Editor's note: CGTN's First Voice provides instant commentary on breaking stories. The daily column clarifies emerging issues and better defines the news agenda, offering a Chinese perspective on the latest global events.

October 28 marked the second round of Pompeo's anti-China trip around Asia. Determined to cement his foreign policy legacy in stone before the election shifts political priorities, the Secretary of State visited the island nation of Sri Lanka after stopping in New Delhi to pursue several defense agreements the day before. Not surprisingly, while in Colombo, Pompeo resorted to a tirade against the island's ties with Beijing and pitched himself as truly knowing what constitutes their best interests, branding the Communist Party of China a "predator" and stating that the country had made "bad deals." He then unconvincingly pitched the United States as a "true partner and friend" of Sri Lanka.

Pompeo's intentions are quite transparent. They are motivated by obvious geopolitical jealousy rather than a serious concern for the island's interests. Eying American militarization and hegemony of the Indian ocean, Washington wants to pry Sri Lanka away from being a non-aligned country with peaceful ties with Beijing toward being locked in a great power confrontation that will ultimately hurt their interests. Because of the island's strategic location, Sri Lanka is often exceptionally targeted as an example of so-called debt trap diplomacy – a discourse that strives to smear China's overseas investments and the Belt and Road Initiative. But is the claim accurate, and what are the facts? If anything, it's deception from Pompeo.

The term "debt trap diplomacy" was coined by Indian nationalist and anti-China advocate Brahma Chellaney in 2017 and quickly became popular with Western governments and commentators in order to discredit the BRI. It claims that China deliberately overwhelms countries with debt that they cannot repay to gain geopolitical advantages against them.

However, this terminology is a discourse rather than anything empirical; that is, it is a series of beliefs and assumptions which create a narrative. It relies on the prior belief that China's intentions must be bad, zero-sum and, as Pompeo terms it, "predatory." Therefore, they must have a malign purpose behind them, creating a binary that lending and investment practices by Western countries or institutions are always altruistic, benevolent and not profit-driven.

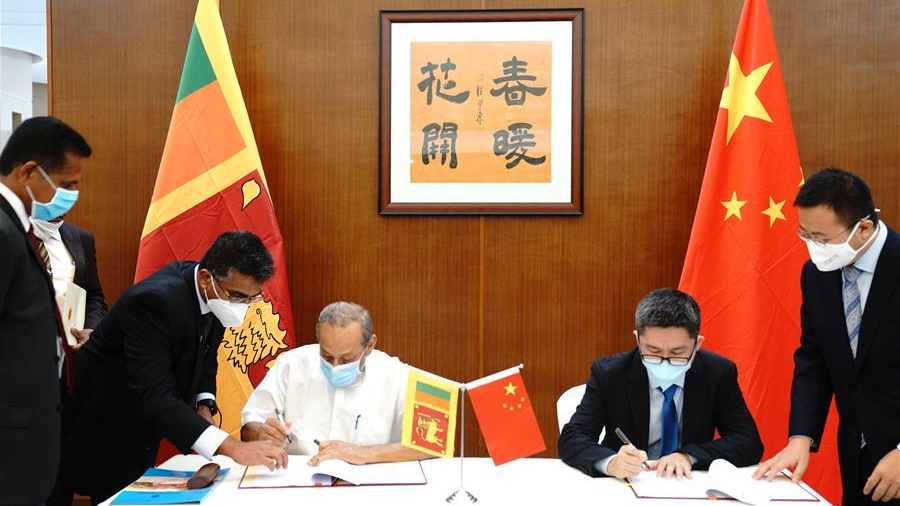

Hu Wei (2nd R), Charge d'affaires of the Chinese Embassy in Sri Lanka, and Vasudeva Nanayakkara (3rd R), Sri Lankan Minister of Water Supply, sign a supplementary agreement in Colombo, capital of Sri Lanka, October 14, 2020. /Xinhua

Hu Wei (2nd R), Charge d'affaires of the Chinese Embassy in Sri Lanka, and Vasudeva Nanayakkara (3rd R), Sri Lankan Minister of Water Supply, sign a supplementary agreement in Colombo, capital of Sri Lanka, October 14, 2020. /Xinhua

Of course, in the case of China and Sri Lanka, there are solid facts to discredit this claim. Writing in The Diplomat last year, analyst Umesh Moramudali set out with data from Sri Lanka's ministry of finance that the "debt trap narrative" owed to China is false. While Sri Lanka indeed has a "foreign debt" problem, it is a structural problem within the country itself, and Beijing does not even come close to being the largest creditor.

As of last year, China holds just 10 percent of Sri Lanka's foreign debt, Japan and the World Bank hold 11 percent each, the Asian Development Bank holds 14 percent, and the private sector holds 39 percent, but this is not the narrative that the Western mainstream media and politicians espouse. They claim Sri Lanka has been inundated by Chinese debt and use the Hambantota port as an example, which is itself misleading, as Sri Lanka hasn't defaulted on its commitments to China and still maintains sovereignty over the port. China doesn't "control" it.

So what is the problem? And why is Sri Lanka such an extensive focus of this misleading discourse? The answer is because it is an important geopolitical location at the heart of the Indian Ocean, and its convenient position links maritime trade routes from East to West.

The United States does not want Sri Lanka's relationship with China to prosper because this may shape global commerce in a way that is unfavorable to the U.S. and thus threaten the "Indo-Pacific" initiative. Therefore, the U.S. wants to provoke anxiety in Sri Lanka and play up the pretentious notion that China constitutes a "predatory threat" despite clear evidence to the contrary. In doing so, it is obvious that the Secretary of State does not have the island's best interests in mind.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)