Were it not for the moon, Chinese romanticism would have been a great deal drier.

For hundreds of years, the globe that lightens the darkness of the sky has been one of the most loved poetic vessels filled with emotions from infatuation, to solitude and nostalgia.

The full moon derives its literature aesthetics from its looks. In its round shape, Chinese culture reads a sense of perfection. The character for the shape is often associated with happy affairs such as family reunion and the fulfillment of love. Consequently, the feelings of void and sorrow well up within romantic souls with the caprice of lunar appearances.

As a hybrid of performance and literature art, Peking Opera has inherited rich moon symbolisms from romantic literature. By colloquializing poetic language in its hundred-year-old classics, which are readapted from folklores and old novels, the art form has created catchy lines in vernacular that the illiterate were able to appreciate. After more than two centuries of refinement, these lyrics have become classics in their own right.

Days before China's Mid-Autumn Festival (on October 1 this year, coinciding with the Chinese National Day) when people admire the full moon, we would like to spread the appreciation for the festivity by inviting our readers to a challenge of translating a few famous lines from Peking Opera classics into English. They are mostly soliloquies with which the characters express deep feelings by means of moon references. CGTN is fully aware of the cultural gap that may underline the linguistic challenge. To help readers with the translation, details are provided below on the operas' storylines – the figures uttering the lyrics in question.

The best translations, as established by our panel of Peking Opera experts and readers, will win the authors a small gift kindly provided by China National Peking Opera Company.

A piece of mooncake and a cup of Chinese tea may also be helpful with getting into the mind-set of the characters.

Good luck and happy Mid-Autumn Festival!

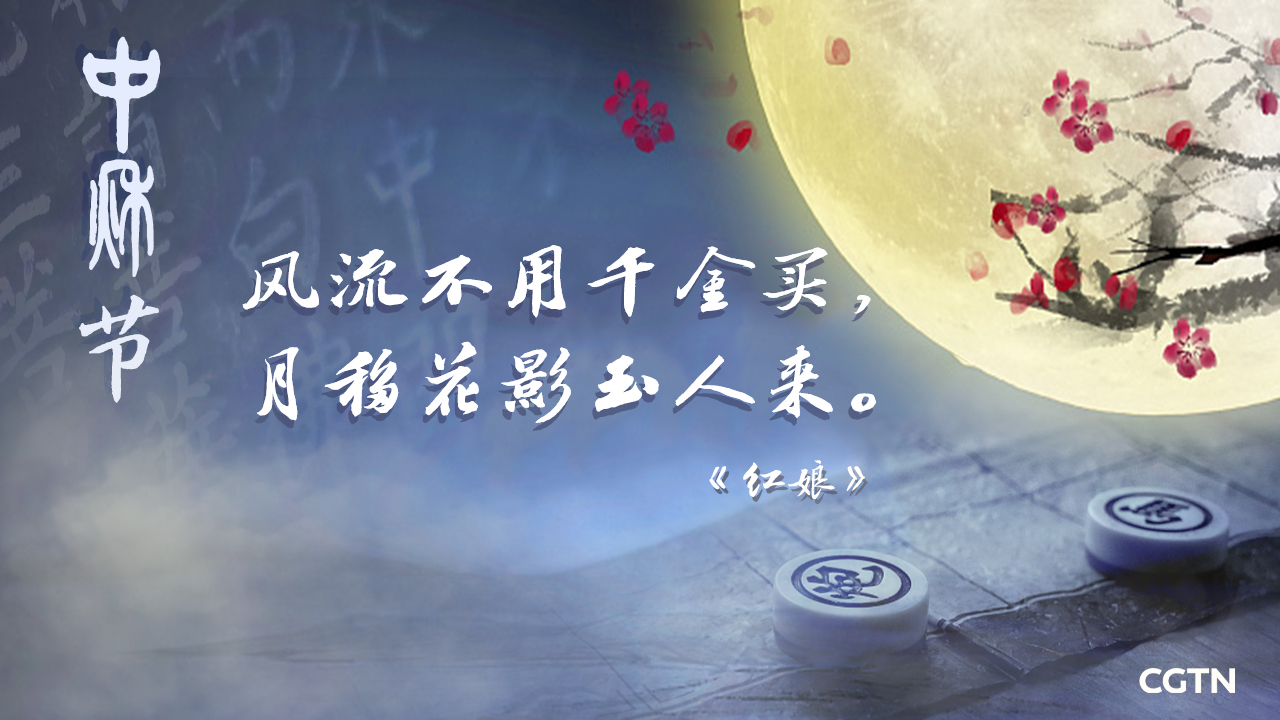

红娘/Hongniang

Marrying for love was a luxury during China's imperial era when parents were entitled to forcing marriage upon their offspring. The titling figure of this opera, Hongniang, is a clever and brave maid who helps her lady tie the knot with her true love despite a disapproving mother. The story is so popular that the name "Hongniang" has come to mean "matchmaker" in the Chinese vocabulary.

What Hongniang, the "matchmaking maid," looks like in Peking Opera.

What Hongniang, the "matchmaking maid," looks like in Peking Opera.

