Last week, Stellantis, Nissan and Chinese electric vehicle maker Nio joined an array of other car manufacturers in announcing new production cuts as the global supply of semiconductor chips is running short.

A by-product of the COVID-19 pandemic, looming behind the announcements is a global supply chain crisis that's increasingly taking its tolls on businesses that bank their growth on electronization.

How it all started

As the car market took a hit during the height of the global pandemic, semiconductor orders placed by automakers plummeted. Chip manufacturers thus shifted the focus of their product line to accommodating industries like video game and computer where demand was on the rise due to sweeping stay-at-home orders.

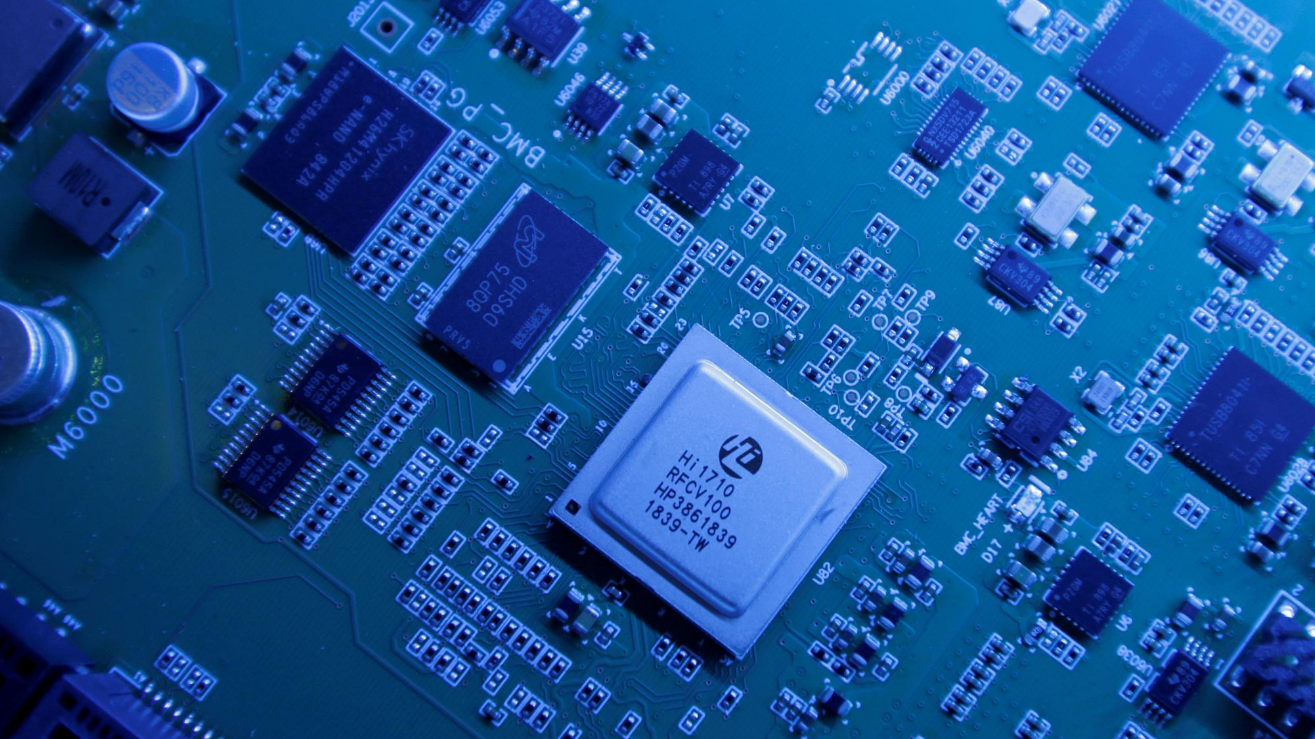

Hi1710 BMC management chip, seen on a Kunpeng 920 chipset designed by Huawei's Hisilicon subsidiary, is on display at Huawei's headquarters in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China, May 29, 2019. /Reuters

Hi1710 BMC management chip, seen on a Kunpeng 920 chipset designed by Huawei's Hisilicon subsidiary, is on display at Huawei's headquarters in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China, May 29, 2019. /Reuters

But as pandemic-induced lockdowns ease worldwide and demand for vehicles has bounced back, car manufacturers are rushing to the now-preoccupied chip foundries for supply, but to no avail.

Given that the entire semiconductor business is built-to-order and that there is an incredibly long lead time due to the complexity of making chips, car makers are either finding themselves put to the back of the line or not expecting the delivery of their semiconductor orders anytime soon.

