A woman beats a pan during a protest in favor of Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro's impeachment in front of the headquarters of Planalto Palace amidst the coronavirus pandemic in Brasilia. / Getty

A woman beats a pan during a protest in favor of Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro's impeachment in front of the headquarters of Planalto Palace amidst the coronavirus pandemic in Brasilia. / Getty

Over one year after the detection of COVID-19 in Brazil, the virus continues to ravage the South American country and doesn't show signs of abating. On the contrary, it seems to be worsening. On Tuesday alone, 3,158 people died from the coronavirus, the highest daily total since the pandemic was detected inside its borders in February 2020.

Data from a coalition of Brazilian newsgroups tracking the pandemic since Bolsonaro's government was accused of trying to suppress such information last year, showed 84,996 new infections on the same day. Brazil has the second-highest death toll in the world, 298,843, with over 12 million infections. Only 2.6 percent of Brazilian adults have so far received two vaccine doses, according to a Fiocruz survey, while 7.6 percent of the population, or 12.1 million people, have received one shot.

With the number of cases and deaths increasing and reports of lack of ICU beds, medication, and not enough efforts to acquire and vaccinate its people, President Jair Bolsonaro addressed the country in a four-minute speech for radio and tv.

"We are doing and will make 2021 the year of vaccination for Brazilians. We are tireless in our fight against coronavirus," he said.

Promising to vaccinate the whole population by the end of the year, reaching 500 million doses, Bolsonaro assured, "very soon, we will resume our normal lives."

He defended the government's pandemic response, saying it never stopped taking "important measures to fight the virus and the economic chaos that could create unemployment and hunger."

Senior citizens await to receive the coronavirus vaccination shot at a vaccination post in the Santa Cecilia Basic Health Unit on March 15, 2021 in Sao Paulo, Brazil. /Getty

Senior citizens await to receive the coronavirus vaccination shot at a vaccination post in the Santa Cecilia Basic Health Unit on March 15, 2021 in Sao Paulo, Brazil. /Getty

'Panelaço' protests

But the speech didn't sit well with the public. Citizens across the country, including Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazilia, Salvador, Belém, Curitiba, and Belo Horizonte took their pots and pans out in protests that echoed through the night, according to Reuters, a gesture that was seen in the early phase of the pandemic. "Murderer!" and "Liar!" were some of the cries heard from the balconies in the "panelaço" (casserole) protests, according to local media.

His words didn't match previous actions, since he has publicly downplayed the virus as a "little flu," sowed doubts over the vaccines, fought state and local lockdown measures, led substantial gatherings, dismissed mask mandates, and advocated unproven remedies such as hydroxychloroquine.

This formal television address, for example, happened after three failed attempts in March when he was convinced to cancel because he intended to criticize movement restrictions adopted by governors and mayors in an effort to control the virus spread, Folha reported.

A recent poll by Datafolha found that Bolsonaro's administration was rated as bad or terrible by 40 percent of respondents, compared with 32 percent in an early-December survey. Just under a third of respondents rated his government as good or excellent, versus 37 percent in the previous poll. Still, a majority of Brazilians are now against his impeachment.

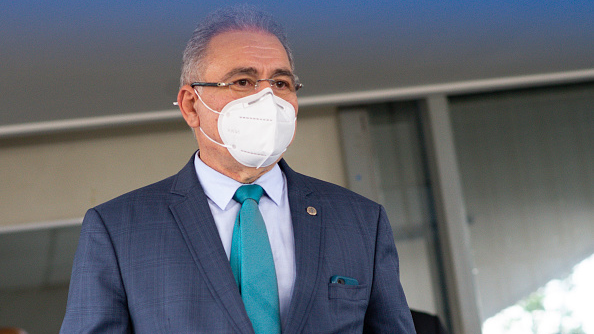

Marcelo Queiroga, Brazil's new health minister, arrives for a press conference at the Ministry of Health in Brasilia, Brazil, on Tuesday, March 16, 2021. /Getty

Marcelo Queiroga, Brazil's new health minister, arrives for a press conference at the Ministry of Health in Brasilia, Brazil, on Tuesday, March 16, 2021. /Getty

Fourth health minister and more political drama

Also on Tuesday, Bolsonaro swore in cardiologist Marcelo Queiroga, the fourth health minister since the pandemic began, in a closed ceremony. The doctor replaces Eduardo Pazuello, an active-duty army general who has overseen most of the pandemic response.

Queiroga said he was called to continue his predecessor's work and the president's policies, which is expected but still not very encouraging. Pazuello's two predecessors both left the government after clashing with Bolsonaro's views on COVID-19.

Amid this health emergency, Brazil continues to struggle with a political crisis.

The country's Supreme Court ruled his fierce political rival, former leftist President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, had not been treated impartially in graft probes that led to his convictions. The decision appears certain to ensure the far-right former army captain will face Lula in next year's presidential vote in which they are both expected to run.

A dramatic reversal by Justice Carmen Lucia led a five-judge panel to find former judge Sergio Moro had made biased decisions in overseeing the graft probe known as Operation Car Wash, throwing out evidence that could have been used against Lula.

(With inputs from Reuters.)