U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a campaign rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina, U.S., November 2, 2020. /Getty

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a campaign rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina, U.S., November 2, 2020. /Getty

Editor's note: Guy Burton is an adjunct professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

As Americans go to polls today, what will Donald Trump's presidency be remembered for? Much of the media commentary has focused on its style and use of social media, the policies and actions he has taken, and his political support base.

For political scientists, thinking about presidents often involves looking beyond the specifics of an individual office holder.

We're interested in identifying common patterns and themes as well as differences and divergences between them.

Doing this may help identify the broader developments that are taking place and whether the state of political institutions in a country are either stable or in a state of flux. Are they in good health or about to experience change?

Thinking about this was something that I did a few years ago when I published a comparative study of presidents in the U.S. and Latin America with a more senior colleague.

In our book, "Presidential Leadership in the Americas since Independence," we sought to identify the different types of president that have existed in the western hemisphere, so as to evaluate whether they were successful or not.

There are many ways that presidents can be studied, but the method we found most useful was that by the American presidential scholar Stephen Skowronek. Skowronek viewed American political history as cyclical – a concept we applied south of the border as well. While the U.S. political institutions – the constitution, the office of the president, congress, the supreme court – have remained largely unchanged since they were established over 200 years ago, the U.S. has experienced profound social, economic and ideological change.

It has changed from being a predominately rural country to an urban and industrial country today. It has expanded territorially to encompass the continent. It has absorbed diverse ethnic and religious communities beyond its initial white European Protestant base.

It experienced civil war and managed the end of slavery. And in the last century it has seen the expansion of the state, the introduction of civil rights and its global rise to an economic and military superpower.

For Skowronek, presidents who were best able to reflect and represent the changes and demands associated with them and use them to develop new political orders based on them were called reconstructive presidents.

The two most notable examples in the last century were Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan.

Elected just as the country was entering into the Great Depression in the 1930s, Roosevelt expanded the state into the economy and the provision of public services and welfare. By contrast, Reagan came to power in 1980 following criticism of a bloated and inefficient state; he oversaw its retrenchment.

Articulative presidents are those who build on the work done by reconstructive presidents.

All of Reagan's successors, including Bill Clinton, the two Bushes and Obama, might be called articulative in that they did not deviate too far from the model he put in place.

Disjunctive presidents try to keep the current arrangements in place, even as circumstances are changing around them. Jimmy Carter tried to do this with FDR's model in the late 1970s but struggled as the U.S. economy declined.

Finally, preemptive presidents are those who challenge the political system as they find out. They see themselves as a harbinger of change. However, whereas reconstructive presidents are knocking at an open door when it comes to change, preemptive ones are not. They usually end up frustrated, as the system is usually strong and the social and economic forces may be settled.

Our book was published just before the U.S. presidential election in 2016. Because of that, we had no idea how Trump might behave beyond an election campaign, as president.

But based on his rise as a political outsider, winning the Republican nomination and then the election by surprise, we presumed that he would "be a preemptive president, resisting the changes in the political climate."

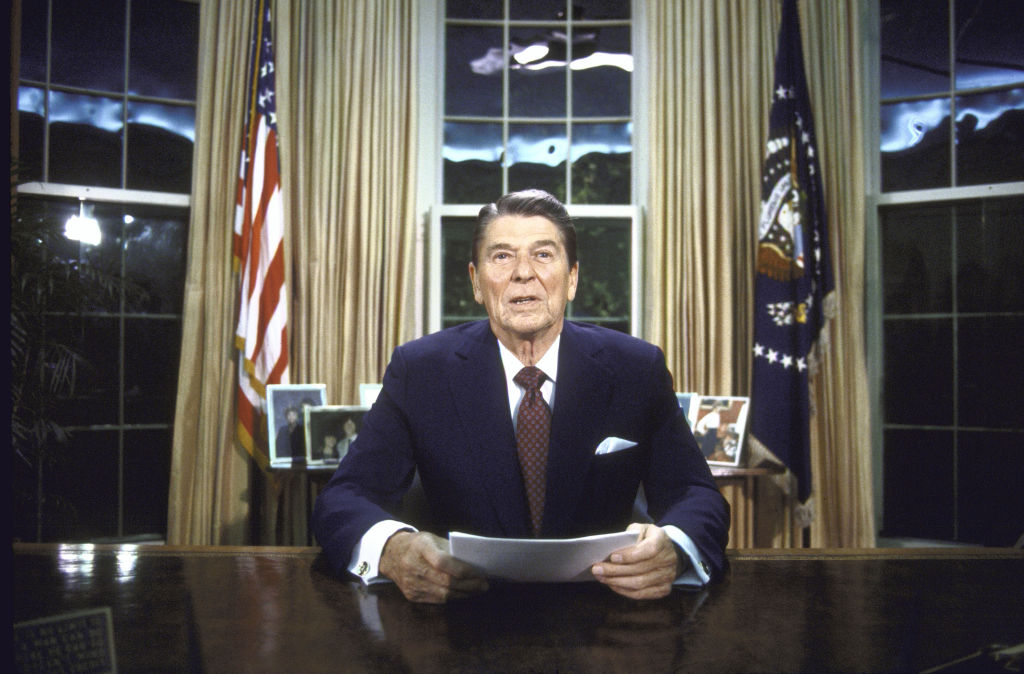

U.S. President Ronald W. Reagan seated at desk in Oval Office. /Getty

U.S. President Ronald W. Reagan seated at desk in Oval Office. /Getty

Since then there have been indications that Trump has fit the model.

On one hand, he has challenged many of the established norms in American politics to the point that some commentators fear the long-term stability of the current political system. His attacks against the establishment may also be seen as an attempt to maintain his status as an outsider.

In part this is helped by his representation of a distinct group of supporters and voters in the Republican party, many of them angry blue-collar white Americans who have lost their jobs and feel overlooked by the two main parties.

On the other hand, Trump hasn't been the wrecker many thought he would be. His tendency to jump from one subject to another and a lack of attention to detail has prevented the political system from being fully tested.

Although he scrapped the healthcare system put in place by his predecessor, he has offered no alternative yet. He has also failed to build more than 640 kilometers of wall along the 2,000-kilometer-long U.S.-Mexican border which he promised.

Another reason that counts against Trump as a preemptive president is that he is not completely against the political system.

Throughout his presidency the Senate has been dominated by the Republicans, who have gladly supported his moves to scrap Obamacare and to introduce tax cuts. Where senators have disagreed with Trump they have kept silent, owing to the extremely high levels of support he enjoys in the party.

In sum then, Trump has proven to be a contradictory figure. But this does not mean that his association with the politics of preemption should be discounted.

Of the four presidential types, Skowronek conceded that the one he had focused least on had been preemptive presidents. Partly, this was because other presidents – especially the reconstructive and articulative ones – had a greater impact and shadow over American politics.

By contrast, preemptive presidents were challengers whose influence cannot be assessed immediately. As a result, preemptive presidents are ambiguous figures: They are unable to make great transformations during their own time in power.

But their significance may lie in them having a preparatory role and laying the groundwork for future change. In the case of Trump, this means that the verdict will be out for at least another president or two has served his or her term of office and the current instability which enabled him to be elected in 2016 turns out to either be temporary or more deep rooted.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)