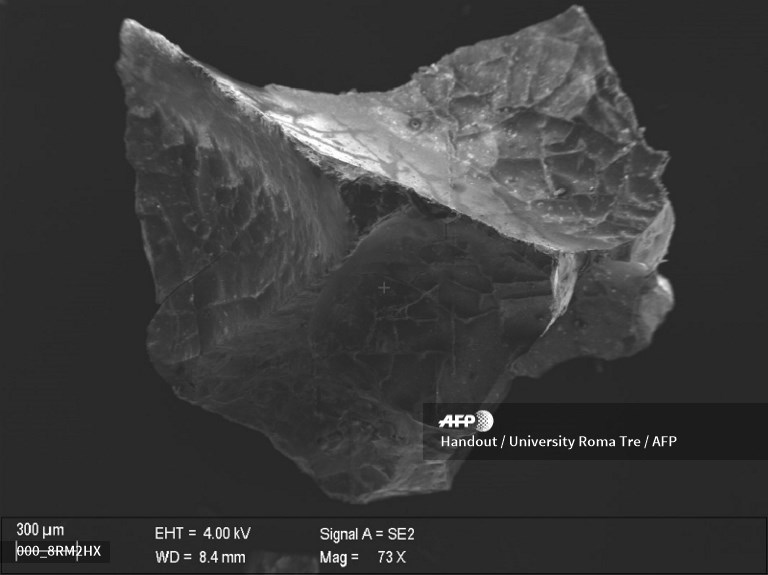

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. /AFP

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. /AFP

Brain cells have been found in exceptionally preserved form in the remains of a young man killed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius almost 2,000 years ago, an Italian study has revealed.

The preserved neuronal structures in vitrified or frozen form were discovered at the archaeological site of Herculaneum, an ancient Roman city engulfed under a hail of volcanic ash after nearby Mount Vesuvius erupted in the year 79.

"The study of vitrified tissue as the one we found at Herculaneum ... may save lives in future," study lead author Pier Paolo Petrone, forensic anthropologist at Naples' University Federico II, told AFP.

"The experimentation continues on several research fields, and the data and information we are obtaining will allow us to clarify other and newer aspects of what happened 2000 years ago during the most famous eruption of Vesuvius," said Petrone.

A SEM image of brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. /AFP

A SEM image of brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. /AFP

The victim whose samples were examined was a man aged around 20 whose remains were discovered in the 1960s splayed on a wooden bed.

The extreme heat of the eruption and the rapid cooling that followed essentially turned the brain material to a glassy material, freezing the neuronal structures and leaving them intact, Petrone explained in the study, published on Tuesday by U.S. peer-reviewed science journal PLOS ONE.

"The evidence of a rapid drop of temperature – witnessed by the vitrified brain tissue – is a unique feature of the volcanic processes occurring during the eruption, as it could provide relevant information for possible interventions by civil protection authorities during the initial stages of a future eruption," according to Petrone.

A room at the archaeological antiquity site of Herculaneum, where scientists found brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. /AFP

A room at the archaeological antiquity site of Herculaneum, where scientists found brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. /AFP

Vesuvius' eruption covered Herculaneum in a toxic, meters-thick layer of volcanic ash, gases and lava flow which then turned to stone, encasing the city, allowing an extraordinary degree of frozen-in-time preservation both of city structures and of residents unable to flee.

As they investigated the organic material turned up by the study, researchers managed to obtain unprecedented high resolution imagery using scanning electron microscopy and advanced image processing tools.

With the post-eruption preservation locking in the cellular structure of the victim's central nervous system, researchers have seized on the chance "to study possibly the best known example in archaeology of extraordinarily well-preserved human neuronal tissue from the brain and spinal cord," PLOS ONE noted.

Source(s): AFP