Editor's note: Joel Wendland-Liu is an associate professor of the Integrative, Religious and Intercultural Studies Department of Grand Valley State University in the U.S. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

It has the earmarks of a typical U.S. intelligence operation. Government documents are "leaked" to the media. The media publishes the government's views without much reporting other than quoting intelligence-created and approved sources.

The State Department and covert agencies provide millions of dollars in "aid" to "dissidents" who spread false and misleading information about the target government. Funds are secretly and sometimes illegally plowed into "political opposition" groups who often promote violence and instability in the target country.

U.S. politicians, who suddenly act concerned about democracy and human rights, give impassioned speeches that lend a veneer of morality to the concerted effort against the target country.

Human rights organizations, which rely on wealthy donors, often with connections to the U.S. intelligence community, politicians, and interested corporations, join the narrative. They do not want to appear "disloyal," which means appear to be critical of U.S. foreign policy or not anti-communist or anti-terrorist enough. Either way, both reporters and human rights investigators reproduce intelligence narratives because they want to be the next Bob Woodward or Jane Goodall.

In the end, they are often willing mugs of an expensive but effective intelligence scheme. This scenario is the rubric for manufactured U.S. accusations about China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

The operations' patterns are time-worn. U.S. media outlets know they are used for these purposes. For example, in late 2002 at the peak of the Bush administration's campaign to start the Iraq war, The New York Times celebrity journalist Judith Miller reported that top government sources had evidence that Iraq was manufacturing aluminum tubes needed to make nuclear weapons. This story helped solidify support for the war.

It turns out the story was false. Indeed, the "sources" for it came directly out of the Bush administration. After the fabricated information was leaked, Vice President Dick Cheney used The New York Times story to justify the administration's demand for war. The Bush administration also branded war opponents as allies of terrorism, extorting loyalty from waffling politicians, government professionals, and ambitious media personalities.

In 2004, when no nuclear weapons facilities were discovered after the deaths of tens of thousands of Iraqis, the truth of how this intelligence operation depended on manipulating a media personality came out.

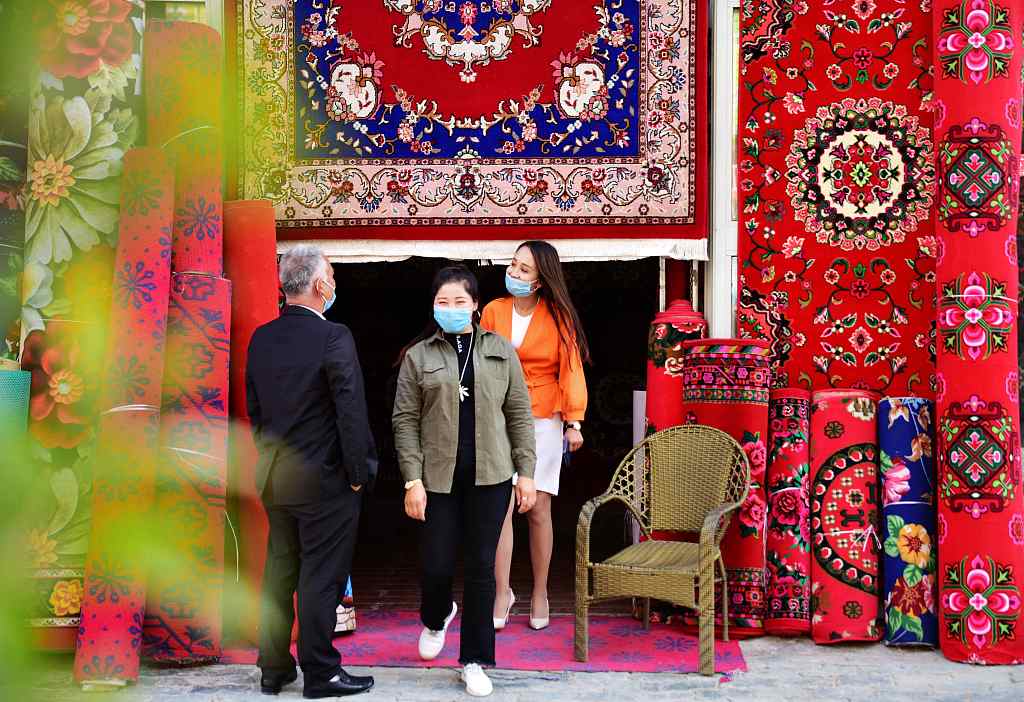

Streetview in Aksu, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. /VCG

Streetview in Aksu, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. /VCG

The intelligence community's role in major media outlets has been outstripped in recent years by its influence over right-wing publications and websites, according to analysis by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. Right-wing media outlets and websites are regularly used to disseminate the foreign policy narrative and to pressure dissenters.

A vital distinction between the Bush administration's Iraq war operations and the Xinjiang operation is that parts of the U.S. intelligence community saw little strategic advantage in the Iraq war. Divided, some opponents of the war deployed their own public relations operations and leaked information that discredited the Miller story.

Today, the U.S. intelligence community is united in its fear of China's new role in global politics as an economic leader. China's lead in technology and exports, upon which much of U.S. capitalism depends, has U.S. elites in a panic.

China's global influence and leadership outshine the U.S.'s deservedly tarnished image. An internal crisis of the U.S. state and its illegitimacy (see the failed COVID-19 response combined with systemic racism) is pushing the U.S. political class from its self-constructed stage of unipolar dominance.

Within this crisis context, the U.S. intelligence community has returned to its traditional intervention and global manipulation methods. In his new book, "The Jakarta Method", a carefully reported and historically vetted study of the 1965 U.S. role in the mass killing of 1 million Indonesians, journalist Vincent Bevins shows how this type of operation has been a staple of the U.S. intelligence community.

Bevins recounts the CIA role in U.S.-orchestrated coups and interventions, which almost always depended on covert operations like those described above and mass killing campaigns for which Indonesia served as a model. Focusing on the Cold War, Bevins writes, "I do want to claim that this loose network of extermination programs, organized and justified by anti-communist principles, was such an important part of the U.S. victory that the violence profoundly shaped the world we live in."

Bevins shows how illegal interventions and mass killings are fundamental to U.S. power, giving the lie to its claims to be a democratic and human rights leader for the world.

The U.S. people deserve better than a society based on so much human suffering. They deserve to know they can trust their government. The truth, however, is that faith in the current system is misplaced. Unfortunately, without a fundamental systemic change in how the U.S. government works in relation to the rest of the world, the truth about what it is up to seems only to come out after so many millions die.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)