Donald Trump gives a final fist pump as he boards Marine One departing the White House in Washington, D.C., January 20, 2020. /Getty

Donald Trump gives a final fist pump as he boards Marine One departing the White House in Washington, D.C., January 20, 2020. /Getty

Editor's note: Hannan Hussain is a foreign affairs commentator and author. He is a Fulbright recipient at the University of Maryland, the U.S., and a former assistant researcher at the Islamabad Policy Research Institute. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Former U.S. President Donald Trump's relevance to contemporary U.S. politics, by authority, is history. But his ironclad grip on white nationalism is enough to incentivize an unprecedented second impeachment trial in the U.S. Senate, scheduled for February 9.

The process leading up to this date has important lessons for Democrats, and the challenges they may face in pushing Republican support behind impeaching Trump. Top Republican Senator Mitch McConnell is arguably the most satisfied with this weeks-long delay. He made it a central theme of his standoff with the Democrats in the senate to cede space to a tactical interval, under the garb of a free and fair trial. The end result: he succeeded.

Second, all of this noise about Trump's legal team getting sufficient time to prepare for the trial is a bluster. The former president predetermined the type of legal representation he took to be best suited to the upper chamber. He chose his attorney from Lindsey Graham's recommendation handbook. Graham, a longtime Trump loyalist and one of the jurors to serve on the trial, gave Trump's attorney a nod as his personal recommendation.

Meanwhile, Republicans appear to have given Senate Democrats the impression that the delayed date "is a win" as it encourages senate confirmation of President Joe Biden's cabinet, and may limit opposition to his $1.9 trillion COVID-19 stimulus package.

If that is to be taken at face value, there is little to explain why Biden has been compelled to sign two executive orders to boost economic relief for Americans during COVID-19, when early republican opposition to the $1.9-trillion package remains well in-tact. Moreover, Biden's underlying rationale on the executive actions – that "we cannot, will not let people go hungry" – is still read by the republicans as lavish spending. How exactly is a delayed impeachment trial challenging this dynamic at present? No reasonable indication.

In a similar spirit, pushing Trump's impeachment trial to early February – instead of next week – extends marginal, not significant support, to Biden's cabinet confirmation progress. This is because senate republicans, who chair key committees, have scheduled cabinet hearings without guaranteeing headway on Trump's impeachment date. The end result is a toss-up between choosing one over the other – classic republican doublespeak that may prove difficult to transform by February 9.

