For decades, conservative politicians in the West have pushed for cutting taxes for the wealthy. While the idea of reducing taxes to boost the economy has existed for at least a century, it didn't come to full blossom until the 1980s when neoliberalism and free-market economics took the Western political scene by storm.

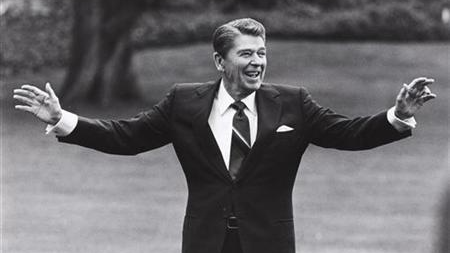

In August 1981, then U.S. president and conservative icon Ronald Reagan enacted the "Kemp-Roth Tax Cuts" – known as the largest of its kind in history – seven months after taking office. Over his two terms, Reagan pursued a series of neoliberal policies that fulfilled the wildest dreams of America's rich elite, including slashing the federal income tax, capital gains tax and loosening government regulations on businesses.

"Government is not the solution to our problems, government is the problem," Reagan famously declared in his inaugural address.

Meanwhile on the other side of the Atlantic, the British government under Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher crushed trade unions, reduced taxes and privatized industries. The neoliberal golden age culminated when British Chancellor Nigel Lawson introduced the 1988 Budget – a tour de force in slashing taxes including corporation and inheritance taxes that overwhelmingly benefited the wealthiest people in the UK.

President Ronald Reagan waves to well-wishers on the south lawn of the White House, April 25, 1986. /Reuters

President Ronald Reagan waves to well-wishers on the south lawn of the White House, April 25, 1986. /Reuters

Rationale for these tax reductions is simple: More money saved at the top would trickle down to everyone else in the form of business investments which would in turn stimulate economic growth. In the end, everyone would be better off when the rich could save up.

However, the latest study from the London School of Economics (LSE) confirmed what many critics of the theory have long suspected – the money saved at the top never came down. The new study, published by the International Inequalities Institute at LSE, looked into the macroeconomic implications of tax cuts for the rich in 18 developed countries over a 50-year period, from 1965 to 2015.

Using a unique metric, researchers Julian Limberg and David Hope compared countries that passed tax cuts in a specific year with those that didn't. They found "strong evidence" that cutting taxes on the rich didn't accomplish anything except helping them stay rich. Contrary to the belief that tax cut reduces unemployment and boosts economic productivity as many supply-side economics believe, the study found no evidence that supported those claims.

"Overall, our analysis finds strong evidence that cutting taxes on the rich increases income inequality but has no effect on growth or unemployment," the study reads. "Our findings on the effects of growth and unemployment provide evidence against supply-side theories that suggest lower taxes on the rich will induce labor supply responses from high-income individuals that boost economic activity."

The report also echoes the work of French economist Thomas Piketty, whose 2013 global bestseller "Capital in the 21st Century" helped put income inequality at the center of the current economic debate. After analyzing the effects of tax cuts in Europe and the U.S. over the past two centuries, the economist found that big tax cutters like the U.S. did not grow any faster than countries like Denmark, which kept taxes high.

Jeff Bezos could give every Amazon employee $105,000 and still be as rich as he was before the pandemic, American economist Robert Reich wrote on Twitter. /Reuters

Jeff Bezos could give every Amazon employee $105,000 and still be as rich as he was before the pandemic, American economist Robert Reich wrote on Twitter. /Reuters

What tax cuts did trigger was a sharp increase in wealth for the top 1 percent. The findings also suggest that lowered tax rates encouraged corporate executives and other top earners to game the system at the expense of everyone else.

"Our results are in line with those in Piketty et al, which suggest that lower taxes on the rich encourage high earners to bargain more forcefully to increase their own compensation, at the direct expense of those lower down the income distribution," the LSE study notes.

The only way to reverse the rapidly growing wealth inequality, Piketty concluded, is through imposing a global wealth tax combined with an 80-percent progressive income tax targeted at the world's super rich. Implementing those measures, however, would be technically difficult and politically impossible, as the economist himself acknowledged.

The pie gets smaller for the poor

"Where we are today in the 21st century, a basic middle class life is not accessible to very large portions of America," said Nobel Prize laureate and professor at Columbia University Joseph Stiglitz during a discussion organized by the school in September.

In 2019, income inequality in the United States reached its highest level in 50 years. Wealth for the top one percent ballooned under U.S. President Donald Trump, whose signature tax reduction plan known as "Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017" cut the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent.

A homeless woman sits on a bench few blocks away from the White House in downtown Washington, September 1, 2015. /Reuters

A homeless woman sits on a bench few blocks away from the White House in downtown Washington, September 1, 2015. /Reuters

Instead of helping raise the income of workers, as promised by the Trump administration, the money lined up in the pockets of corporate executives. According to an analysis of Fortune 500 companies by the International Monetary Fund, 80 percent of the windfall corporate tax cuts went to wealthy investors who hold a vast majority of corporate stocks in the form of dividends and buybacks. A mere 20 percent was spent on activities that would boost economic productivity, such as increasing capital expenditures or research and development.

Millennials in the U.S. controlled just 4.6 percent of the total wealth of the U.S. population through the first half of 2020, despite making up the largest portion of the workforce in the country, according to data compiled by the Federal Reserve. In comparison, baby boomers born after WWII held 53 percent of the country's wealth, while Gen X accounted for over 25 percent, and the silent generation nearly 17 percent.

"Young people aren't going broke because they're buying avocado toast. They're going broke because the economy is rigged against them," American economist Robert Reich wrote on Twitter.

(Cover image by Li Jingjie)