Families of special-needs students, supporters, and the students themselves protest outside Boston Public Schools' headquarters in Boston's Roxbury, amid uncertainty over a return to in-person schooling, September 10, 2020. /Getty

Families of special-needs students, supporters, and the students themselves protest outside Boston Public Schools' headquarters in Boston's Roxbury, amid uncertainty over a return to in-person schooling, September 10, 2020. /Getty

Anxiety, anger, frustration and loneliness: most of us have experienced one or the other over the past year due to COVID-19. But for autistic people, for whom even small changes to routine can provoke a meltdown, the hurdles have been even greater.

As we celebrate World Autism Awareness Day, one year into the pandemic, how has COVID-19 affected the lives of people on the spectrum, and are things getting better?

A change in routine

Autism comes in many shapes and colors: that is why those who have it are said to be on the autism spectrum or to have autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Advocates regularly emphasize that there is no "one size fits all" approach to ASD, with some people highly independent, living on their own and working, while others may be non-verbal, have learning disabilities or require round-the-clock care.

Common traits however include a difficulty to communicate and interact socially, sensory issues, a need for routine and a tendency to become easily overwhelmed, which can lead to extreme anxiety and even meltdowns.

In the U.S., about 1 in 54 children has been diagnosed with ASD. In the UK, it is estimated that one in 100 people is on the spectrum. In Australia, the average is closer to one in 70.

Early on in the pandemic, autism organizations and parents warned the disruption brought on by COVID-19 – from lockdowns to constantly changing safety rules – would be felt even more by those with ASD.

Schoolchildren with disabilities such as autism are helped by their teachers in a classroom with social distancing during the closure of Italian schools imposed by the COVID19 emergency. /Getty

Schoolchildren with disabilities such as autism are helped by their teachers in a classroom with social distancing during the closure of Italian schools imposed by the COVID19 emergency. /Getty

While staying at home and socially distancing may have presented little change for some, school closures meant access to education and therapy was suddenly restricted. Many autistic people lost crucial support services, such as carers who would usually come to their home to help them with cleaning, shopping, eating or going out, leaving them isolated and putting an extra burden on their families to take care of them.

Important daily routines were turned upside down: group activities were suspended, home schooling was introduced, daily contacts with friends or colleagues ended abruptly, and taking a stroll or going to the park became difficult overnight.

Uncertainty and restrictions that prevented those in care homes from seeing their families, made things worse.

A report by the UK's National Autistic Society (NAS) entitled "Left Stranded," which surveyed over 4,200 families last summer, found that nine in 10 autistic people worried about their mental health during lockdown, with 85 percent saying their anxiety got worse.

Increased anxiety

Even something as apparently simple and innocuous as wearing a face mask proved a hurdle. Jonathan Stacey, a 45-year-old autistic man, described this in the NAS report.

"I cannot cover my face as it triggers me severely, it makes me shake and sweat immediately… I've been stopped a number of times and asked to put on a mask and each time I've had to reiterate I am exempt, every time increasing anxiety further."

"I recently experienced the first instance of someone pointing an IR thermometer at my head. No warning and held like a gun it started a minor panic attack. Far too scary," he added.

As a result, Stacey said he was even more reluctant than before to go out, to avoid finding himself in such situations.

Massachusetts resident Roberta Biscan uses FaceTime to talk with her autistic son Connor, 15, who lives in a group home, April 4, 2020. She hasn't seen him for four months but Connor is not allowed home

due to the coronavirus pandemic and struggles with that. /Getty

Massachusetts resident Roberta Biscan uses FaceTime to talk with her autistic son Connor, 15, who lives in a group home, April 4, 2020. She hasn't seen him for four months but Connor is not allowed home

due to the coronavirus pandemic and struggles with that. /Getty

Parents have also talked of their children struggling to comprehend the changes around them and their feelings about them, and acting out or just shutting down as a result, taking an emotional toll on their families as well.