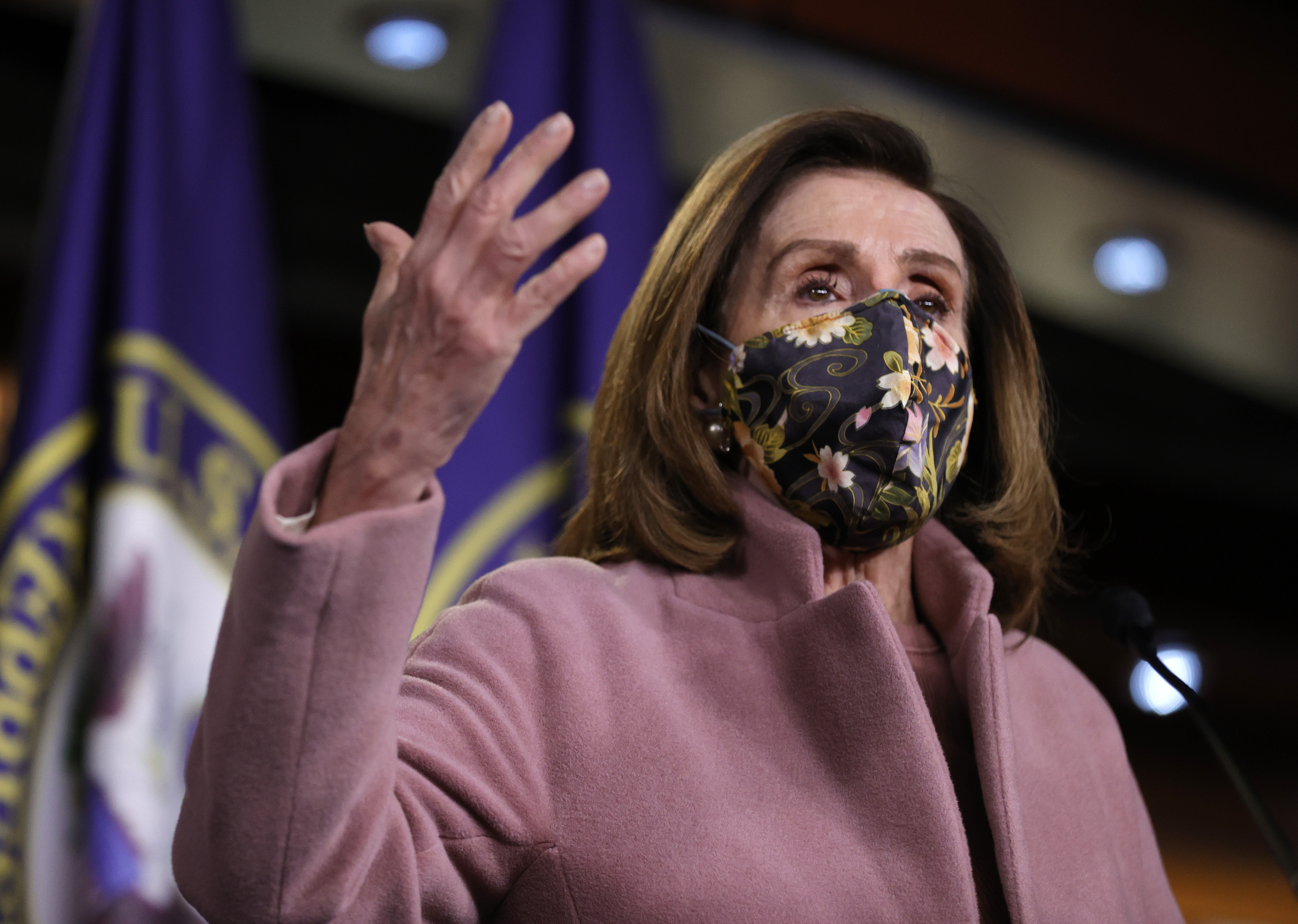

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi speaks during her first weekly news conference under the new Biden administration in Washington, D.C., January 21, 2021. /Getty

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi speaks during her first weekly news conference under the new Biden administration in Washington, D.C., January 21, 2021. /Getty

In a welcome move, U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi prepared the ground for the article of impeachment against Trump to be sent to the Senate on January 25, on "incitement of insurrection" grounds. "Exactly one week after the attack on the Capitol to undermine the integrity of our democracy, a bipartisan vote of the House of Representatives passed the article of impeachment, which is our solemn duty to deliver to the Senate," said Pelosi in a statement on January 22.

Should the article have reached the upper chamber on January 25 without the February 9 deal with McConnell, it would have automatically necessitated Trump's senate trial. But even before democratic initiative on impeachment gathered steam, republican actions continued to indicate a conscious disengagement from the immediacy of the hearing.

Look no further than top senate leaders choosing to confine Trump's conviction to behind-the-scenes discussions, harboring ambitions "to acquit" a president that has brought his own party on the verge of significant public skepticism.

Most tellingly of all is a "move-on attitude" among scores of republicans, vis-à-vis Trump's incitement of the Capitol riot. It is a known fact that endorsing the January 6 violence, weeks away from a set impeachment trial, has proven a risky gamble for several republicans. But judging by recent memory, all it took were ten representatives from within GOP ranks to stand with democrats, and impeach Trump by a 232-197 vote margin in the House recently. It was ruled as the most "bipartisan impeachment vote in history."

What democrats would be vying to achieve next month is an additional seven republicans to that "historic" 10-member bipartisan tally – a far cry considering that dozens of GOP members are refusing to acknowledge democratic activism on the process of accountability.

Together, the Republican Party applies a two-track approach to impeaching Trump, even when their top senate member has successfully earned a buffer-period for the trial next month.

This two-track approach comprises of a supportive GOP fringe on the one hand (easier to win-over, but less effective in the final impeachment tally for democrats). The second element is the Republican Party's internal neutrality on impeachment, driven by a more significant consensus: to head into the impeachment trial, but avoid broad-based advocacy if it means confirming democratic optimism at the peak of the Democrats' era.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)