Iranian President Hassan Rouhani gives a speech during a rally in the northwestern city of Sabzevar, Iran, May 6, 2018. /VCG

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani gives a speech during a rally in the northwestern city of Sabzevar, Iran, May 6, 2018. /VCG

Editor's note: Guy Burton is a visiting fellow at Lancaster University and adjunct professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Last week's talks to revitalize the Iran nuclear deal, also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) ended on a positive note. But it is not certain that the outcome is determined. There are a number of obstacles that stand in the way of both Iran and the U.S. returning to the deal.

They include several regional actors, like Israel and Saudi Arabia – both important American allies in the region – who oppose a U.S. return to the JCPOA as well as domestic political opposition in both the U.S. and Iran.

Both Saudi Arabia and Israel are disappointed with the course being taken by President Joe Biden. In contrast to his predecessor, Donald Trump, who withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA in 2018 and then imposed additional sanctions, Biden has expressed interest in returning to the deal.

In response, the Saudis have said that any return to the JCPOA should also be accompanied by wider talks about Iran's behavior in the region, of which they want to be a part. As for Israel, Iran has accused them of taking matters further. Last week the Iranian leadership accused Israel of attacking the power system which keeps its nuclear processing facility at Natanz online.

In addition to Israel and the Saudis, both Biden and Iran's President Hassan Rouhani face difficulties at home. There are sizeable constituencies in both countries which are opposed to a rapprochement and see advantage in maintaining their current hardline positions.

In the U.S., the Republican Party is uniform in its opposition to the JCPOA and controls half the Senate, the legislative body shared with foreign policy oversight and say over international treaties. While Biden's Democrats make up the other half of the Senate, the president cannot rely on all of them to support his approach. That makes his pathway extremely narrow.

As for Rouhani, his prestige has been undermined by the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA. That action was a significant blow. Before his election as president in 2013, Rouhani had been one of Iran's top nuclear negotiators. When the U.S. abandoned the deal, questions began to be asked about Rouhani's judgement and that of the more pragmatic faction he represents in the Iran regime. At first, Rouhani countered against the American reimposition of sanctions by cutting back on social subsidies, reallocating investment and funds and pursuing alternative exports like those in petrochemicals to compensate for the loss of oil exports.

The hit to Rouhani's domestic credibility meant that the other principal faction in the Iranian regime – the hardliners – began to grow. For them, the measures that Rouhani was forced to take were worthwhile in themselves, since they highlighted the importance of self-reliance.

In that vein, hardliners also pushed for Iran to increase its production and stockpiling of nuclear material. From the 3.67 percent level of enriched uranium that the JCPOA set as a limit, Iran began to boost production, reaching 20 percent enrichment by the start of this year. This month it increased that to 60 percent. While the increase prompted jitters in the international community – and may have been behind Israel's recent suspected attack – it is still some way off from the 90 percent enrichment needed to produce a nuclear weapon.

While the hardliners may have seen the increase in enrichment as a form of self-protection, the pragmatists around Rouhani may have seen it as a form of leverage. By increasing production while not transforming its nuclear program into a military one, it hoped to show that not only was it able to resist Trump's "maximum pressure" strategy, but also to persuade the other signatories to stick with the agreement and to press the U.S. to return to it.

Yet even if that was the pragmatists' goal, their political position has eroded as that of the hardliners has become increasingly consolidated. In legislative elections in February 2020, they won a majority in legislative elections. A hardline candidate is expected to do better than another more pragmatic one in the presidential election scheduled for June.

