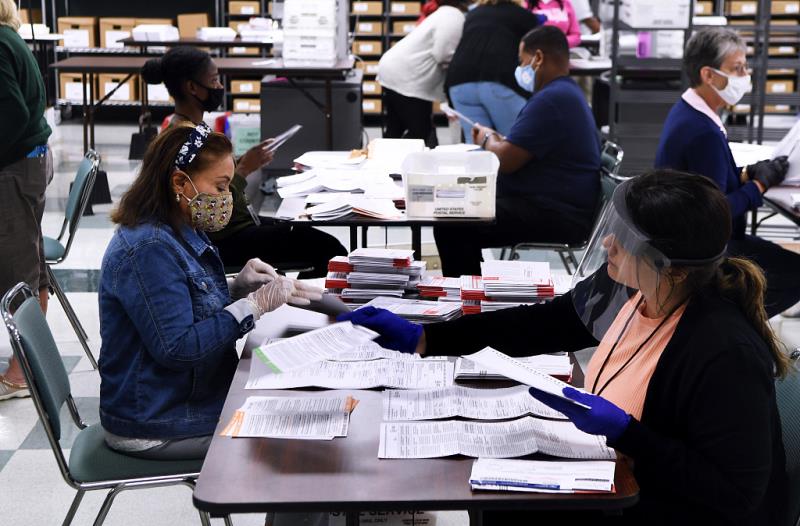

Staff at the Santa Clara County Voter Registration Office handle postal votes in San Jose, California, U.S., October 13, 2020. /VCG

Staff at the Santa Clara County Voter Registration Office handle postal votes in San Jose, California, U.S., October 13, 2020. /VCG

International observers are usually associated with elections in fledgling democracies and developing countries, but dozens of them will be on hand to watch the U.S. presidential race up close on November 3 – and not only because of President Donald Trump's repeated warnings of fraud at the polls.

Over the past few months, Trump has time and again claimed that the Democrats will try to rig the election and that mail-in ballots can be faked. In the first debate against his Democratic rival, former Vice President Joe Biden, Trump urged supporters on election day to "go into the polls and watch very carefully," raising fears of voter intimidation.

Against this backdrop, international observers are heading to the U.S. to report on whether the election is free and fair.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which counts the U.S. among its 57 members, has already sent around 40 international observers and experts to monitor the situation in the run-up to the vote. The mission is being carried out by the OSCE's Warsaw-based Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR).

The OSCE's Parliamentary Assembly (OSCE PA) will also send a separate team made up of some 100 deputies from national parliaments.

Double standards

This won't be the first time that international groups monitor a U.S. election: both ODIHR and the OSCE PA have been observing presidential and midterm elections there since the early 2000s.

Karl Oellinger, a former Austrian MP who was part of the OSCE PA team sent to monitor the 2012 U.S. presidential election, said this arrangement was the result of a years-long debate.

"The OSCE's 'western' member states were accused of double standards by the 'eastern' states, where election monitoring was carried out almost exclusively for a long time," he told CGTN. Only in the last decade or so has it become "self-evident" that western countries should also be open to election monitoring.

A tricky election year

Still, this year has thrown up a fresh set of hurdles.

American voters visit a polling station to vote early for the November 3 general election in Miami, Florida, October 21, 2020. /VCG

American voters visit a polling station to vote early for the November 3 general election in Miami, Florida, October 21, 2020. /VCG

The Organization of American States (OAS), which observed the last presidential election in 2016, failed to receive an invitation from the U.S. government this time around, according to The Guardian. Efforts by CGTN to contact the OAS remain unanswered. All international monitors require an invitation in order to observe an election.

ODIHR, which had initially planned to send about 500 observers, decided instead on a limited mission with a 10th of that number as it struggled to secure participation from OSCE member states. "This year has been a big challenge for all of our election-related work, and particularly for the deployment of observers... it's just been difficult to sign the numbers this year," ODIHR spokesperson Katya Andrusz told CGTN.

Travel restrictions and health concerns due to the COVID-19 pandemic also forced the OSCE PA to shrink the number of people it was sending.

