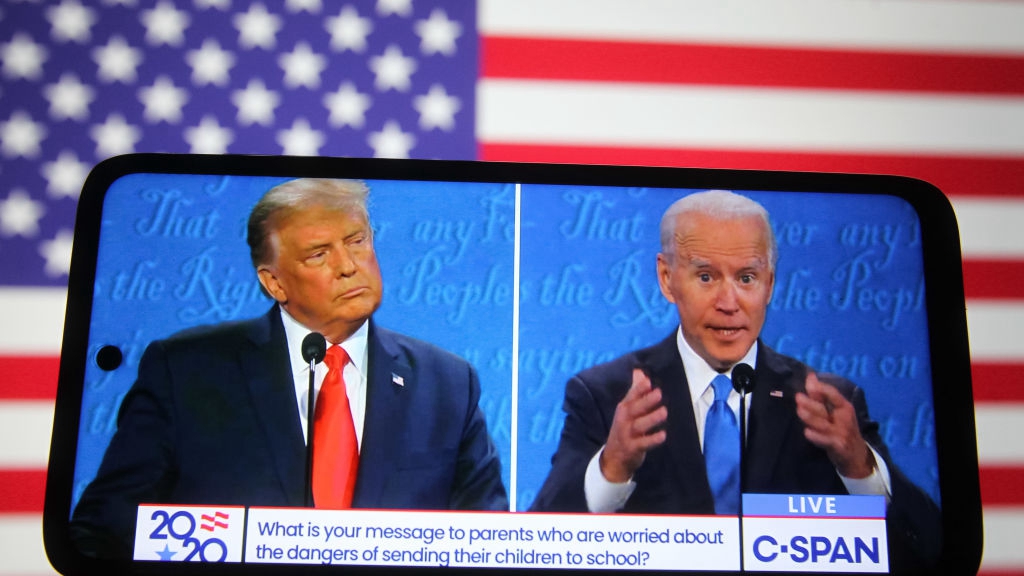

The U.S. President Donald Trump and Democratic presidential candidate and former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden. /Getty Images

The U.S. President Donald Trump and Democratic presidential candidate and former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden. /Getty Images

Editor's note: Chris Hawke is a graduate of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and a journalist who has reported for over two decades from Beijing, New York, the United Nations, Tokyo, Bangkok, Islamabad and Kabul for AP, UPI and CBS. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

On election night in 2000, many Americans were glued to their television screens, watching CBS News anchor Dan Rather declare, "This race must feel like a too small bathing suit on a too long ride back from the beach."

The results hinged on Florida, with Rather noting that the race between the two candidates was "so tight you can't get a cigarette paper between them."

All the major networks were relying on the same data for ballot results, but racing to call the election first. Early in the evening, CBS and the other networks called Florida for Bush. Rather noted, "Bush's lead has melted faster than ice-cream in a microwave."

But then the networks retracted the report, saying the Florida race was still too close to call. Hours later, CBS called Florida for Bush, with Rather confidently announcing, "Sip it, savor it, cup it, underline it, mark it in red, press it in a book, hang it on the wall —George W Bush is the new President of the United States."

Al Gore conceded the election. But then the news networks reversed their forecast again — and Gore called Bush back and retracted his concession. Because of this, Gore looked like a sore loser in the minds of many Americans. This may have influenced Gore's decision to accept the ruling by the Supreme Court that ended the election 36 days later.

News organizations later determined that there was no clear winner in the Florida balloting. The margin was so close, the victor would have been different depending on the method used for counting the ballots. As the world waits again for the results of the U.S. election, it's important to remember that sometimes, the election results simply can't be known on election night, or even for weeks.

U.S. President Donald Trump knows that mail-in ballots are more likely to favor his Democratic rival Joe Biden, and has spent months trying to discredit them, going so far as to sabotage the Postal Service.

This week, Trump has tried a new tactic, the novel suggestion that the results of the election won't be legitimate if they come in after election night. Nate Silver from the polling site FiveThirtyEight.com says there is a 60 percent we will know the results by three a.m. EST — representing a Biden landslide.

Some states, like Florida and North Carolina, allow mail-in ballots to be prepared in advance, and should have final results within hours of the polls closing. If Biden wins either of those states, he has almost certainly won the entire election.

Voters prepare to cast their voting ballot in Tampa, Florida, November 1, 2020. /Getty Images

Voters prepare to cast their voting ballot in Tampa, Florida, November 1, 2020. /Getty Images

Silver gives Trump a 10 percent chance of winning, but says in the case of a close election, it would probably take days or longer to get a definitive result.

Officials in Pennsylvania, the most crucial swing state, have warned most ballots won't be counted until Friday. If the election hinges on Pennsylvania, and the balloting there is controversial or inconclusive, the scenario that has pundits most alarmed would be a Republican attempt to repeat the shenanigans of the 1876 race between Samuel Tilden and Rutherford Hayes.

In 2020, this would play out by Pennsylvania's Republican-controlled legislature using a pretext such as fraudulent mail-in ballots to declare the popular vote inconclusive. The legislature would then send a slate of Republican electors to Washington to choose the president.

This is very unlikely to happen, but a version of this scheme tipped the 1876 election from Tilden, an anti-corruption fighter who won the popular vote, to Hayes.

One thing pollsters can't account for is erratic or unprecedented actions by Trump. For months, Trump has been declaring the 2020 results as fraudulent in advance of the election. Trump has already said that if he does not win, he will not accept the election results.

So how strange will things get when he declares his loss a deep-state scam? Probably Trump will be defeated by such a large margin that his claims of victory will be met with shrug by Democrats and Republicans alike.

However, Trump has encouraged political violence throughout his presidency, and there is no telling what a deranged person or group who believe in race wars or QAnon conspiracies might do. I doubt such violence would matter to the institutions of the U.S. in the long run, even though it may lead to tragic incidents.

That being said, U.S. elections have gotten weird, nasty and violent in the past. The worst example is the 1860 vote won by Abraham Lincoln, whose name was not even on the ballot in 10 Southern states. Lincoln's victory by a plurality led to civil war.

Then there is the deadly feud between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton. The 1800 election, a tie in the Electoral College, ended up being settled in a series of 36 votes in the House of Representatives, with Thomas Jefferson triumphing over Burr. Burr blamed Hamilton for the defeat, and ended up killing Hamilton in a duel.

All of this makes for good Broadway musicals or Netflix dramas. But probably, by the end of Wednesday we will know the winner of election.

After the last four very strange years Trump has given us, I suspect he'll have a surprise or two for us before leaving the White House on January 20. There will probably be Netflix dramas and Broadway musicals based on his presidency. But they probably won't hinge on the question of who won the 2020 election.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)