Asia has been a global economic powerhouse in recent decades. But the region is well on track to a gray future, as Asian countries are growing older faster and on a larger scale than any other parts of the world in history, according to the World Bank.

Countries in East Asia are at the forefront of population aging. Across the board, fertility rates have dropped below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman. A new world low of 0.84 was reported last year in South Korea, while in Japan, the number has hovered around 1.4 since the start of the 1990s.

China is catching up fast. The number of Chinese children born last year plummeted by 15 percent in a fourth straight year of decline, despite lifting the one-child policy. The trend has prompted new calls to "fully liberalize and encourage childbirth" in a working paper published this week by the country's central bank.

From 2020 to 2060, working-age populations will plunge 30 percent in Japan, 26 percent in South Korea and 19 percent in China, according to projections by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development using a broad age range of 15-74.

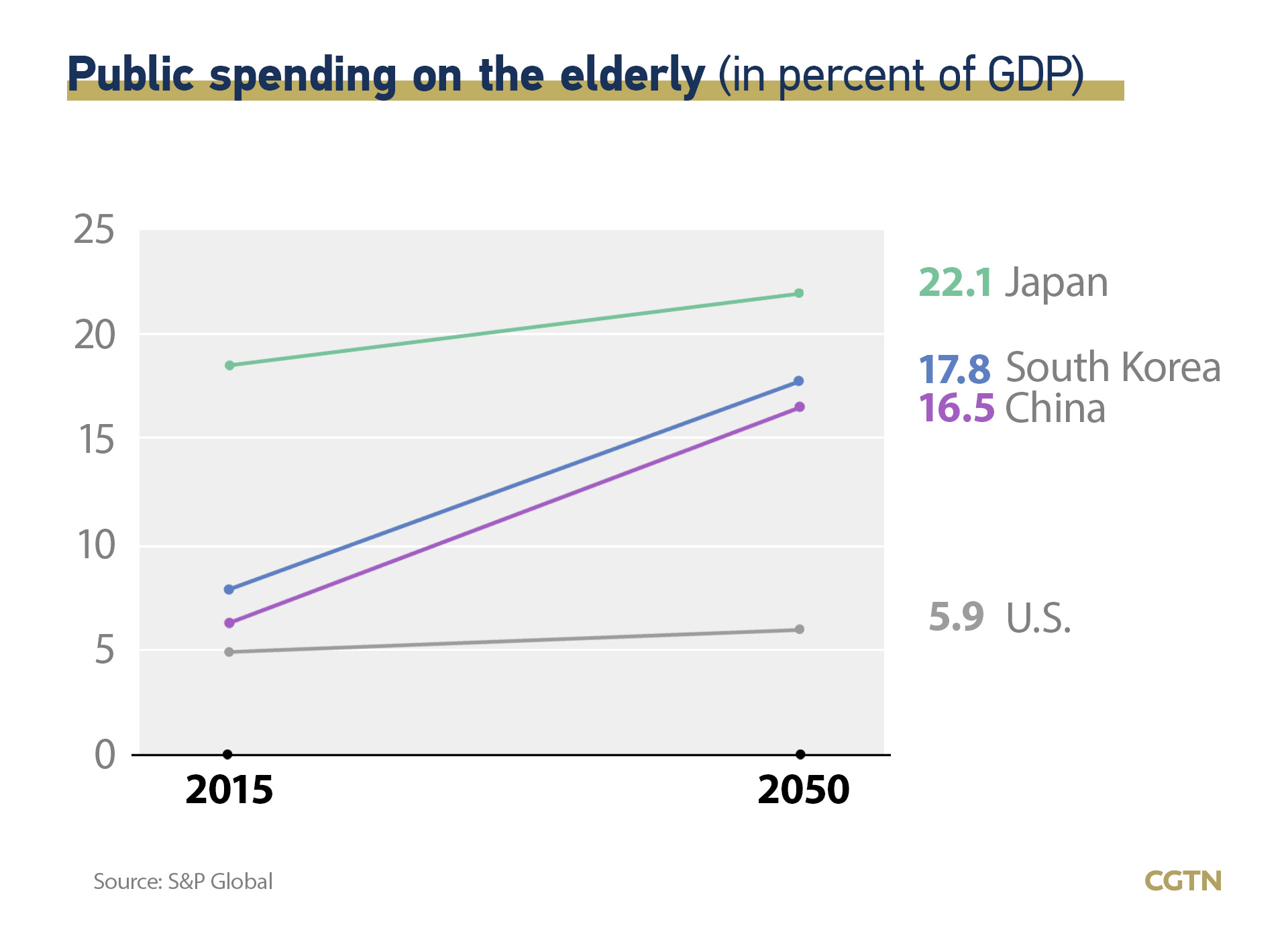

A dwindling workforce and a steep increase in public spending on pensions and long-term care will pose a complex set of challenges for these countries to continue on a path of sustainable development, as shown by a 2015 World Bank report.

