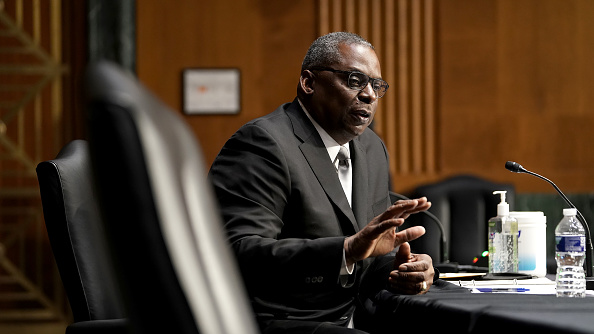

President Joe Biden's nominee for Secretary of Defense, retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin, answers questions during his confirmation before the Senate Armed Services Committee on Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C., U.S., January 19, 2021. /Getty

President Joe Biden's nominee for Secretary of Defense, retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin, answers questions during his confirmation before the Senate Armed Services Committee on Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C., U.S., January 19, 2021. /Getty

Editor's note: Freddie Reidy is a freelance writer based in London. He studied history and history of art at the University of Kent, Canterbury, specializing in Russian history and international politics. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

U.S. Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin is due to arrive in India next week, according to Reuters reports. The visit comes at the end of a tour alongside U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, which also includes Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK).

Austin's arrival will be the first major defence mission of the Joe Biden era and comes at a strategically important time for India as the nation seeks to define its role within the region.

The decision of the Biden administration to reaffirm defence ties with its traditional regional allies, the ROK and Japan, is, perhaps not an unsurprising move. What is significant is the extent to which the U.S. sees its own interests as being intrinsically linked to the region's security.

The Pentagon was keen to underscore that the U.S. would reaffirm "the United States' ironclad commitment to the security of the Republic of Korea", and by extension, U.S. interests at its closest military outpost to China.

India, however, does not yet share the same level of military cooperation as Japan or the ROK. However, as friction between India and China has intensified in recent years, New Delhi has arguably spotted an opportunity to trade strategic regional cooperation for military assistance.

A statement from India's Defence Ministry stated that "both sides are expected to discuss ways to further strengthen bilateral defence cooperation and exchange views on regional security challenges and common interests in maintaining a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific region."

The timing of the statement is unfortunate and could strain the ongoing bilateral dialogue between India and China in the wake of skirmishes in Ladakh.

In a separate development, India's telecoms department is set to ban Huawei and ZTE by introducing a "blacklist" procurement system in June, effectively blocking the two firms amid security concerns. These concerns have been rebuffed, and both companies have offered to enter "no backdoor" deals to address concerns.

These moves are in addition to Prime Minister Narendra Modi's decision to block Chinese entities from purchasing Indian shares, as the nation embarks on a Thatcherite policy of privatisation set to raise $23 billion this year.

It is hard to view the cumulative sum of these actions as anything other than a rebuff to Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi's call for constructive engagements: "It is important that the two sides manage disputes properly and at the same time expand and enhance cooperation to create enabling conditions for the settlement of the issue."

Then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (2nd L) and U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper (1st L) meet Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi, India, October 27, 2020. /Getty

Then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (2nd L) and U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper (1st L) meet Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi, India, October 27, 2020. /Getty

The continued significance of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad including the U.S., India, Japan and Australia also increases tension, but as one former Indian security agency pointed out in an interview in ThePrint, "India can never be an ally of the U.S., (but) we can be good partners."

Indeed, while Austin's visit is significant, India's relations with the U.S. are arguably more closely related to India's own strategy, rather than a genuine defence alignment with the U.S.

By the Defence Ministry's own admission, India wants to focus on "defence trade and industry cooperation" – in other words, "American know-how" and access to U.S. hardware.

India is embarking on a massive program of military upgrades, replacing much of its obsolete Soviet-era equipment. A major stumbling block in India's aspirations though is the commitment to the Russian S400 air defence system, Turkish use of which has caused a major row within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Turkish exclusion from the F35 fighter program – a likely defence aspiration of India's.

There will therefore need to be a large degree of compromise to secure U.S. concessions. Washington is keen for Indian cooperation as U.S. troops are due to begin withdrawals from Afghanistan, so there is perhaps room for manoeuvre.

What is certain though is that while India is happy to have the additional leverage of U.S. support, it will strongly resist policy alignment – Modi's government is set on asserting India's own regional claima.

In a continuation of the Donald Trump era, President Biden is seeking strategic containment of China in the Indo-Pacific. When it comes to India though, the U.S. could instead find itself unwittingly the facilitator of Indian foreign policy.

The U.S. must, therefore, ensure that any military initiatives are confined to reasonable defensive postures, avoiding the risk of a regional arms race, and instead encouraging an environment that best facilitates a peaceful dialogue.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)