National flags of Iran and the U.S. /Reuters

National flags of Iran and the U.S. /Reuters

Just when Joe Biden's electoral victory raised the prospect of a U.S. return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), events have taken a dramatic turn after Iran's top nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was assassinated. Not only the incoming Biden administration will face a slew of more problems that may dampen its diplomatic outreach, but Iran, which has high hopes for a nuclear deal revival, is also finding itself hard to reconcile with the aftermath.

Though unclear which party carried out the killing, a prevailing media speculation is that Israel, the biggest opponent to the nuclear deal that the outgoing U.S. president scrapped in 2018, was the one responsible. It is suspected that Israel had one goal in mind when it presumably made that decision – to block a U.S. reentry into the agreement.

"It is pretty certain that Israel carried out the assassination. I believe that Israel wanted to put Biden in a difficult situation since the killing raised the issue of Fakhrizadeh's activities while the JCPOA had been in effect," Meir Litvak, chair of the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University, told CGTN.

Presumably the official most capable of shifting Iran's civilian nuclear program to one that manufactures bombs, Fakhrizadeh is believed to have led a covert program that Tehran allegedly established in 1989 to carry out research on a potential nuclear bomb. Though the project was believed to be shut down more than a decade ago, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said in 2018 that documents obtained by his country showed Fakhrizadeh was secretly running another project with a similar aim.

If true, these activities would have been a direct violation of the JCPOA as this type of nuclear ambition was explicitly forbidden under its terms. But ever since the Trump administration's withdrawal from the deal, its maximum pressure campaign against the Islamic Republic has overshadowed the implications of the potential breach. Now that the point man allegedly responsible for Iran's weakened credibility is dead, the revival of discussions on the issue could complicate Biden's expected return to the negotiation table.

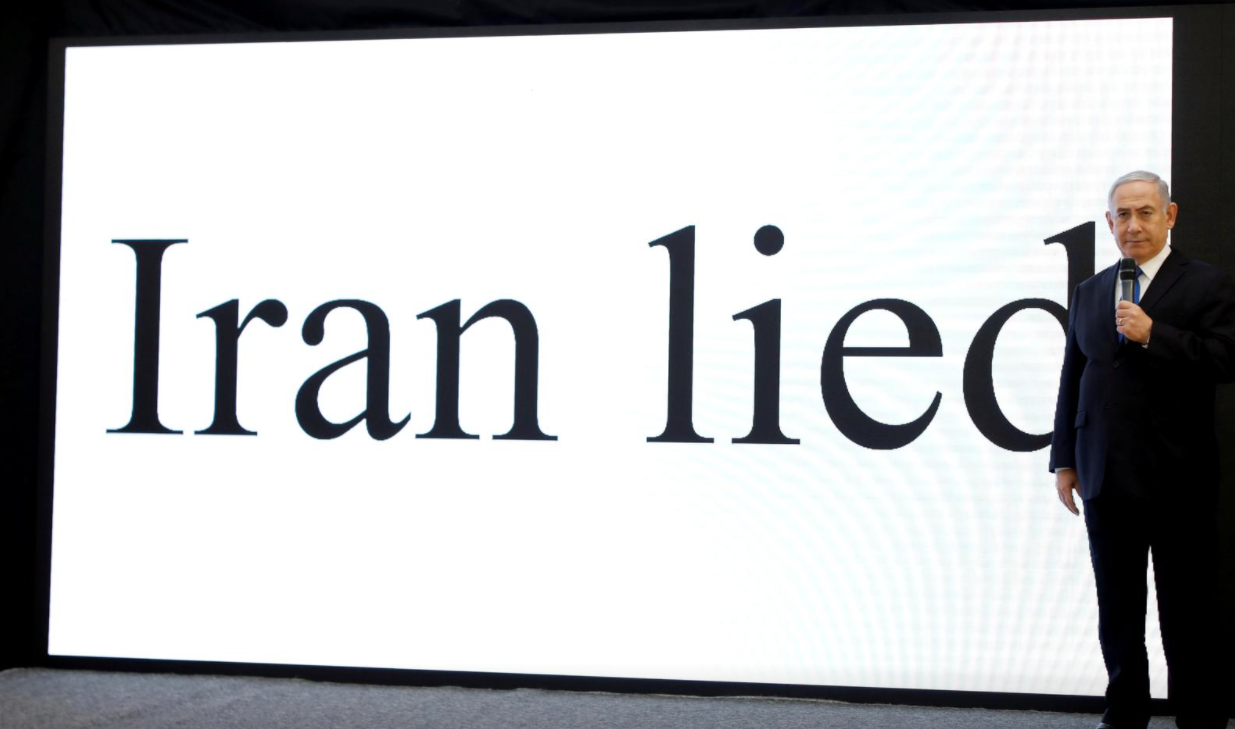

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gives an English presentation claiming Iran was secretly running a nuclear project, May 2018. /Reuters

