolian culture.” But only a few lines are dedicated to how the change could impact minority students' paths to higher education and employment.

A Wall Street Journal article from September 3 reads, "China Clamps Down on Inner Mongolians Protesting New Mandarin-Language Rules: Region's ethnic Mongolians fear Beijing's education policies are phasing out local history and literature, erasing their culture.”

The article opens not with what the policy is or why it's being rolled out, but rather: "Chinese authorities are searching for protesters in Inner Mongolia after a new policy aimed at pushing Mandarin-language education across the region sparked widespread unrest among the country's ethnic Mongolians, with many angered by what they saw as a move to erase their culture."

Concerns are understandable. Change can be hard, and maybe details about the policy could have been better explained. But for the article to center the whole story around backlash comes across as politically motivated. More attention could have been given to families that have welcomed Chinese language instruction and believe it could better prepare their children to compete for spots at universities and companies amid an increasingly competitive environment.

There are multiple perspectives that deserve attention, and we should keep digging deeper to present voices from all sides to understand the full story.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)