Editor's note: Hannan Hussain is an assistant researcher at the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and an author. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

For months, Canberra has considered deterioration in China-Australia ties as the result of Beijing's alleged coercion. Yet, it is Australia that had chosen to understate the value of bilateral relations by accusing Beijing of domestic political interference, trade violations, COVID-19 politicization, and cyber espionage.

Despite these frictions, Beijing has constantly prioritized the need for mutual trust, so that Australia could affect a rethink in its hostilities, and revive the foundations of an enduring bilateral relationship. But Canberra's latest prospect of taking Beijing to the World Trade Organization (WTO) over "appropriate" concerns, and its insistence that a China-backed campaign is truly undercutting domestic products, collectively suggests that the desire to ramp-up bilateral tensions is very much active.

"We've reserved our right there [at the WTO], particularly in relation to the instance of barley," warned Australian Trade Minister Simon Birmingham on November 9. "If we have other concerns [about trade with China] along the journey which are appropriate to raise with the WTO, we will do so."

There are several flaws in Birmingham's assertion. First, the Chinese government had communicated the context of Australian barley imports as early as May, clarifying Beijing's review of the commodity as a conventional trade remedy investigation that falls in line with WTO regulations.

Therefore, an attempt to politicize this understanding months later signals Canberra's aversion to bilateral cooperation with Beijing, and risks producing adverse implications for the wider trade volume that sits between both countries.

Second, Birmingham's WTO warning arrives with an important observation: that the alleged China "blanket-ban" on Australian products does not "appear to have materialized" at present. The trade minister also confirmed China's categorical denial of any such ban, adding that several Australian products were actually getting through Chinese customs.

These facts effectively eclipse the case for any sweeping trade "concerns" of Australia that would merit some fruitless, digressive pivot to the WTO in the future. Doing so would not only sidestep bilateral guarantees for "practical cooperation" with Beijing; it would run contrary to the position of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who has upheld the Australia-China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in recent times, and vowed to work closely with industry groups back home for "some clarity" on current concerns.

Last month, the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) released its director sentiment survey, polling over 1,700 senior company executives. The survey found that a quarter of directors believed engagement with Beijing should serve as a key priority for the Morrison government. More importantly, these proponents of Australia-China trade engagement have doubled in size within the last six months.

The findings strike a rare chord with the opposition's own emerging trade narrative on Beijing, arguing that Canberra should address its "failure of trade diplomacy" with China. "The government sounds like a broken record on the relationship with our most significant trading partner: disappointed in events yet failing to set out a plan of how to resolve issues in the mutually beneficial relationship between Australia and China," argued opposition trade spokeswoman Madeleine King recently.

But the central question is will the Morrison leadership embrace these merits on China?

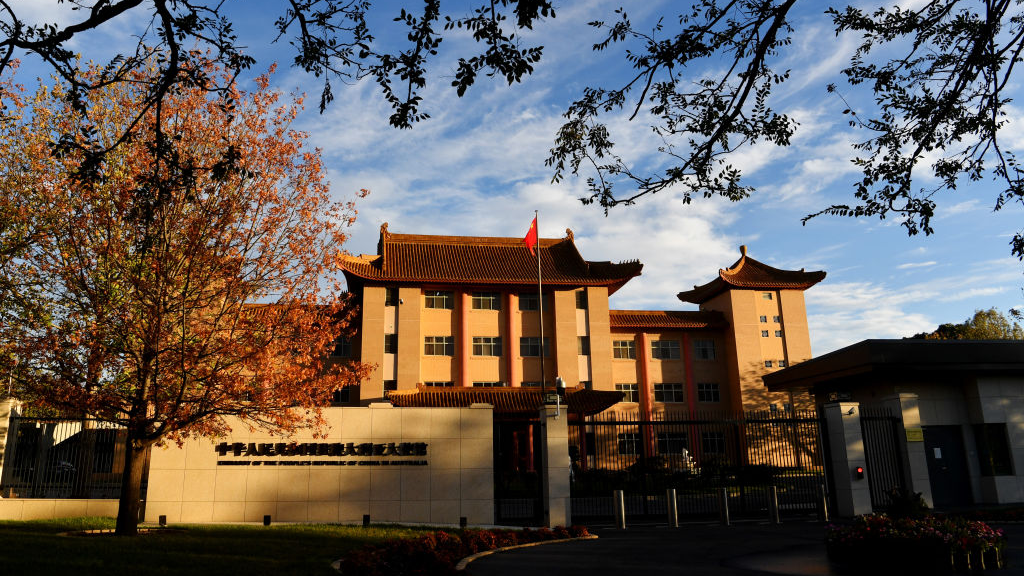

The Embassy of the People's Republic of China is seen in Canberra, Australia, May 12, 2020. /Getty

The Embassy of the People's Republic of China is seen in Canberra, Australia, May 12, 2020. /Getty

His administration appears increasingly reluctant to cede policy space to Australian businesses – crucial stakeholders not resistant to bilateral engagement with Beijing. Government officials have been reviving toxic speculations, such as so-called "informal threats" made by Chinese importers to their exporting counterparts in Australia. Canberra also ruled-out the possibility of short-term rapprochement between Australia and China last week, and instead, "advised" industry representatives to operate within the government's self-identified constraints.

One explanation for a dearth of rapprochement is Australia's consistent determination to interfere in China's internal affairs. Consider the fact that parliamentary inquiries have entertained China's alleged "intimidation and harassment" of the Uygur community. Australia has also stood by its endorsement of flagrant human rights propaganda in China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

This week, implicit opposition to the Hong Kong national security law (NSL) gained new force in the academia, with some Australian universities claiming to "protect" Hong Kong nationals from being allegedly "reported to authorities by their Chinese mainland classmates."

Moreover, the controversial, foreign-funded research institution Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) continues to advertise fabricated reports on China, sustaining a wave of contrarian thinking on Beijing that has driven part of Morrison's own China outlook.

Taken together, it is highly unlikely that Canberra's selective approach to bilateral trade relations would earn credit with Beijing, especially when the latter's sovereign interests are leveraged for political gain. To ensure any pursuit for lasting peace truly prevails with Beijing, it is in Australia's interests to first cap its political overreach vis-à-vis China. Progress on this front will give strength to mutually beneficial diplomacy on all others.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)