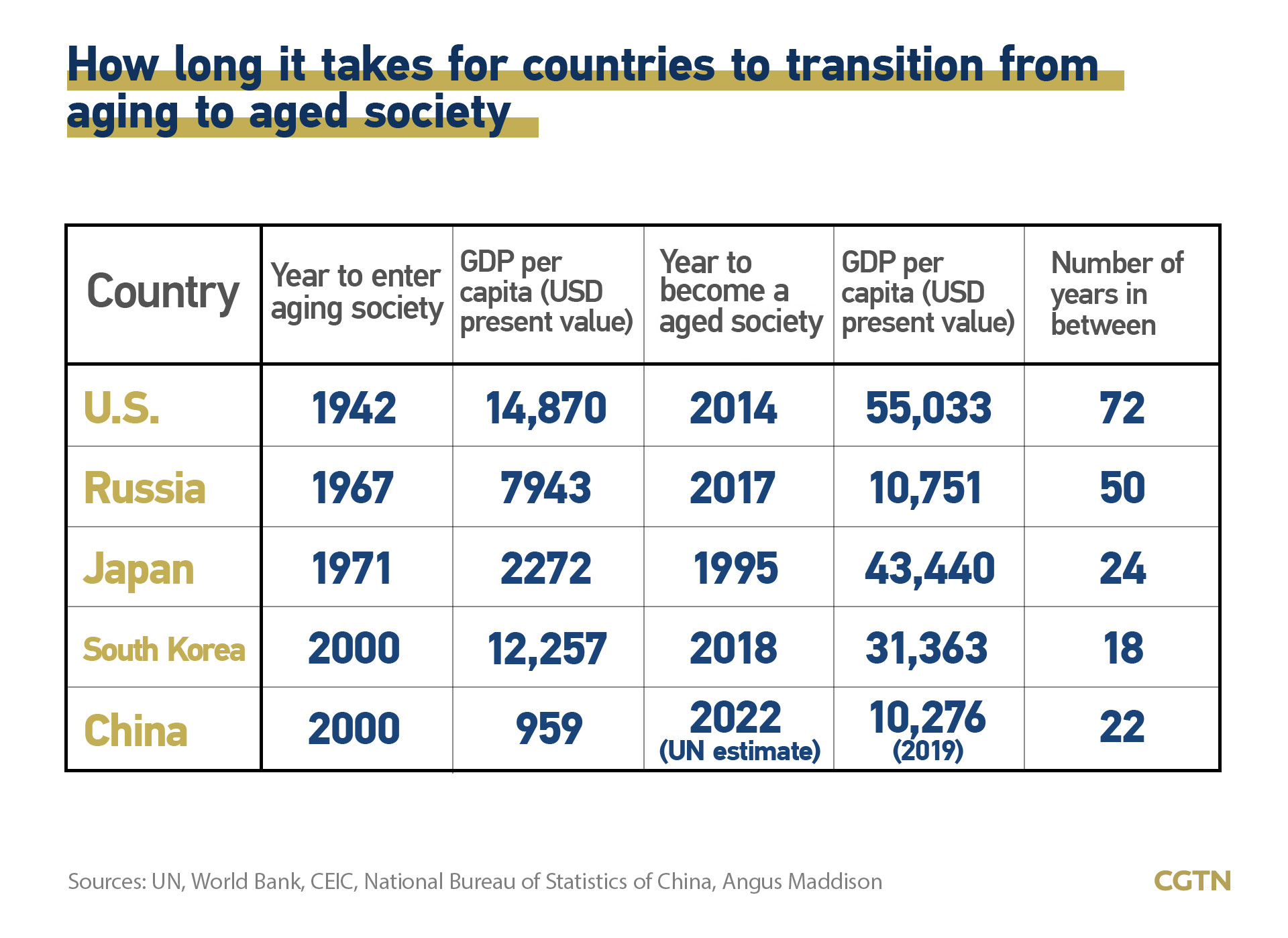

While East Asia is not alone in facing significant demographic changes, the transition from an aging to an aged society for major economies in the region took no more than two decades on average, compared to between 50 years and more than a century in Europe and the U.S.

With the world's largest population, China is expected to become an aged society, with more than 14 percent of the population aged 65 or older in 2022. The country has a more severe aging population problem because developed countries tend to be wealthier in terms of GDP per capita when they reached this milestone, researchers noted in the working paper from the People's Bank of China.

Lessons from Japan

Japan has the oldest population in the world, with over 28 percent of the population aged 65 and older, according to the World Health Organization, making the Asian country a "super-aged" society. The impact of this is evident in the rise in the country's social security spending, which has doubled from 1990.

Japan's working population began to shrink in 1995, coinciding with its "lost decades" of economic stagnation. Although it is not the main reason for the prolonged downturn Japan is stuck in, population aging has nevertheless weighed heavily on its recovery, experts say.

An elderly worker commuting to work in Tokyo, Japan, October 16, 2018. /CFP

An elderly worker commuting to work in Tokyo, Japan, October 16, 2018. /CFP

"Low birthrates and population aging is considered a 'national disaster' in Japan. Now, all policies have to be considered against this backdrop and will be colored by this issue," said Hu Peng, a research fellow at the Institute of Japanese Studies of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Japan started taking the aging problem seriously in 1989, when it was alarmed by a low fertility rate of 1.57. The country has since rolled out a series of generous pro-family policies and built world-class elderly care facilities. But despite its efforts, it has failed to prevent the free fall in births.