The shortage has sent shock waves throughout the entire supply chain – car makers run out of chips; chip makers run out of equipment; equipment makers ran out of raw materials, Wang Xiaolong, research director at ICwise, a Shanghai-based market research company in semiconductor and electronics industry, told CGTN.

For vehicles, semiconductor chips are indispensable parts that power up systems ranging from in-car entertainment to driver assistance. The number of semiconductors needed in one vehicle could be as many as hundreds.

But automotive chips, compared with chips for consumer products, are harder to come about through research and development, Wang noted. They must be able to withstand heat, be able to endure under much greater forces and must be highly reliable under all circumstances.

RAM memory chips are seen in this illustration photo, June 21, 2017. /Reuters

RAM memory chips are seen in this illustration photo, June 21, 2017. /Reuters

The failure to secure chips has sent car manufacturers scrambling to deliver their products. With plants temporarily shut down and production halted, the companies are expected to endure considerable losses this year.

Ford, which recently halted production at two car plants, said it may lose up to $2.5 billion in its 2021 profit, while General Motors said the chip shortage could cost it $2 billion in earnings.

But automakers are not the only ones hit by the chip shortage. Anticipating that the chip supply will keep running short for some time, companies from other sectors have embarked on panic buying, driving up stock prices in the semiconductor industry and increasingly pinching chip capacity.

What was initially a crisis exclusive to the vehicle industry has evolved to one that affects all businesses needing chips in production.

China's path to seeking self-sufficiency in chips

The global chip shortage has pushed carmakers in China to come to see the importance of semiconductor independence. From traditional carmaker Geely to new energy vehicle giant Nio, Chinese automakers are now rushing to design their own chips, but few have achieved the ability of commercial production.

Newly manufactured cars are seen at a port in Dalian, Liaoning Province, China, April 10, 2020. /Reuters

Newly manufactured cars are seen at a port in Dalian, Liaoning Province, China, April 10, 2020. /Reuters

China's resolve to pursue semiconductor independence can stretch back to June 2014, when the State Council announced the establishment of a national investment fund dedicated to the development of semiconductors. Since then, hundreds of policy funds have been established to support the industry, while venture capitalists also turned to investing heavily in semiconductor startups.

According to China Semiconductor Industry Association, China's integrated circuit sales increased by 17 percent in 2020, reaching 884.8 billion yuan ($134.9 billion). But still, the industry is heavily reliant on foreign companies. In 2020, China bought $350 billion worth of foreign integrated circuits, 14.6 percent more than the year before.

A major barrier to achieving semiconductor independence is that China relies on foreign companies for chip-making equipment and design software, Wang noted, so that even if China achieves major progress in chip design, it lacks the equipment to produce them for domestic use.

BYD, one of China's biggest electric vehicle (EV) makers, has long committed to developing its own semiconductors. During the chip shortage, the company said its self-designed chips can not only meet its own demands but also be supplied to others, but analysts have raised doubt about it as the type of chips BYD makes does not necessarily resolve the crying needs.

Nevertheless, the firm has been able to make so-called insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBT), an integral silicon component in EVs' power management system that's at the core of BYD Semiconductor, for all its vehicles, marking a great leap in the traditionally foreign-dependent sector and a stride towards self-sufficiency.

In 2019, BYD had a share of 18 percent of the IGBT produced in China, while the rest was largely produced by foreign suppliers.

A BYD electric car at the Auto China 2016 in Beijing, China, April 25, 2016. /Reuters

A BYD electric car at the Auto China 2016 in Beijing, China, April 25, 2016. /Reuters

Last year, a large number of chip-related companies sprang up across China, incentivized by the strong state support. According to data from Qichacha, the number of chip-related companies in China increased by 22,800 in 2020, an increase of 195 percent from the previous year.

But still, most of the chip-related companies focus on the downstream operations in the supply chain, instead of the upstream, noted Wang, which means foreign companies that have the stranglehold on raw materials and equipment for chip manufacturing still have a major say over China's chip production.

Late last year, the U.S. Commerce Department imposed restrictions on China's Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation from acquiring U.S.-based parts and technologies that are required to produce advanced chips that are 10 nanometers or below. It has also imposed similar restrictions on Chinese smartphone maker Huawei.

"We need to enhance supply chain security from a holistic perspective," Wang noted. "Chips, raw materials, equipment, design tools… every single part of the supply chain is critical to China's pursuit of semiconductor independence."