More often than not, children and young people fall victim to the systems they live in. Their voices and opinions are dismissed and lost in a vacuum of political decision-making for a world everyone say they will in the future lead. To try and change this, the European Commission initiated a survey alongside five Children’s Rights organizations to understand young people and help inform the EU's Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the Child Guarantee.

“Our Europe. Our Rights. Our Future” is the result of that survey to more than 10,000 children, between 11 and 17 years old from within and outside Europe and hopes to be a “game-changer … and an important step towards greater child participation,” said European Commission Vice-President, Dubravka Šuica.

Covering health, education, rights and participation, the survey from ChildFund Alliance, Eurochild, Save The Children, UNICEF and World Vision found that mental health issues appear as “a widespread and significant concern,” with one in five participants revealing they feel sad or unhappy most of the time.

“Almost 1 in 10 respondents from the EU identifies as living with mental health problems or symptoms such as depression or anxiety, with girls far more at risk than boys, and older children reporting higher levels of problems than younger children,” the report added.

Data speaks even louder when it comes to minority groups. Nearly half of LGBTQ+ children and a third of children with disabilities admitted feeling sad or unhappy most of the time.

Anxiety about the future, bullying and challenges in coping with school are some of the causes for “these alarming rates of mental health problems.” Children in the wider European region feel more anxious about their families.

COVID-19 might have made this issue worse. Participants stressed, “missing their friends during lockdowns, being bored, missing their teachers (particularly young children), stress related to money, conflict with parents and family members, mental health problems, fear about getting behind in studies and about the future.”

Discrimination awareness

One of other worrying findings was that one in three children in the EU have experienced some form of differential treatment. In addition, girls were far more likely to feel they were not being treated equally.

“I can say that I am treated differently, for example, it is a gender stereotype, only because I am a girl. Me and also other girls feel oppressed or different from boys, who are adored unconditionally,” said a 15-year-old girl from Albania in the report.

On the issue of discrimination and exclusion, the survey also found that more than half of children with disabilities (physical, intellectual, sensory or autism) or migrants, asylum seekers, ethnic minorities or identifying as LGBTQ+ have experienced some form of differential treatment.

“I was with some friends, I told them that I was Roma, and they were shocked, they didn't believe it, because they thought that Roma do nothing, and behave badly. And since I'm a good person, they didn't think I was a Roma,” a Roma boy aged 13 from Spain said in the report.

For the organizations, the results show “keen sensitivity among the respondents towards issues of discrimination, even if they themselves do not experience it.”

Read more: 'Human tragedy': Children constitute 34% of human trafficking victims worldwide

Schools don’t meet the needs of 21st century children

As places where young people spend most of their time, schools surfaced not as a safe environment, but as a discrimination ground. Bullying from teachers and students were concerns raised but the respondents.

Although most of the children surveyed (nearly three quarters) felt positive about the school, there is a marked trend indicating that as they grow older, children tend to feel that school doesn’t prepare them well for the future. Friendships are seen as the most valuable aspect, while curriculum content and culture are less rewarding.

“The findings strongly suggest that school systems do not sufficiently meet the needs of children in the 21st century,” the study stated, noting that the majority of the respondents would like to make changes to school life. If they could choose, they would have more sports activities, art subjects, more interesting lessons, less homework and even classes on child’s rights.

Screenshot of “Our Europe. Our Rights. Our Future” report.

Screenshot of “Our Europe. Our Rights. Our Future” report.

It was clear from the report that young people want to be heard and considered, with numbers reaching 70 percent in the EU, but the reality is much different. “Some adults think that their opinion is the one that is correct, and they don’t listen nor respect what we are saying,” noted a young Portuguese surveyed.

“Two-thirds of the children were unhappy with the way cities or towns engage with them, and almost half felt they were never listened to by decision-makers in their city,” data showed.

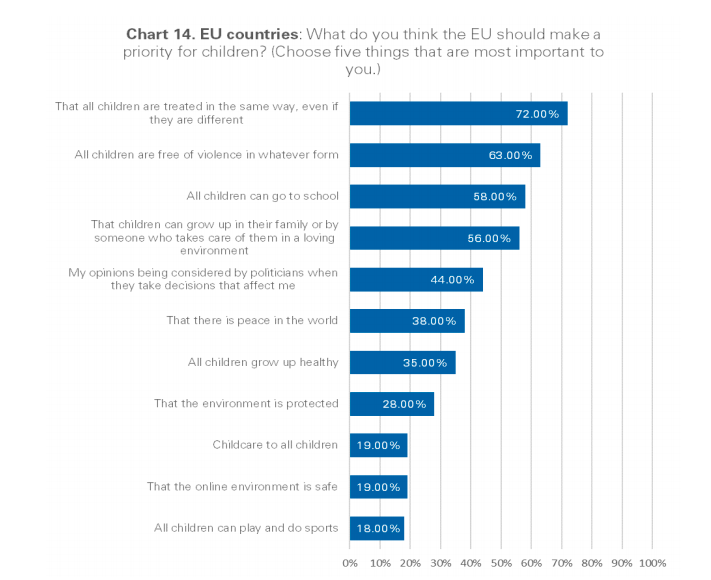

Looking ahead, young people consider equality, education and violence should be the EU’s top priorities for children.

For 72 percent of the participants, all children should be treated equally, regardless of background. The second priority was combating violence against children with 63 percent, followed by ensuring education for all (58 percent) in the third place.

Another priority that took center stage was ensuring children can grow up in their family or with someone who takes care of them in a loving environment with 56 percent.

Some children went further to call the EU to action by criticizing its handling of migration and asking for active participation in solving the problems they face in their home countries.

An unaccompanied minor from Western Africa said, “all the responsibilities are based on the European Union. If we leave everything to come here, it’s because there’s a reason. Instead of fighting against immigration, they should fight against the war, against what forces people to flee.”