An armed simpleton who invades a pizza restaurant to break up an imaginary pedophile ring he read about online is a national punchline.

Thousands of armed believers launching a deadly attack on Congress is a national security threat.

The mob that stormed Congress on January 6 was not simply whipped into a frenzy by President Donald Trump's speech in front of the White House earlier that day.

Rather, the participants had coalesced over time around conspiracies alleging a Democratic child sex ring and mass election fraud, and started organizing online in December, after the president had started hyping the rally, tweeting to followers, "Be there, will be wild!"

The violence that ensued was organized online, complete with GoFundMe pages and advice to bring zip ties and weapons to arrest lawmakers – or rope to hang them.

Calls for violence occurred on mainstream sites like Twitter and TikTok. On niche web sites and platforms like Parler and Gab, people talked in detail about plans to violently storm the Capitol.

Insurrectionists are continuing their online planning. Some have called for an armed march on all U.S. state capitols on January 17. There are calls for a Million Militia March in Washington on January 20, the day of President-elect Joe Biden's inauguration.

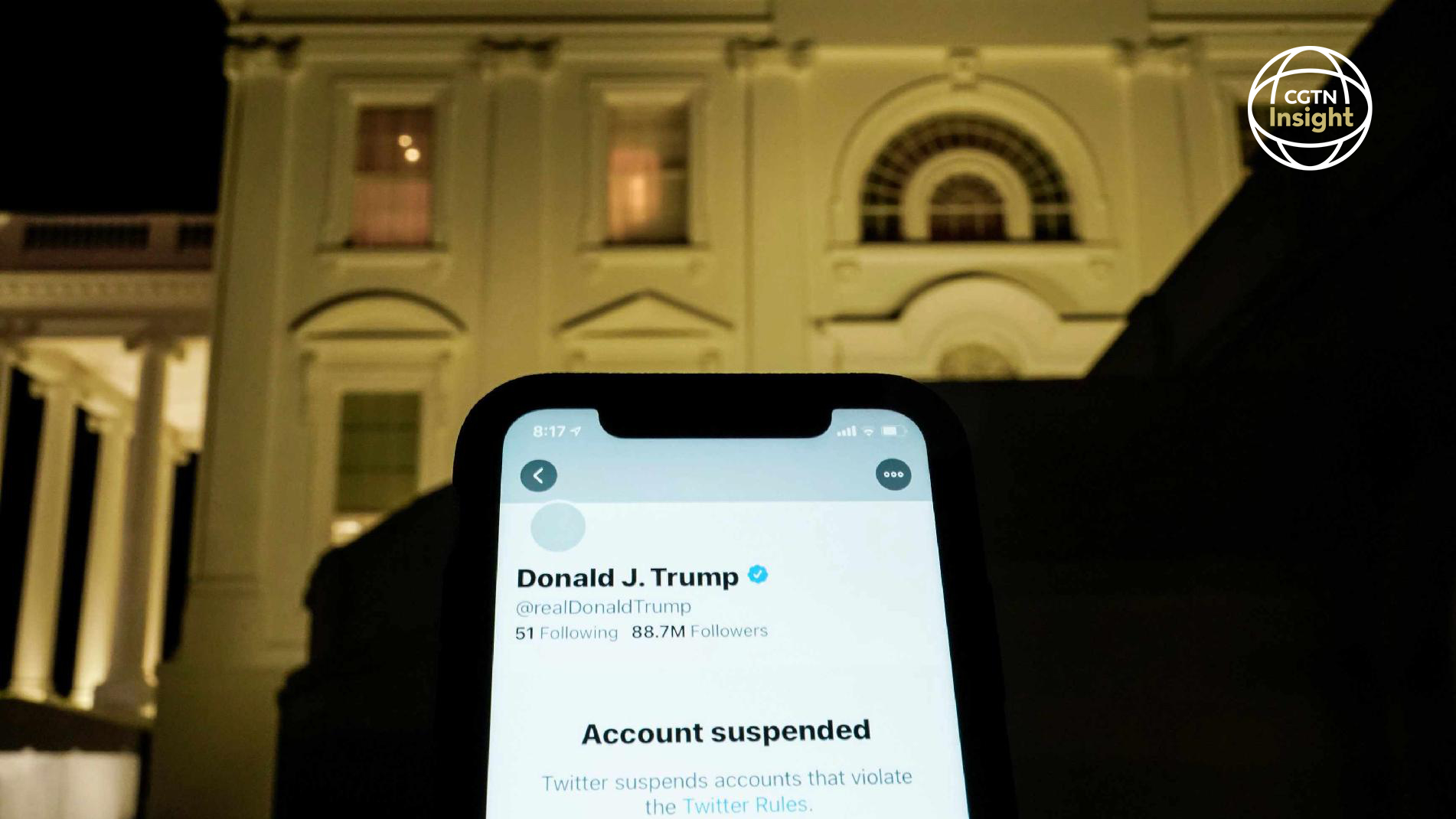

In response to the looming storm, Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms have banned Trump. The right wing social media platform Parler has been driven offline for the time being.

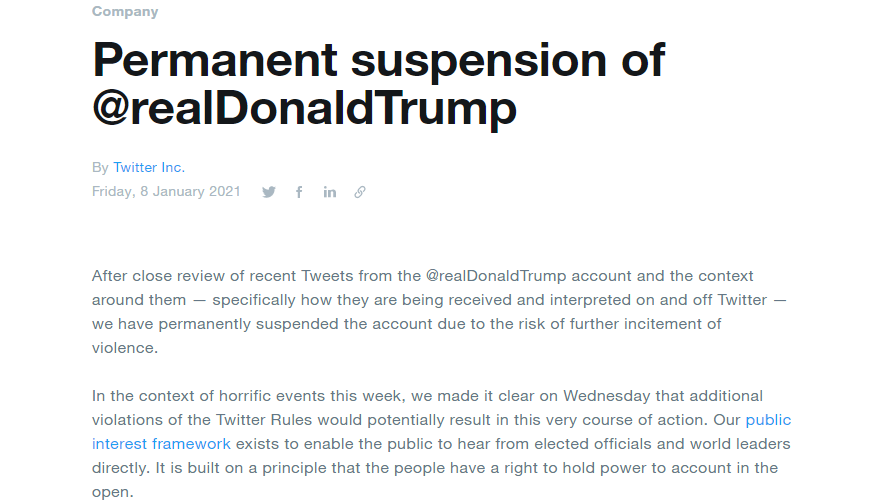

Screenshot of an official blog post by Twitter explaining the reason for the suspension of U.S. President Donald Trump's Twitter account.

Screenshot of an official blog post by Twitter explaining the reason for the suspension of U.S. President Donald Trump's Twitter account.

These responses seem like applying a band-aid to a bullet wound.

First, they won't work. If U.S. authorities are incapable of acting on danger signs posted on Facebook, will banning Trump and closing one of many social media platforms improve their capability?

