The crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in the Fukushima Prefecture town of Namie, northeastern Japan, April 9, 2021. /Getty

The crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in the Fukushima Prefecture town of Namie, northeastern Japan, April 9, 2021. /Getty

Editor's note: Wu Changhua is executive director of the Professional Association for China's Environment. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Here comes the much delayed but timed announcement: Japan will dump millions of tons of treated radioactive wastewater into the Pacific in two years. Such a decision had long been speculated but delayed for years due to safety concerns, protests, and also reputational risks to the host country of a few big international sports events, such as the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics.

The global community won't be able to spare much attention to this headline when grappling with the pandemic and recovery remains top priorities.

Another typical "He Says, She Says" situation, but this round bears very significant implications on global environmental governance and impacts on marine life and human health. Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said recently that ocean release was the most "realistic" option and also an "unavoidable" step, backed by a government panel's opinion after seven years of discussion. He also assured the global community that Japanese government would "take every measure to absolutely guarantee the safety of the treated water."

But how can PM Suga make such a bold commitment when scientists are saying that the long-term impact on marine life from low-dose exposure to such large volumes of water is unknown, and the amount of radioactive materials that would remain in the water is also still unknown? By the way, when the Japanese government stresses the safety of the water by calling it "treated" not "radioactive," keep in mind that the 62 radionuclides found in the wastewater can only be reduced to disposal levels, not to zero.

There is much attention given to tritium today, which is radioactive but proves no effective treatment through the popularly known ALPS. But the risks are much larger. Among the 62 radionuclides, cobalt-60 has a decaying half-life of 5.27 years, strontium-90 of 28.79 years, and cesium-137 of 30 years, but carbon-14 has a half-life of more than 5,700 years. This means that they will stay and impact marine life and human health for a long time.

PM Suga's "take every measure" does not speak the truth. As many of us have learned, there are much more effective, though a bit more costly, technology solutions to achieve non-detect levels on all the 62 radionuclides in the coolant water at the wrecked Fukushima nuclear facility. Purolight, a U.S. technology company, piloted its new ion exchange products and innovative application techniques onsite and achieved to reduce all radioactive nuclides to non-detect levels.

When achieving non-detect levels on all 62 radionuclides, local communities, fishermen, farmers, neighboring countries, government bodies and international institutions would have been put in a very different position than today. And the Pacific Ocean, already stressed out ecologically by pollution and nuclear bomb testing contamination over the decades, would have to bear much less negative impacts on marine ecosystems. And yet, as some observers say, costs and also local protectionism had blocked Purolight's further contribution after the pilot stage.

