The oldest man elected president in U.S. history is turning to cutting techniques on social media to sell his policies to the American public.

Having first hired PR agencies to push messages to younger voters during his election campaign in 2020, Joe Biden is now embracing a direct-to-voter digital plan to talk to Americans that traditional social media techniques – let alone traditional media strategies – cannot reach.

Influencer army

Influencers are known for selling makeup and gadgets online, but increasingly they're also a political force, hired in their millions in the United States to push political messages or support candidates and attempt to sway public opinion or algorithms.

The influencer industry has steadily become a staple of online life, but in a trend accelerated by a COVID-19 pandemic that has curtailed the face-to-face retail politics that Biden grew up with, agencies representing people on TikTok, YouTube, Instagram and others are part of a rapidly growing industry.

U.S. President Joe Biden is shown delivering a primetime address on an iPhone near Times Square in New York City, March 11, 2021. /Getty

U.S. President Joe Biden is shown delivering a primetime address on an iPhone near Times Square in New York City, March 11, 2021. /Getty

Companies like Main Street One do a lot of the heavy lifting on the progressive side of U.S. politics. It has a network of over six million micro-influencers, which it is paid to deploy for political and commercial campaigns.

“People are most influenced by members of their community, who share their affinities and beliefs,” Main Street One’s mission statement reads. “And, we put them together to win narratives online for campaigns, causes, and companies.”

Unlike big-name surrogates who appear on TV or online to represent a government or candidate, the members of these micro-influencer armies are rarely famous beyond their own communities – they may have only a few thousand followers – but crucially, they are trusted by those who watch or read them.

“There is a massive erosion of trust among consumers today,” Curtis Hougland, founder of Main Street One, told the AdAge podcast. “They don’t trust government. They don’t trust the media in the same way. They don’t trust advertising and brands in the same way.

“So ultimately, as a brand, you’re somewhat limited in what you can say as well. So you need to find third parties. You need to find advocates, you need to find supporters – whether those are employees, former employees, content creators, social influencers.”

Nano- and micro-influencers hold down ordinary jobs. They speak in language that reflects everyday life. They’re the person a candidate might reference in a speech to make a point more relatable – Joan, a farmer from Arkansas, Javier, a businessman from California – or the host of a small but influential podcast that speaks to a specific, engaged audience.

The Biden strategy

The Biden digital approach is somewhat different from that of younger members of his party.

While Democratic representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has led the way in digital outreach, putting herself front and center by playing viral games on Twitch with 400,000 watching on, the Biden communications team is taking a more low key but broader approach post-election.

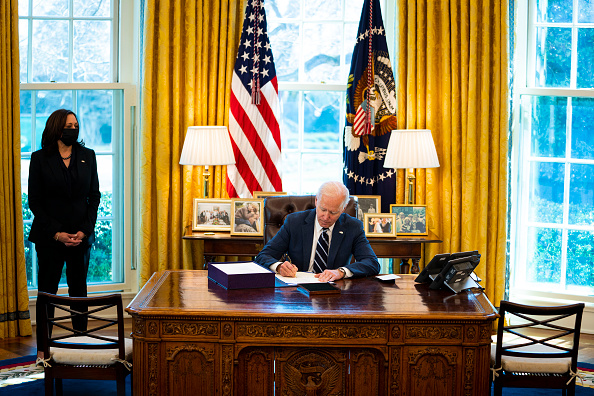

President Joe Biden signs the $1.9-trillion COVID-19 relief bill into law as Vice President Kamala Harris looks on in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, D.C., March 11, 2021. /Getty

President Joe Biden signs the $1.9-trillion COVID-19 relief bill into law as Vice President Kamala Harris looks on in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, D.C., March 11, 2021. /Getty

Biden himself appeared in interviews with bloggers during his campaign, but the approach from the White House involves both aiding online personalities with a niche audience by providing interviewees and, as Democratic groups did during the 2020 election campaign, recruiting micro-influencers to push talking points and put them in a relatable context.

“The idea is to find influencers who've earned the trust of dedicated audiences," Axios reported in mid-March. “They come with a set of unique followers on platforms like Instagram that the White House would be unable to reach through its own social media following.”