Hongniang utters the lines "风流不用千金买,月移花影玉人来," after she has successfully arranged a secret date for her mistress to meet her lover at night, feeling both happy for the pair and a sense of triumph over a social taboo that stands in the way of true love.

武家坡 Wujia Po

Wang Baochuan, a wife waits in grinding poverty for 18 years for her husband Xue Pinggui, a general of the Tang court, to return from the battlefield. Yet both have aged so much that they hesitate to recognize each other when he shows up at her door at Wujia Po where she lives in a shanty. Sensing his wife's reluctance, the suspicious Xue decides to test her faithfulness by flirting with her, pretending to be her husband's acquaintance.

A scene from the opera Wujia Po. Wang Baochuan (L) is angered by her long-missing husband (R) who in the scene is posing as a flirtatious stranger to test her loyalty upon their reunion after 18 years.

A scene from the opera Wujia Po. Wang Baochuan (L) is angered by her long-missing husband (R) who in the scene is posing as a flirtatious stranger to test her loyalty upon their reunion after 18 years.

The line quoted here, "八月十五月光明," chanted by Xue, kick-started one of the most dramatic reunions of two spouses in Peking Opera classics.

野猪林 Yezhulin/ Boar Forest

"Shui Hu Zhuan," or Water Margin, is one of the best-known novels in China that descends from the 14 century. Setting in the Song Dynasty, it romanticizes a famous organized rebellion against the court, leaving the images of 108 heroes sealed in the minds of generations of Chinese people.

The looks of Lin Chong, the tragic character from Shui Hu Zhuan, or Water Margin, in Peking Opera.

The looks of Lin Chong, the tragic character from Shui Hu Zhuan, or Water Margin, in Peking Opera.

Lin Chong is arguably the most tragic hero in the book. As a court guard martial art instructor, he is jolted out of his shielded life after being set up by a jealous colleague and wronged by a corrupted supervisor. In exile far from his family and almost killed by enemies in Yezhulin (or Boar Forest), the desolate hero sings the following words: "问苍天,缺月何时再团圆."

西厢记 Romance of the West Chamber

The opera storyline centers in Hongniang (see above) and is a re-adaptation from the dramatic work of the same name by Wang Shipu of Yuan Dynasty, featuring the matchmaking maid's mistress, Cui Yingying, and her lover Zhang Junrui as the leading characters.

The Peking Opera version of Romance of the West Chamber. The character in white is Cui Yingying, the woman protagonist.

The Peking Opera version of Romance of the West Chamber. The character in white is Cui Yingying, the woman protagonist.

The line "空对着月儿圆清光一片,好叫人闲愁万种,离恨千端" is part of the woman protagonist's soliloquy after she learns her mother's strong disapproval of her lover and the match, and sinks into depression.

Love can be elusive, even to the absolute power of an emperor.

Li Longji, the "Illustrious August" of Tang, is probably the most romanticized of all the rulers of the Middle Kingdom in China's literature, largely because of his ill-fated love tale with his consort Yang Yuhuan.

The emperor's rein stretched over the pinnacle of Tang Dynasty, ending in humiliation brought on by a devastating rebellion due mainly to his ill-placed trust. Fleeing Chang'an, Tang's capital, with the concubine, Li found he was pressed to order his lover's execution by angry courtiers, who were convinced that she was to blame for corrupting the ruler's mind and the empire's ordeal.

The character of Yang Yuhuan in Drunken Concubine.

The character of Yang Yuhuan in Drunken Concubine.

The Drunken Concubine is set in the time when the usurpers still took care to humble themselves. Promised the emperor's company, Yang throws a feast and waits in desperation only to be told he has stayed with another consort. Drowning her sadness and jealousy, Yang soon loses her bearings, singing the soliloquy that includes the line “皓月当空,恰便似嫦娥离月宫,” in which she compares herself to Chang'e, the Chinese deity that lives in forever loneliness on the moon.

霸王别姬 Farewell My Concubine

In the story, the Hegemon-King Xiang Yu retreated to the bank of Wujiang river. His rivalry with Liu Bang, the later founding emperor of the Han Dynasty, for the dominance of the Middle Kingdom, was drawing to the wrong end. Two options lied ahead of the defeated man: To run in humiliation or die head held high. He chose the latter.

In terms of the tragic effect of every later dramatization of the war, the scene where Xiang Yu puts himself to the sword is probably only second to the one in which he asks his concubine, Consort Yu, to leave him for life. She refuses, devoting her life to proving her love to him – a heart-breaking twist the opera Farewell My Concubine culminates in. In the soliloquy before she resigns to end her life, the concubine chants: "猛抬头见碧落月色新明."

Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang (L) plays Concubine Yu in "Farewell My Concubine", together with Yang Xiaolou (R) who plays Xiang Yu, 1920s.

Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang (L) plays Concubine Yu in "Farewell My Concubine", together with Yang Xiaolou (R) who plays Xiang Yu, 1920s.

The opera is closely associated with the name of Mei Lanfang, China's most famous Peking Opera master, whose portrayal of Consort Yu since the beginning of the 20th century remains an insurmountable performance today.

(Pictures designed by Feng Yuan and Li Jingjie)