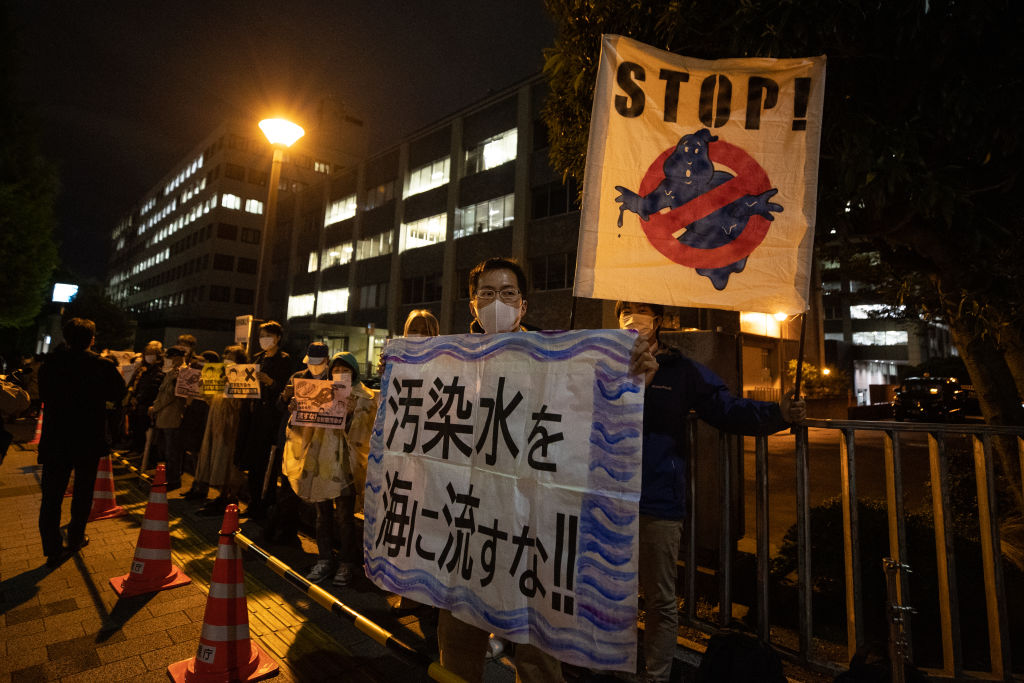

People demonstrate outside of the prime minister's official residence in Tokyo, Japan, April 13, 2021. /Getty

People demonstrate outside of the prime minister's official residence in Tokyo, Japan, April 13, 2021. /Getty

And the prime minister has also assured his people to "address misinformation." But who to trust? Who shall be the final judge of what accounts as misinformation? The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) supports the Japanese government's decision and stated that nuclear plants around the world use a similar process to dispose of wastewater. But, in a recent video message, the IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi also admitted that "the large amount of water of the Fukushima plant makes it a unique and complex case."

This feels like a direct blow to your face and shows how much lagging behind our current governance remains when safeguarding ecological redlines is concerned. More than five years have passed since UN sustainable development goals were endorsed by all nations, and ecological security risk is at the highest level ever, both international institutions and governance are failing to play their due roles.

Critics, including one of the most quoted, Greenpeace nuclear specialist Shaun Burnie, pointed out that East China Sea had already been polluted by cesium leaked from Fukushima since 2011, and the variety of radionuclides that would be discharged into the sea might damage the DNA of humans and other organisms. And a recent scientific study found a tiny bug on the ocean floor of the North Pacific Ocean Rift, 11,000 meters below the surface, with excessive radionuclide dose in its body.

While protests, opposition and confrontation of positions heat up and escalate, we do need to face the real challenge. The designed storage capacity of 1.37 million tons of radioactive wastewater in more than 1,000 tanks, with a used up capacity of 1.25 million tons today, will run out before fall of 2022. Like a time bomb that could explode anytime soon, this matter requires immediate regional, if not global, consultation among related countries and stakeholders.

Today's divergence of positions and geo-politicization of the matter do not help. China and South Korea are strongly against it. The U.S. applauded Japanese "transparency" about its decision. Russia and Canada and some others have not yet voiced their positions. More urgently than ever, the failing global environmental governance shall be revamped up to address such challenges. And this case offers a real-life case to organize such kind of reform and revitalization.

Scientific uncertainty or unknown or confusion proves an obvious barrier for more effective decision-making since the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami that ravaged the facilities. Precautionary principles have been a basic rule of science in uncertainty. As part of the compensation, the Japanese government shall allocate more funding to invest in scientific research, in particular, by deploying cutting-edge technologies, to generate meaningful data, evidence and knowledge foundation to support smart decisions and empower key stakeholders to take actions.

Instead of moving forward with the dumping decision, the Japanese government needs to take some immediate steps to demonstrate its sincerity and sense of responsibility.

We live in a world of constraints today, from climate change, pollution and resource scarcity. We have crossed much of the ecological boundaries, measured by planetary life-support systems, including oceans. Most international standards and practices cannot meet the challenge of the day. In the meantime, addressing science uncertainty remains a daunting task for all of us.

Then we put on the table the real-life case of the Japanese government's decision to dump the treated radioactive wastewater to the Pacific. The picture gains much improved clarity. It becomes a moral and ethics issue. It's about human rights and planetary security. And it shall not be left to one single nation to make such a decision.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)