"I feel completely alone and unsupported with a child who is regressing further into his own bubble on a daily basis," one parent from Northern Ireland said in the "Left Stranded" report. "I haven't got him outside in 11 weeks and I haven't had a break in as long. He has not been able to do any schooling as home is home and school is school, causing massive meltdowns and trauma."

Long-term effects

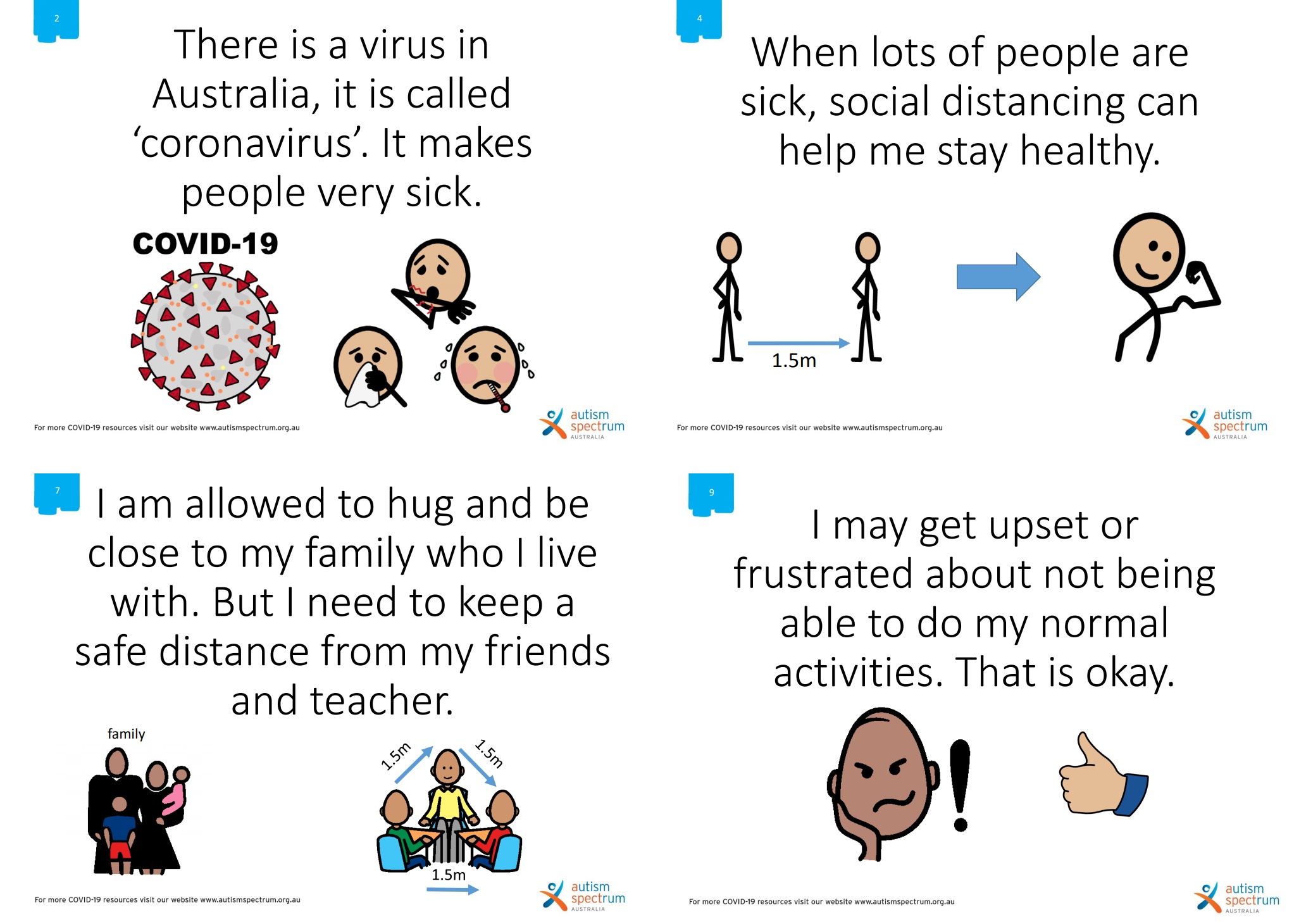

Quickly, many organizations and care services set up online tools to help, sharing advice, videos and social stories – colorful cartoons using simple language to explain things like how to wash one's hands properly and how to cope with change.

