Editor's note: Javier Solana, a former EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Secretary-General of NATO, and Foreign Minister of Spain, is currently President of EsadeGeo - Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics and Distinguished Fellow at the Brookings Institution. The article reflects the author's opinions, not necessarily the views of CGTN.

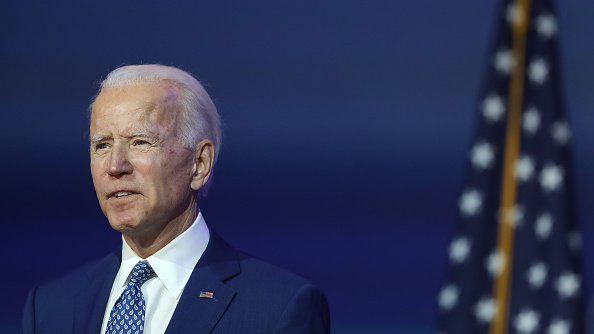

There is an eternal debate about how much leadership and personality matter in international relations. But after the turbulence of the last four years, there can no longer be any doubt that a lot depends on who is at the helm, particularly in the United States. Moreover, as Harvard's Joseph S. Nye convincingly argues – and contrary to what skeptics believe – foreign policy is not devoid of moral considerations. For both these reasons, the election of Joe Biden as America's next president is excellent news for the world.

The American people will, of course, benefit most directly from this turn of events. With his approachable disposition and willingness to engage in dialogue, Biden has devoted his long political career to the essential labor of forging consensus between Democrats and Republicans. Progressives have not always welcomed his flexibility, and his career has not been without blunders. But it is precisely Biden's flexibility that has allowed him to recover from his mistakes and adapt to the times.

The best example of this is his sensible choice of Kamala Harris as his vice president, despite their sharp clashes during the Democratic primaries. Harris's ability to reach out to younger generations will turn into a great asset for the Biden administration.

Progressives should also recognize that Biden's centrist reputation may help him to formulate in a palatable way the profound structural reforms that America needs. In the 1960s, another centrist Democratic president, Lyndon B. Johnson, set in motion one of the most forward-looking social reform agendas in U.S. history.

Biden's problem is that, unlike Johnson, he may well face strong congressional opposition. The Democrats will struggle to win the two run-off votes in Georgia on January 5 that will determine control of the Senate, and the election this month left them with only a slim majority in the House of Representatives.

On top of these difficulties, the ideological gap between Democrats and Republicans has grown in recent decades, hindering bipartisan cooperation and compromise. A recent poll by The Economist and YouGov shows that perceptions on the outcome of the election are heavily dependent on partisan affiliation. While 57 percent of all respondents believe Biden won legitimately, only 16 percent of those who identify themselves as Republican agree.

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (Right) tears her copy of President Donald Trump's State of the Union address after he delivered it to a joint session of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, February 4, 2020. /AP Photo

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (Right) tears her copy of President Donald Trump's State of the Union address after he delivered it to a joint session of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, February 4, 2020. /AP Photo

The Biden administration will face fewer obstacles concerning foreign policy, where U.S. presidents have wider latitude. Furthermore, Biden has worked this terrain for much of his career, first in the Senate, and then during his eight years as vice president under President Barack Obama.

Whereas other members of Obama's cabinet strongly advocated overseas interventions and the use of force, Biden offered a more restrained counterpoint that Obama greatly appreciated. For this and other reasons, Obama never tired of repeating that choosing Biden as his number two was his "single best decision." Moreover, had Biden had his way, the U.S. would not have intervened in Libya in 2011, and Obama would have avoided what he described as the worst mistake of his presidency: letting that country slide into chaos.

Biden's foreign-policy judgment certainly has not been infallible. In 2002, he voted in favor of the Iraq war, while his future boss criticized the decision to go to war as "dumb" and "rash." But Biden acknowledged his error and has made it clear that his administration will shy away from unilateral foreign adventures.

Biden will return diplomacy to its central place in U.S. foreign policy – reviving the battered State Department – and will strongly favor multilateral understandings. His first major foreign-policy decisions will be to rejoin the Paris climate agreement and to halt the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization. In addition, Biden has opened the door to returning to the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement and is expected to adopt a much more constructive position toward the World Trade Organization than that of his predecessor.

Democrats have been fully justified in denouncing the Trump administration's abdication of many of its international responsibilities. But it is neither likely nor desirable that the pendulum swings to the other extreme under Biden. Opinion polls indicate that Americans have little appetite for the U.S. to act as the world's watchdog, although they do want their government to be conscientiously involved in resolving global problems. That is exactly what the rest of the world is asking for: the U.S. is clearly an "indispensable nation," as some like to call it, but it is not the only one.

U.S.-China tensions will persist under a Biden administration, and so will China's rapid economic growth. Despite the ongoing Sino-American trade war during Trump's presidency, China continued to grow by more than 6 percent annually until the COVID-19 pandemic, and the International Monetary Fund expects that it will be the only major economy to expand in this disastrous year. Biden will have to find ways to cooperate with a country that simply can't be shunned.

In that task, he will be able to rely on the European Union, whose recently developed "dual approach" to China openly recognizes the existence of deep disagreements but also acknowledges coinciding interests. The EU will also apply this moderation (albeit a warmer version of it) to transatlantic relations, forging tight bonds with the Biden administration without diminishing the strategic autonomy that the bloc has been trying to consolidate.

When Biden pledged during his presidential campaign to "build back better," he wanted to emphasize that his economic plan involved tackling long-simmering structural problems rather than taking the U.S. back to 2016. A similar logic applies to foreign policy, where the U.S. urgently needs to reinvent its international role.

Doing this successfully will require an empathetic leader like Biden, who has always taken pride in his ability to navigate sensitive issues. After having underestimated him too often, his detractors must now at least admit that he has earned the opportunity to surprise them.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2020.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)