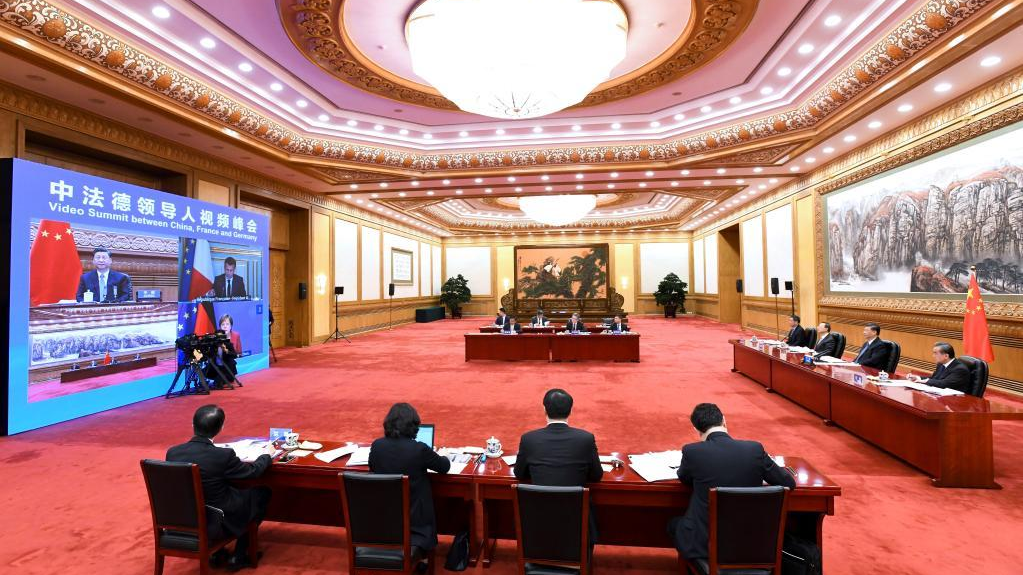

The video summit on climate change attended by Chinese, French and German leaders, in Beijing, China, April 16, 2021. /Xinhua

The video summit on climate change attended by Chinese, French and German leaders, in Beijing, China, April 16, 2021. /Xinhua

Editor's note: Jonathan Arnott is a former member of the European Parliament. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Climate policy in the West has faced a serious problem for years: it has been remarkably insular, based upon a target-driven approach which comes with three major unintended consequences.

First, and most important, it fails to fully grasp straightforward demographics. With China and India alone accounting for over 35 percent of the world's population, there is – to put it bluntly – little chance of any actual impact on global carbon emissions from any approach which is not shared by these countries.

Second, it has – until very recently – failed to consider the basic features of global interconnectivity. Policies designed to lower European emissions have "succeeded," to the extent that they have lowered European emissions, but it is less clear whether they have outsourced pollution to other nations or actually made a meaningful impact on global emissions.

Policies which lead to importing goods from abroad rather than manufacturing them locally are particularly dangerous: they create a feeling that "something is being done," but in practice merely pass pollution on to a third country and increase transport costs. There are, slowly, some signs that this is changing – but the mindset is hard to shift.

During my time in the European Parliament, I recall discussion of so-called "steel dumping" by China. The claim was made that China was exporting steel at below-cost prices, using state subsidies to factories to do so. Consequent anti-dumping measures are taken by Western nations. Yet there was another aspect to the whole debate which was almost completely neglected – the fact that the steel industry is so energy-intensive.

The opening ceremony of the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, New York, U.S., September 23, 2019. /VCG

The opening ceremony of the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, New York, U.S., September 23, 2019. /VCG

The climate legislation designed to cut European CO2 emissions led to an increase in energy prices. Increasing energy prices disproportionately hit the competitiveness of the European steel industry – and, in comparison, steel from India and China appeared more competitive. This certainly contributed to a cut in local emissions, when steel manufacturers in the United Kingdom and elsewhere closed, but if anything it was counterproductive in terms of global emissions.

Third, the West suffers from a form of environmental "tunnel vision." It fixates on global CO2 emissions, while often ignoring other greenhouse gases and other forms of pollution. Attempts to push motorists toward diesel fuel in the early part of this century simply traded one pollutant for another: diesel cars may emit less CO2, but they also produce (among other gases) more NO2.

With recent moves toward electric vehicles, there are signs that this is changing. There are known environmental costs of mining and disposing of lithium, a key component in batteries for electric cars, but these are relatively minor compared with the overall benefits.

April 16's video summit between China, Germany and France was therefore encouraging: it touched on all three of these issues. A target of peak carbon emissions by 2030, and complete carbon neutrality by 2060, will not be a straightforward task for an economy growing at the rate of China's – especially given its status as a major manufacturing and exporting nation. This is nothing new, of course: that target was merely reiterated on Friday.

I'm interested in particular in the focus on China's decision to adopt the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. While CO2 emissions have entered the public consciousness, hydrofluorocarbons have not. They are rarely mentioned in political debate, yet they are powerful greenhouse gases: for example just one molecule of HFC-23 has more warming impact on the atmosphere than 10,000 molecules of CO2. The comparison is not, for specific scientific reasons, a direct one – but it is indicative of the fact that complex problems do not always have simple solutions.

In terms of output, China's manufacturing capacity is the largest in the world. Given the Belt and Road Initiative, and given China's role in the development of infrastructure across a number of African countries, China's ability to impact the environment extends far beyond its borders. China's commitments to its own domestic targets are one thing, but it is important to consider its global footprint as well. This requires strategic thinking and dialogue among nations.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)