03:21

Germany reported its first coronavirus case in late January last year, and on March 8, a person died of COVID-19, the first one to die of the disease in the country. Since then, hardly anything has remained the same.

On March 18, Chancellor Angela Merkel addressed the nation on TV, saying the country faced the most serious challenge since World War II and that it requires the country to "act in solidarity and unity."

A few days later, the country entered lockdown for the first time. Restaurants, cinemas as well as schools and kindergartens were all asked to close. Businesses like airlines ground to a halt.

People stopped hugging and shaking hands. Many experienced working from home for the first time. Some learned new skills during the lockdown, while some got depressed. Words such as coronavirus, COVID-19, lockdown, quarantine, ICU and social distancing dominated everyone's everyday life.

Now, it's been a year since Germany's first lockdown. In that time, changes were made to the country's pandemic laws as a result of the crisis, with the government saying amendments were needed to help better manage future disease outbreaks.

While COVID-19 infection rates in Germany did fall due to the lockdown measures in March, as the autumn came along, a second coronavirus wave flared up. To worsen the situation, people had relaxed their guard during the long summer: they basked in the sunshine and gave up face masks, believing the worst was over, while all those behavior made the situation even worse.

By October, daily new infections rose to 4,000, and Merkel warned that action must be taken. In November, a second lockdown was imposed in the country. Although Germany's vaccination program had begun by the end of 2020, it did not start smoothly due to production and logistics problems.

As of today, Germany has reported 2,502,122 coronavirus cases and 72,470 deaths. The country on Thursday once again announced plans to extend the coronavirus shutdown by three weeks until March 28, but with some restrictions lifted, particularly in areas with a low incidence of coronavirus cases.

Yet, after one year of struggling from the coronavirus and the lockdown measures, a growing chorus of voices is calling for the country to look back and review its response to the pandemic.