This leads to the second problem. Big tech corporations have chosen to ban Trump and Parler to solve public relations problems and protect their shareholders.

They don't care about online extremism, because until now it has not been a threat to their bottom line.

As part of Trump's feud with big tech, the outgoing president and his allies want to revoke the law known as Section 230, which protects internet companies from being liable for content published by a third party.

The aspect of this law that the right wing dislikes protects tech companies from getting into trouble for the political decisions behind their moderation decisions.

Many right-wingers want content on the internet to be unregulated unless it violates a law. In this view, hate speech, which is legal in the U.S., could not be banned by a company like Facebook.

However, more generally, Section 230 also removes any liability for extremist content, making it safe for big tech to allow people to advocate views that could hurt society or lead to violence to flourish.

This protection from liability is why big tech is not particularly worried about its impact on U.S. national security. This was highlighted by the response to threat of alleged foreign interference in national elections – first ignoring it, then doing as little as possible.

This is also why tech companies make a big deal of banning Trump, but take no responsibility for fomenting the January 6 violence, and no substantive action to prevent it from happening again.

Exceptions to Section 230 have been carved out for child exploitation and prostitution. So why hasn't Section 230 been revised to hold big tech responsible for allowing calls for violent extremism?

The prosaic answer is that this kind of moderation would cost a lot of money and hurt tech companies' bottom line. More broadly, this could push Big Tech into shortcuts and workarounds that would chill free speech, raising First Amendment issues.

As the threat to the U.S. government changes from an abstraction to attacks being planned for later to this month, the rules around online content are dangerously broken, with no fix in sight.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)