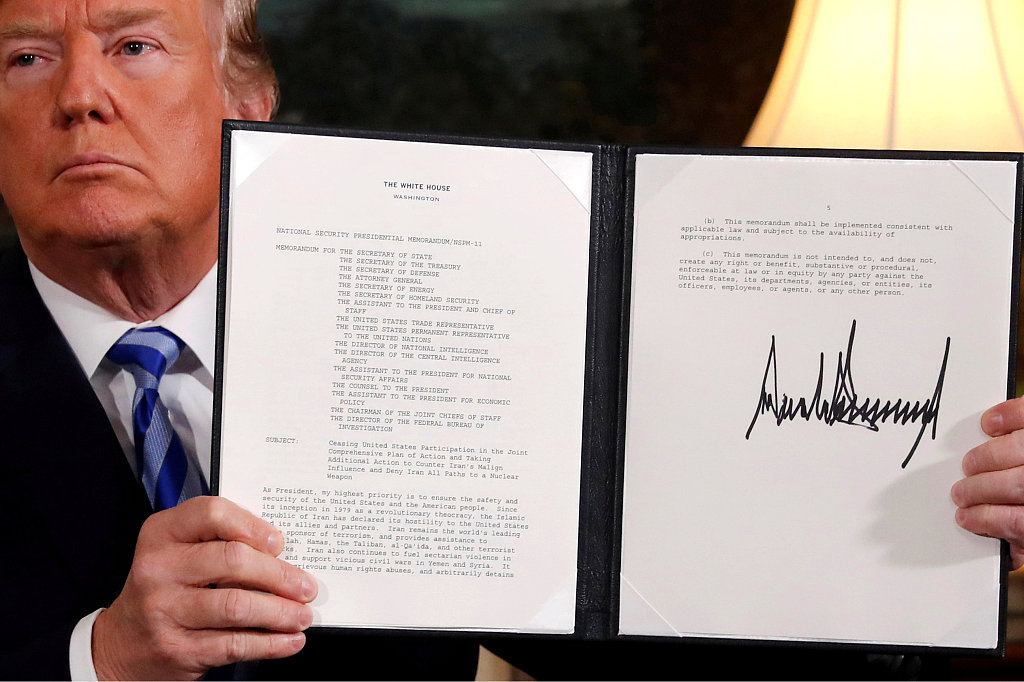

Former U.S. President Donald Trump holds up a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from the JCPOA Iran nuclear agreement after signing it in the Diplomatic Room at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 8, 2018. /VCG

Former U.S. President Donald Trump holds up a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from the JCPOA Iran nuclear agreement after signing it in the Diplomatic Room at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 8, 2018. /VCG

If Iran elects a more hardline president to replace Rouhani, this could spell the end for the current talks that are taking place in Vienna. Consequently, there is a degree of urgency to the talks – or rather "talks about talks." While the remaining signatories for the JCPOA – Britain, France, Germany, China and Russia – met with Iran in Vienna last week, U.S. negotiators were housed down the road in a separate hotel and received representations. In broad terms, the indirect talks focused on two main areas: how to get Iran to return to compliance with the JCPOA and how to remove the various American sanctions.

That this format is taking place demonstrates the difficulties that Biden and Rouhani face. Each president wanted the other to make the first move. Biden had expressed a wish to widen the scope of talks with Iran to cover other areas not covered by the JCPOA, such as Iran's ballistic missile program and its regional activities. Expanding negotiations to cover these issues would have tapped into some of the preoccupations voiced by his Saudi allies. However, Iran's leaders said that such matters were not on the table; instead, the U.S. needed to return to the deal that it had walked away from – and in particular to abandon the sanctions that it had reimposed.

Yet even if the current indirect talks between the U.S. and Iran are ultimately successful and resolve the demands of both sides, there will remain nagging doubts which will go beyond the Iranian presidential election. On the Iranian side, how can the regime be sure that Biden's return to the JCPOA is definitive? How can they ensure that another American president after Biden won't similarly abandon the JCPOA again? On the U.S. side, would a return to the deal and removal of sanctions stem the hardline advance in Iran? If not, how will Biden justify continuing adherence to a deal with a regime that is less predisposed towards talks about Iran's wider regional goals than the current one?

There are no easy answers to these questions. Indeed, finding answers to them goes beyond the scope of the recent meetings in Vienna to involve wider political will and commitment.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)