Therapy sessions and activity groups went virtual. Webinars explained how to create a new routine at home. And authorities allowed exemptions to mask wearing.

Still, a study looking at how children with ASD and their parents coped with COVID-19 in Portugal found that a majority developed behavioral changes during the pandemic, while neurotypical children did not, and that this was often caused by anxiety, irritability and hostility.

Parents of autistic children also reported higher levels of anxiety in themselves and their children than other parents, illustrating the impact on families.

Excerpts from a social story about social distancing created by Autism Spectrum Australia (Aspect). /Aspect

Excerpts from a social story about social distancing created by Autism Spectrum Australia (Aspect). /Aspect

"Our results show a potential important psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic not only in children with neurodevelopmental disorders but in their caregivers as well," the authors of the study, which was published in the Spanish Neurology Society's journal Neurologia, noted.

"Physicians must be prepared for the post-pandemic surveillance of mental disorders among families," they warned.

Stacey, the UK man cited in the "Left Stranded" report, agreed autistic people would suffer setbacks: "All those years of learning social norms has been pushed to one side by this pandemic."

Medical implications

On top of the social and emotional impact, autistic people have been among those most at risk medically from COVID-19.

Autism often overlaps with other underlying medical conditions, and those living in care homes were disproportionately hit by the disease early on.

In a letter in December calling for people with learning disabilities and ASD to be given priority in getting the vaccine, autism organizations in the U.S. noted that "individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities are at a greater risk for severe complications and death from COVID-19, especially if they have underlying health conditions or are living in congregate settings."

Public Health England found that the death rate among people with learning disabilities during the first wave of the pandemic was six times higher than among the general population. Among young people aged 18 to 34, the difference was 30-fold.

There was also evidence that autistic people were not afforded the same kind of medical care as neurotypical patients with COVID-19, with advocacy groups in the U.S. pointing to policies that favored saving able patients over disabled ones.

The staff of PizzAut, a pizzeria run by autistic guys, prepares and delivers pizzas for health professionals at the San Gerardo hospital in Monza, Italy, January 15, 2021. /Getty

The staff of PizzAut, a pizzeria run by autistic guys, prepares and delivers pizzas for health professionals at the San Gerardo hospital in Monza, Italy, January 15, 2021. /Getty

Reports even emerged earlier this year in the UK that "do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR)" notices had been put in the files of people with learning disabilities, including people with ASD, without their knowledge, meaning they would not be revived if they fell ill with COVID-19.

Throughout the pandemic, autistic people have often been ignored although they are among the most vulnerable to the disease, organizations and charities say. Now the call is for autistic people and their caregivers, especially those with high support needs, to be given priority on the vaccine.

Back to normal or more change?

For people who dislike change, the last 12 months have been a struggle: not just the initial lockdowns, home schooling and social distancing, but also the constant policy adjustments that have caused confusion even for those without autism.

As countries take a day, week or month to raise awareness about autism, the focus is now on preparing for the next set of changes.

"The easing of the lockdown rules and return to school has been welcome for many but means more change and some autistic people are anxious about this," NAS head of policy and public affairs Tim Nicholls said in a statement sent to CGTN.

Many problems were exacerbated by the pandemic but already existed before, so from funding to policies, "many things need to change if we're to create a society that works for autistic people," he noted.

"But everyone has a role to play too, by finding out more about what it's like to be autistic and the small things each of us can do to make the world a little more autism friendly… this would improve hundreds of thousands of lives.”