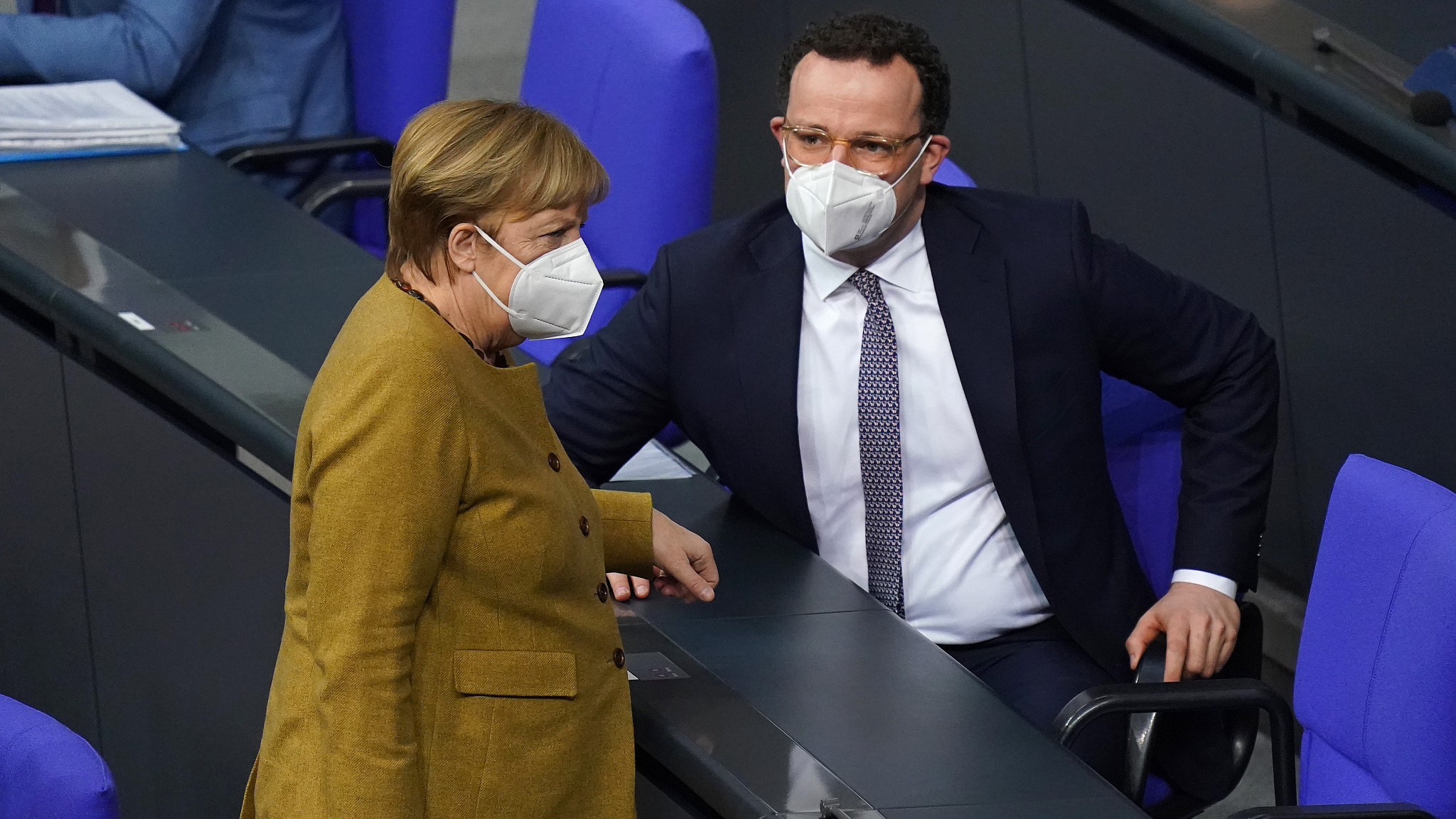

German Chancellor Angela Merkel speaks with Health Minister Jens Spahn prior to debates at the Bundestag, Berlin, Germany, March 4, 2021. /CFP

German Chancellor Angela Merkel speaks with Health Minister Jens Spahn prior to debates at the Bundestag, Berlin, Germany, March 4, 2021. /CFP

Public concern over long-term impact of pandemic laws

The crisis has been a major test for Germany's emergency response regulations, with various aspects of managing the crisis simply coming down to regular negotiations between Chancellor Merkel and her 16 state premiers.

"They passed a so-called pandemic law, a new pandemic law. We had one before but this one is tailored for something like the COVID-19 pandemic. It essentially allows the Federal Government, with a forward interval, to constantly continue with lockdown policies. They have to be determined by a majority in the parliament, in the first chamber of the Bundestag, but with this current government with such a large majority, the two biggest parties working together, it's essentially possible, as we have seen, to extend and extend and extend," Christian Schweiger, a visiting professor in the Institute for Political Science at Chemnitz University of Technology said.

Given Germany's decentralized system of government, state premiers still get the final say on whether decisions made in Berlin are enforced at a local level. It means that throughout much of this pandemic, leaders from all sides of politics have sought to present a united front.

But while regional leaders and the Chancellor have in many ways been in lockstep throughout much of this pandemic, cracks are starting to emerge as difficult decisions have to be made about ending lockdown. Some states are itching to open up earlier, while others are opting for more caution.

There are also some concerns over the pandemic laws' long-term impact, including whether things like travel bans and vaccine passports could undermine individual freedoms.

"People see that as very critical. Basically taking away freedoms that are constitutionally guaranteed in Germany without discussing why and how and for how long. In Germany, there is always the superior referee above everything is the Federal Constitutional Court. It hasn't made any major ruling on this but I expect there will be something coming. People will ask the Federal Court to rule," Schweiger said.

While Germany is just starting to see some light at the end of the tunnel in its ongoing fight against COVID-19, the lasting legal impact of this crisis could likely be felt for many years to come.