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gives an English presentation claiming Iran was secretly running a nuclear project, May 2018. /Reuters

But that's not all. The assassination-triggered responses in Iran, especially those from the hawkish camp, are further restraining Biden's hands. Reacting to the scientist's death, Iran's hardliner-dominated parliament approved a bill on Tuesday that would suspend U.N. inspections of its nuclear facilities and require the government to boost its uranium enrichment if European signatories to the nuclear deal do not provide relief from oil and banking sanctions. And since Iran has already enriched uranium to the tune of 12 times more than what's permitted under the JCPOA, the U.S. president-elect is faced with a growing list of difficulties in the event of a sit-down with his Iranian counterpart.

It won't be easy for Biden to appease elements of domestic opposition if he can't make Iran return to its pre-withdrawal conditions when entering a new agreement, Litvak said.

U.S. President-Elect Joe Biden speaks at the theater serving as his transition headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware, U.S., December 1, 2020. /Reuters

U.S. President-Elect Joe Biden speaks at the theater serving as his transition headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware, U.S., December 1, 2020. /Reuters

As for the Iranian side, the situation could be equally complicated.

"No matter how desperate a Biden administration may be for a deal, it will be Iran's response that will matter more," Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, told CNBC before Fakhrizadeh was killed. That argument was made largely based on the expectation that Iran will be asking the U.S. to compensate its economic losses induced by Trump's sanctions.

With the shadow of the assassination now casting over the proud nation, the significance of Iran's response has been magnified.

So far, Tehran has made it clear that its resolve to begin negotiations with the incoming Biden administration will not be affected by the incident, but the administrative branch led by President Hassan Rouhani does not have the final say on nuclear policies, which is rendering a future rapprochement with less certainties.

The free rein Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is giving Rouhani on the matter is "very little, and the necessary minimum," Litvak said. "The president can try to convince him to take a more flexible or tougher line, but he is the one who makes the decision."

A zealous advocate of the JCPOA, Rouhani has been the subject of constant criticism from Iran's hardliners ever since the agreement was signed, and Trump's abandonment of it gave his opponents even more ground to attack him. Khamenei, who voiced his reservations from the very start, has since repeated the idea that the U.S. could no longer be trusted. Just days before the assassination took place, he dismissed the prospect of new negotiations with the West. "We once tried the path of having the sanctions lifted and negotiated several years, but this got us nowhere," he said.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (C) and his cabinet meet Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (1st L) in Tehran, Iran, August 29, 2018. /Reuters

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (C) and his cabinet meet Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (1st L) in Tehran, Iran, August 29, 2018. /Reuters

Still, it is unlikely the supreme leader will actually block Rouhani's anticipated talks with Biden. "After all, the signing of the nuclear deal received Khamenei's endorsement even though he remained skeptical," Lu Jin, a research fellow at the Institute of West-Asia and African Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told CGTN. "In contrast to the hawkish camp, Khamenei and other clerical leaders including Ebrahim Raisi, the head of Iran's judiciary and a prospective candidate to succeed the supreme leader, have also remained discreet in their reaction."

"They are weighing the country's public opinion on the matter," she added. "On the one hand, the Iranian people have suffered tremendously under the harsh sanctions and are anxiously waiting for the U.S.' transition period to end. On the other hand, the distrust toward the U.S. fueled by its JCPOA withdrawal is propelling the clerical leadership to avoid another embarrassment."

In a statement last week, Khamenei explicitly called for revenge for the slain scientist, but shunned away from making threats comparable to those after Qasem Soleimani was killed in a U.S. drone strike. Missing in the tweet where his statement is documented is the hashtag "#SevereRevenge," which he used in the wake of the general's death.

"That the supreme leader has restrained from speaking on terms beyond the scope of the matter is indication that he wants to maintain peace with the U.S. and in the meantime try not to kill off the prospect of re-engagement with Washington on the nuclear deal," Lu said.

While Khamenei's discretion leaves room for imagination, there are limitations in his acquiescence. "If Iran does go back to negotiations with the U.S., Khamenei will seek to make sure that Rouhani will not make any serious concessions," Litvak said.

But since the fallout of the assassination is inevitably pushing Biden to a position where he will have to ask Iran for more concessions, and since Iran has not changed its position on U.S. compensation, the hopes of the two sides meeting halfway have been much restricted, Lu added.