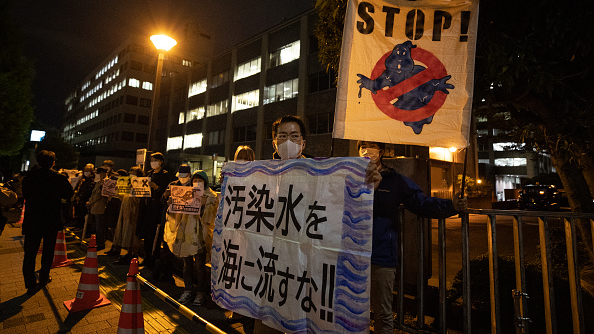

People demonstrate outside the prime minister's official residence in Tokyo, Japan, April 13, 2021. /Getty

People demonstrate outside the prime minister's official residence in Tokyo, Japan, April 13, 2021. /Getty

Editor's note: Freddie Reidy is a freelance writer based in London. He studied history and history of art at the University of Kent, Canterbury, specializing in Russian history and international politics. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

In Tokyo, global alarm has been triggered by the Japanese government's announcement of the planned release of over 1 million tonnes of treated radioactive water into the sea.

The radioactive water is being stored as part of the clean-up operation in the aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. The continued consequences of the disaster are a harsh reminder of the potential danger of nuclear energy and the necessity for strict controls to manage both global nuclear security and to protect against human, ecological and environmental impacts.

Despite some dissenters in the Japanese cabinet, Yoshihide Suga's government has concluded that the release of the water is the best course of action and "most realistic." The Tokyo Electric Power Company (TepCo), which operates the site, is now on course for the first release in two years' time as part of a 10-year program.

The news comes as a major blow to the already decimated coastal fishing industries of Fukushima Prefecture. One of the major challenges facing TepCo is the latent tritium in the water which cannot be removed in the same way other isotopes can. It has been deemed though that small quantities of the water still contaminated with tritium can be safely released.

Despite being seen by many governments as a vital tool in meeting the objectives of carbon neutrality, nuclear energy carries with it the inherent problem of how to safely deal with nuclear waste in times of safe operation as well as after major incidents.

The effective storage of waste is integral to global nuclear safety. Examples of inadequate storage methods abound, in one case in Germany, a Soviet-era waste dump in Saxony will require decades of work to prevent a potentially lethal incident. Svenja Schulze, Germany's environment mister, explains, "Three generations operated nuclear power in Germany, and now 30 generations or even more will have to suffer the consequences."

Indeed, the feeling of injustice at one generation dealing with the consequences of the previous generation is akin to the frustrations and concern of Japan's neighbors.

China and South Korea have both expressed dismay at Tokyo decision. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian urged Japan to "act in a responsible manner." YTN reports that South Korea has gone a step further by summoning the Japanese ambassador as well as stating its intention to step up nuclear monitoring in the area.

Tanks containing radioactive wastewater are seen from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, September 18, 2013. /Getty

Tanks containing radioactive wastewater are seen from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, September 18, 2013. /Getty

In contrast to the concerns of the region, the U.S. appeared to endorse the decision to release the radioactive water and continue with the decommissioning of the facility.

The U.S. State Department released a statement stating that "Japan has weighed the options and effects, has been transparent about its decision, and appears to have adopted an approach in accordance with globally accepted nuclear safety standards."

While International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi did declare that "releasing into the ocean is done elsewhere. It's not something new. There is no scandal here," the concern both within the region and in neighboring countries is in monitoring the disposal and potential effects at a pace which is containable.

In addition to the duty felt in protecting the safety of citizens is the duty to protect their livelihoods.

While the undeniable challenge of removing tritium is known, TepCo also stands to benefit from alleviating itself of the 100 billion yen a year cost of storing the radioactive water, a fact which has called into question the driving motivations of this method of disposal, if not its pace.

In Japan, the chairman of the National Federation of Fisheries Hiroshi Kishi reiterated his concern to the prime minister in bilateral talks as Greenpeace Japan damned the government for "once again failing the people of Fukushima."

While tritium is harmless in small doses, it does possess a 12-year half-life and is ingestible. The reputational risk to the fish market alone in the surrounding waters of Fukushima and beyond will likely bring about significant economic hardship.

Illustrative of the challenge facing the industry and others in the region is the powerful and lingering image in 2011 of former cabinet spokesman Yasuhiro Sonoda's trembling hand as he drank a glass of decontaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Such a level of trepidation represents the challenge the region and others could face in convincing people of the safety of their waters, food and the sustainability of the natural environment.

It is little wonder therefore, that nations and regions have uniformly called for caution, oversight and consensus in the next chapter of the recovery after one of the greatest human disasters of the last century.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)