"When we opened up registration process and invited members to sign up, there was a lot of interest, over 100 sign-ups, but that number has decreased and some of that is the result of travel problems," OSCE PA spokesman Nat Parry told CGTN. Among others, the UK delegation, which was set to include 11 MPs, had to withdraw.

What do observers do?

For those actually traveling to the U.S., observation work begins long before election day.

The ODIHR mission – which includes experts and observers from 21 countries, including Germany, Estonia, North Macedonia and the Czech Republic – has been on the ground since late September-early October and will have been monitoring the situation for a month by the time the big day comes around.

"The run-up to the election and its aftermath are extremely important and we really take very seriously the necessity of analyzing the pre-election environment, the legal framework, the work of the administration and its effectiveness, the campaign financing, campaign management but also the campaign atmosphere, for example the use of negative or intolerant rhetoric, any freedom of media issues and the media coverage as a whole," noted Andrusz.

People queue in front of a polling station to vote early in Florida, U.S., October 19, 2020. /VCG

People queue in front of a polling station to vote early in Florida, U.S., October 19, 2020. /VCG

During past U.S. elections, voters have complained of having to queue for hours to cast their ballot and of problems with voting machines, voter registration and untrained staff. During the primaries earlier this year, COVID-19 fears also resulted in the closure or last-minute relocation of many polling stations – in part due to a shortage of poll workers, as many tend to be elderly and more at risk of falling ill – leading to widespread voter confusion.

"One of the things that we look at very carefully... is whether people are free to vote, that they are not hindered from voting. Voters need to be enabled to make use of their right to vote," said Andrusz.

On November 3, ODIHR's observers will be deployed across 15 states.

The OSCE PA will meanwhile send an advance team at the end of this week to have meetings with state and local officials. The rest of the 100-strong observer mission will then head to the U.S. in late October and attend two days of briefings and discussions with experts, media and voting rights organizations in Washington, D.C. before deploying to about 10 states, including swing states like Michigan, North Carolina and Wisconsin, said Parry.

The aim on election day is for each group to visit about 10-20 polling stations and also observe how postal votes are collected and tallied.

"It's part of the observation process... Usually they would go to a polling place as it's closing and ask to observe as ballots are counted and the tabulation process."

On-the-ground hurdles

But whether the observers are granted access is not guaranteed. Besides safety rules related to the pandemic, it "can be hit or miss in terms of how much access you're given and whether the person in charge there will let you in or not," said Parry.

Several states, like Arizona, Florida and Ohio, explicitly ban international observers, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). In 2012, Texas Governor Greg Abbott threatened OSCE observers with criminal charges if they entered a polling station.

Election staff scan and process mail-in ballots at a voter registration office in Orange County, Florida, U.S., October 20, 2020. /VCG

Election staff scan and process mail-in ballots at a voter registration office in Orange County, Florida, U.S., October 20, 2020. /VCG

While election observers coordinate with state authorities to secure permission to visit polling places, the decentralized nature of the U.S. electoral system means local officials may still block observers.

Oellinger recalled that in 2012 the board of elections in North Carolina, where he was based, assured the observers that they would be able to carry out their work unhindered and that local election offices had been informed of their visit. But on the day itself, teams were turned back at some polling stations, despite having badges and documentation granting them access.

Even where they were granted access, they were unable to conduct detailed checks, which generally include about 30 minutes of close observation and interviews with the head of the polling station, poll watchers and others.

"We were just visitors who were allowed to observe the proceedings for a short period of time," Oellinger, who also observed elections in Albania, Kazakhstan and Georgia, deplored. "The authority of the state board of elections over officials in each individual polling station is clearly very limited," he added.

An independent view

Election monitoring teams cannot guarantee a fair election: they are there to observe, as Oellinger pointed out.

In its assessment report for its U.S. mission, ODIHR noted that this election "will be the most challenging in recent decades."

But "in a highly polarized environment, there is an increased need for external and independent overview of the electoral process," it concluded.

Despite likely complications along the way, including local restrictions and last-minute changes due to the pandemic, "we are still confident that as well as being fully objective, we will have an accurate and credible assessment of the election," said Andrusz.