In August 2020, thousands of Whatley Bridge residents in the UK were evacuated as an aging dam built in 1831 started collapsing. The crisis unfolded as the country was battling to control the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Such emergencies could occur at any of the 58,700 large dams worldwide. These dams, constructed between 1930 and 1970, have crossed their designed lifespan of 50 to 100 years, putting millions of people living downstream at risk of flooding, warned a United Nations University's Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-IWEH) report on Friday.

The mammoth concrete structures were built on major rivers to store water, generate hydropower, irrigate fields, and prevent floods. But they have become problems as governments have failed to come up with plans to tear down old dams sustainably.

"This problem of aging large dams today confronts a relatively small number of countries – 93 percent of all the world's large dams are located in just 25 nations," said Duminda Perera, lead author of the report.

The situation is particularly alarming in four Asian countries – China, India, Japan, and South Korea – that have nearly 55 percent or 32,716 of the world's large dams. A majority of these structures will reach the 50-year threshold soon, as with many large dams in Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe in the coming years.

Climate change-triggered extreme weather events are further weakening the structural integrity of old dams. In 2017, Hurricane Maria, with a speed of 280km/h, damaged the 90-year-old Guajataca dam in Puerto Rico, forcing the evacuation of 70,000 residents.

"Rising frequency and severity of flooding and other extreme environmental events can overwhelm a dam's design limits and accelerate a dam's aging process," said Vladimir Smakhtin, director of the UNU-INWEH.

The amount of water held by dams is staggering. These concrete walls hold an estimated 7,000 to 8,300 cubic kilometers of water – enough to cover about 80 percent of Canada's landmass under a meter, the report calculated.

Large dams above 15 meters in height, according to experts, are also known for causing severe environmental damage by disrupting aquatic creatures' migration routes. And a rising level of sediments caused by the deposition of silt brought by strong water currents has continually raised dam maintenance cost.

Can aging dams be removed to restore the river ecology and ensure public safety?

Public safety, escalating maintenance costs, reservoir sedimentation, and restoration of a natural river ecosystem have become driving factors behind dam decommissioning, said the report.

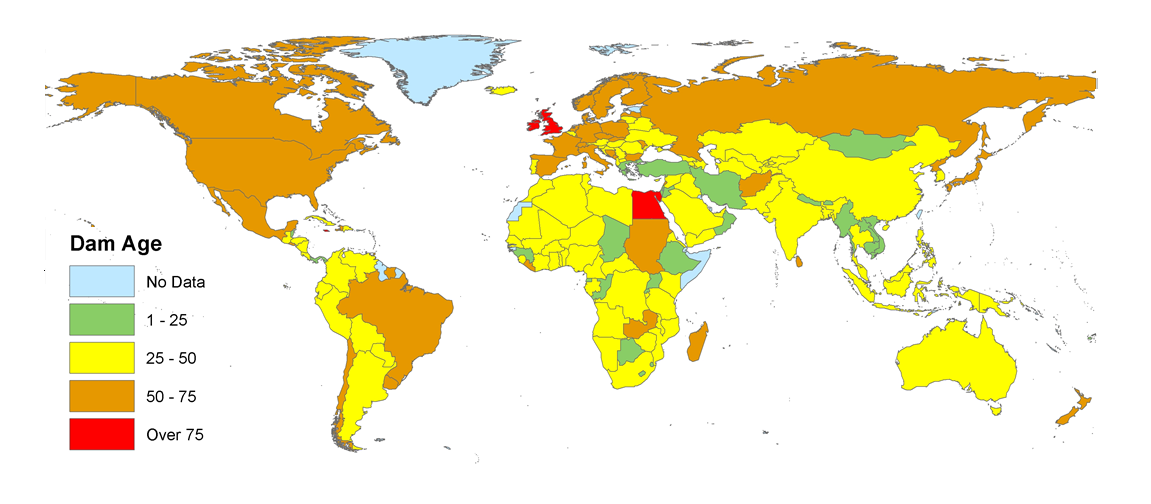

The average age of large dams by country. /Data source: ICOLD WRD, 2020

The average age of large dams by country. /Data source: ICOLD WRD, 2020

But such decommissioning, removing the dam wholly or partially, is happening at a snail's pace. While many countries are consulting experts to initiate the process of removing old dams, the concept is "still in its infancy," with only a few dams removed in the last decade.

However, removing a dam structure also has an array of economic, social, and ecological impacts depending on the local geography. "A few case studies of aging and decommissioned large dams illustrate the complexity and length of the process that is often necessary to orchestrate the dam removal safely," said R. Allen Curry, adjunct professor, UNU-INWEH.

"Even removing a small dam requires years (often decades) of continuous expert and public involvement and lengthy regulatory reviews. With the massaging of dams well underway, it is important to develop a framework of protocols that will guide and accelerate the dam removal process," he added.

Despite prevailing challenges, the U.S. has emerged as a dam decommissioning leader, removing around 1,275 dams in 21 states over the last 30 years. The country dismantled 80 dams removed in 2017, the report said.

Dam decommissioning should be seen as equally important as dam building in the overall planning process on water storage infrastructure developments, suggested the report.

"Decommissioning may be more economical than repair of a dam," Duminda Perera and Vladimir Smakhtin, authors of the report, told CGTN.

But this is mostly true for North America and Europe. "In the Asian context, the situation may be different. Financial and technical strength are the two determinant factors to be considered critically in a dam decommissioning. Developed and developing nations might take different alternative ways to deal with ageing dams," they said.

(Cover: Glines Canyon Dam on the Elwha River during the dam removal process. /USGS)