With many parallel trends in social and cultural development, Japan's experience serves as a cautionary tale for other countries in Asia. More choices for women, changing attitudes toward marriage, lack of job security among young people and entrenched gender inequalities in the workplace are some of the common factors deterring East Asian young people from starting a family, Hu said.

"Although China and Japan are at different development stages, the challenges for young people in big cities are similar," Hu said. "It requires society to create a more friendly environment for young people."

'Silver economy'

On the other hand, Japan also has one of the highest life expectancy in the world at 84 – a testament to the country's success in maintaining a high-quality social care system.

For decades, Asia's economic success was owed largely to an abundant workforce. But demographic changes are forcing rapidly aging countries to fundamentally rethink population dividend with the new focus on longevity.

In Japan and Singapore, policies designed to help reintegrate retirees back into the workforce have already yielded positive results.

Prolonging a healthy old age and building a society with longevity that allows older people to contribute is the next step for countries like Japan, Hu said.

Asia is also expected to claim the biggest share of the global "silver economy" market by 2030, with the annual spending power of people over 60 reaching $8.6 trillion, greatly surpassing Europe's $5.2 trillion, according to research organization World Data Lab.

Elderly care products from Japanese company Panasonic on display at the China International Import Expo in Shanghai, November 9, 2019 /CFP

Elderly care products from Japanese company Panasonic on display at the China International Import Expo in Shanghai, November 9, 2019 /CFP

But even with a fine-tuned elderly care system, how to sustain it in the long run remains a big question for Japan's policymakers.

"Japan is about 30 years ahead of China with regards to the aging society, and there is not much it has not tried by now," Hu said. "The Chinese society is still full of vitality. If the aging issue is taken seriously and tackled early on, the country might be able to explore a new path different from the one Japan and Western countries are heading down."

(Cover photo and infographics designed by Yu Peng)