A spray-painted sign encourages people to vote early in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 27, 2020. /VCG

A spray-painted sign encourages people to vote early in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 27, 2020. /VCG

U.S. elections are among the most watched around the world. Yet, every four years, people around the globe gaze at the spectacle of presidential elections and try to make sense of how they work. And given the number of websites, videos and news reports that seek to clarify the process in the run-up to election day, quite a few U.S. citizens are similarly confused.

So here is a look at some of the quirks of U.S. presidential elections.

Why is election day always on a Tuesday?

In many countries, elections can be called at any time during the year. They are also often held on a Saturday or Sunday, when people have the day off and have time to vote. Not so in the U.S.

An 1844 statute set the presidential election "on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in the month of November" — meaning any Tuesday between November 2 and 8.

At the time, this made sense as it enabled farmers, who made up a large part of the population and often lived far from their polling station, to vote on their way to town for market day on Wednesday.

But in recent years, with Tuesday now a working day, there have been concerns that some people are unable to make it to their polling station. Civil rights advocates have called for election day to be made a federal holiday so that people have the day off to vote.

Voting... how?!

A characteristic of the U.S. system is that it is very decentralized: that means that although the whole country may be voting for the same president, each state makes up its own rules on how people can vote. And this has led to quite a lot of confusion.

Only one state does not require people to register in order to vote: North Dakota. In all others, the deadline for registration and how to go about it differs. In some places like New Hampshire, Idaho and Hawaii, voters can still register at their polling station on election day, while others require registration 30 days before. Forty states and the District of Columbia allow online registration, but others require it to be done by post or in person.

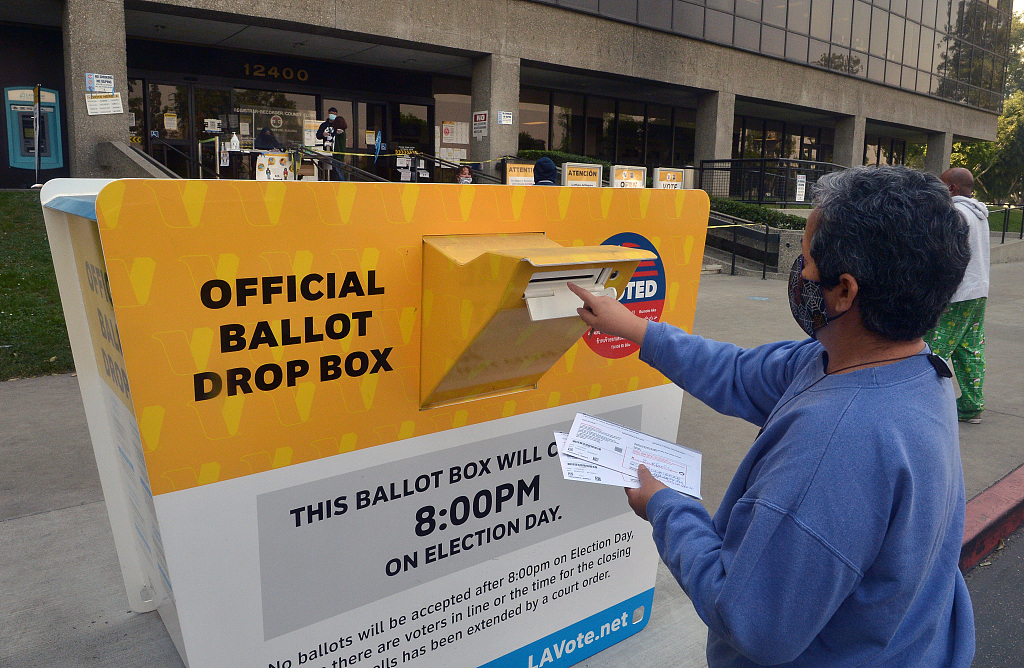

A voter drops off ballots in an official ballot drop box in Los Angeles, California, October 27, 2020. /VCG

A voter drops off ballots in an official ballot drop box in Los Angeles, California, October 27, 2020. /VCG

This year, early voting has been expanded, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic as authorities have tried to limit the number of people crowding into polling stations on November 3. But opening times again vary greatly from state to state. South Dakota and Minnesota (September 18 to November 2), as well as Vermont (September 21 to November 2) have had among the longest early voting periods. Voters in Oklahoma meanwhile can only vote early between October 29 and 31.

To make things a little more complicated, different states also use different voting equipment. While some polling stations have switched to electronic voting, others have remained loyal to paper ballots. Some voting machines also provide a paper record, in case of a recount or audit, but others don't.

As for those who enjoy casting their ballot in person, tough luck if you live in Oregon or Hawaii, as the two states have transitioned entirely to mail-in voting.

Mailing in your ballot

Several states have expanded mail-in voting this year as a way to let people vote safely during the pandemic. But this, too, has come with some tricky caveats.

Washington, California, Oregon, Colorado and Hawaii have automatically sent mail-in ballots to all registered voters. Elsewhere, voters need to request one. But some states, like Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi, require a specific reason for requesting a mail-in or absentee ballot – such as being 65 years old or older, being ill or physically disabled, being in prison or on jury duty.

Mail-in ballots can be returned in person or via post, email, fax or an official election drop box, depending on the state. But in Missouri, voters are additionally required to get a notary's signature on their mail-in ballot. In North Carolina and South Carolina, they need one witness' signature, while Alabama requires either a notary or two witnesses.

How long is the ballot?!

The battle for the White House tends to overshadow everything else, but on November 3, U.S. voters will not just be picking their next president, but also senators, sheriffs and district attorneys, as well as deciding on local policy initiatives. This means a ballot can extend to several pages. And it will differ not just from state to state, but also from county to county.

A voter uses an electronic voting machine at a polling station in Washington, DC, October 27, 2020. /VCG

A voter uses an electronic voting machine at a polling station in Washington, DC, October 27, 2020. /VCG

A sample ballot posted by the Office of the Mississippi Secretary of State features nine possible pairings for president and vice-president, as well as choices for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, and the Mississippi Supreme Court.

In another sample ballot for Michigan, voters are asked to vote on circuit court judges, local school district board members, leadership positions in several universities and even the positions of county clerk and treasurer.

Meanwhile, some 120 policy initiatives are on the ballot across the country, touching on everything from abortion to taxation and sports betting.

While other countries may hold separate presidential, general and local elections, in the U.S. they are, to a certain extent, all wrapped up in one.

Can or can't vote?

One of the most controversial issues in U.S. elections has been that the idea of "one man, one vote" does not always apply. In some states, anyone convicted of a felony can be stripped of their right to vote, sometimes for life. Only Maine, Vermont and the District of Columbia allow people to vote while in prison.

According to The Sentencing Project, about 5.2 million people will be barred from voting this year due to felony disenfranchisement. In state likes Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi, this represents over 8 percent of the population, many of them African-Americans and Latinos.

Some changes over the past few years have contributed to an overall drop in disenfranchised voters. However, a 2018 Florida amendment allowing convicted felons to vote again once they have completed their sentence hit a new snag last year. The matter is being decided in the courts.