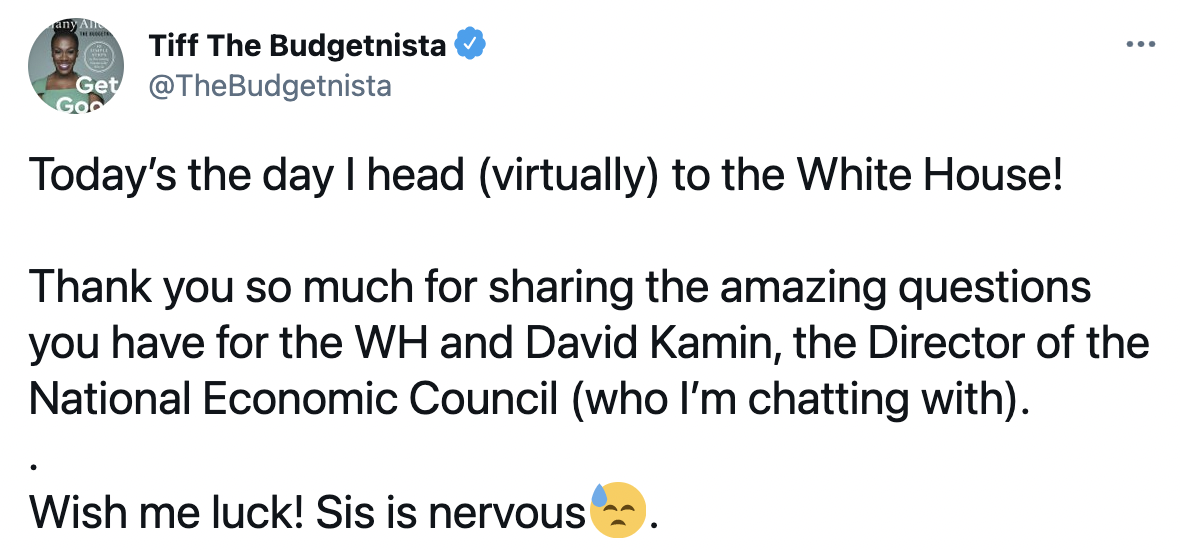

One prong of the strategy was rolled out during the bid to sell Biden's $1.9-trillion stimulus package, that was signed into law on March 11. On March 3, Tiffany Aliche, otherwise known as The Budgetnista, interviewed National Economic Council Director David Kamin in the run up to the passing of the bill.

White House officials lined up to give bloggers interviews about the stimulus package and allowed them to use the content as they wished. Aliche, who has become a trusted figure online as a “personal financial educator” subsequently posted her interview across social media.

Tiffany Aliche, a personal finance blogger, tweets before interviewing the director of the National Economic Council. /@TheBudgetnista

Tiffany Aliche, a personal finance blogger, tweets before interviewing the director of the National Economic Council. /@TheBudgetnista

Historically, the target audience of the online campaigns has often been a younger demographic which skews to the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

But with older Americans increasingly active online – and always important constituencies given their tendency to vote – they are just as likely to be targets, along with those who don’t pay attention to mainstream political programming or news.

The micro-influencer trend is particularly geared towards older or disengaged groups. Main Street One has jumped on that trend, putting together a half-million-strong influencer group of seniors. And targeting similar groups via Facebook was hugely successful for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

Blurred lines

Big players use bespoke programs to recruit influencers by searching for existing online users who fit a required criteria, briefing them on what a specific campaign requires and paying them for delivery.

But there are many routes to deploying influencers in support of a candidate or cause.

In 2019, Buzzfeed revealed that fashion blogger Amanda Johnson was matched to a campaign posted on influencer platform AspireIQ to post support for 2020 presidential hopeful Cory Booker. Individuals or entities pitch a campaign on the platform, and interested influencers can offer their services for a fee.

The Booker-supporting Super PAC which pitched the campaign defended the tactic, despite the Buzzfeed story generating a minor controversy over the ethics of such a partnership.

"This is simply another way to engage dedicated grassroots supporters online, and those supporters will be compensated for their time in the same way that more traditional campaign efforts like canvassing are also often compensated,” a spokesman for the Super PAC told Buzzfeed.

In theory, influencers who are paid to take part in any campaign – for lipstick or for a presidential candidate – should disclose it in the promotional content. But it’s difficult to police and far from all influencers clearly label their content, which in turn means followers don’t necessarily know the person is being paid to promote the given cause.

2020 presidential candidate Cory Booker takes a selfie with an attendee during a campaign stop in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., August 7, 2019. /Getty

2020 presidential candidate Cory Booker takes a selfie with an attendee during a campaign stop in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., August 7, 2019. /Getty

The use of paid influencers has highlighted several areas in which online campaigning has added additional gray lines to the already blurred rules governing electioneering in the U.S.

For example, TikTok, Facebook (which owns Instagram) and Twitter banned paid political advertising around the November 3 election.

Yet, while TikTok’s ban included influencer content paid for by campaigns – and it removed anti-Trump videos which were created by paid-for influencers during the campaign – Facebook and Twitter’s did not.

The use of multiple micro-influencers can also sway the trends and recommendations on social media platforms.

“The use of broadscale coordination of influencers, particularly small-scale nano-influencers who are basically 'regular' users, in efforts to dictate outcomes on digital systems amounts to computational propaganda by other means," a 2020 study by the University of Texas warned. “Here, political groups may not be using bots or sockpuppets, but they are seeking similar outcomes.”

But as regulatory agencies grapple with how to govern new trends in the online space, the use of influencers for political purposes is only becoming more widespread and sophisticated.

Biden will hold the first formal press conference of his presidency on Thursday, a two-month delay that has led to criticisms from some on the right and in the media.

In the wake of two mass shootings, controversy over immigration policy and a mooted multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure plan, there’ll be plenty to talk about on both sides of the political divide – those conversations are increasingly online, and shaped by influencers.