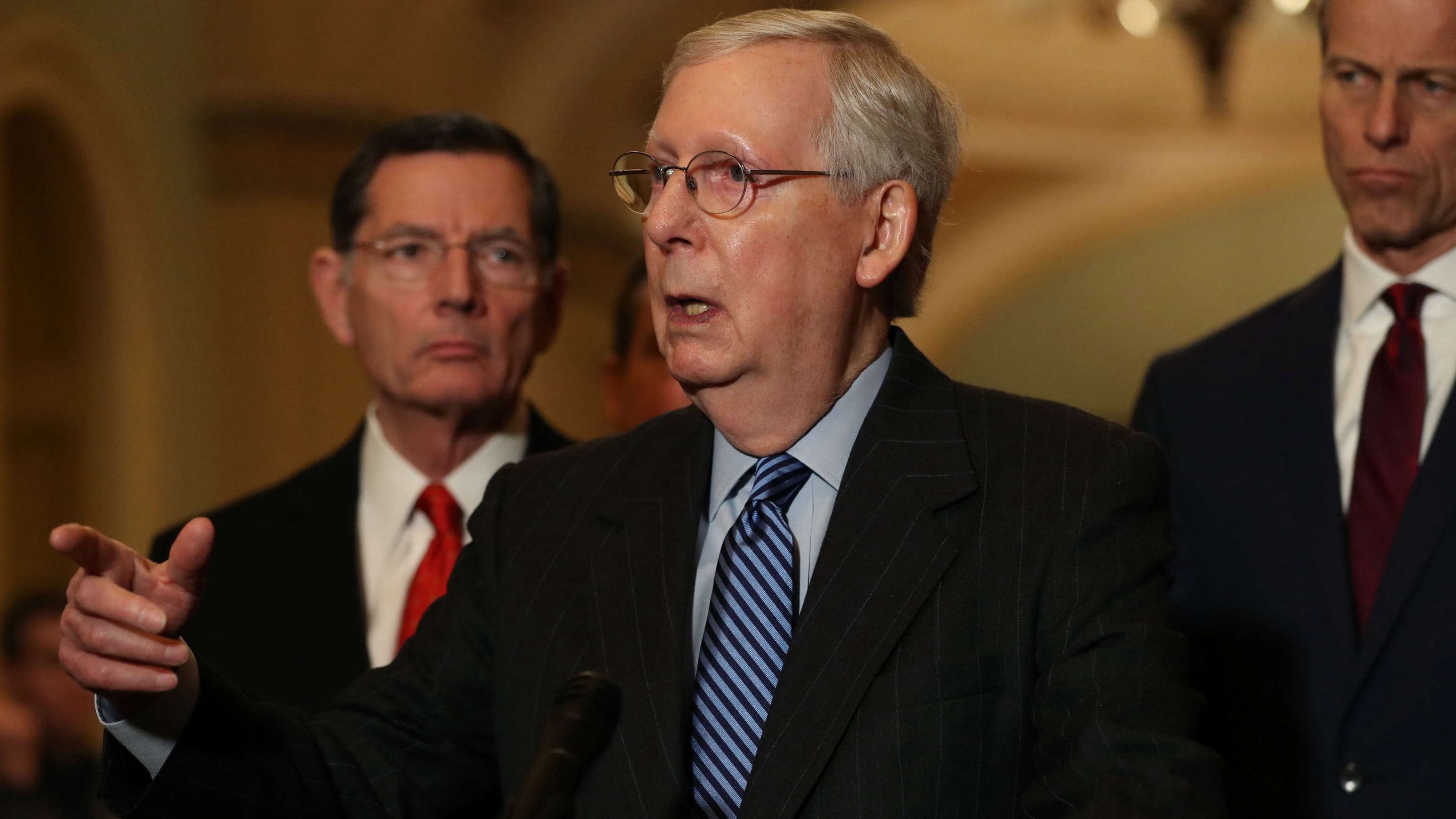

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell faces reporters with fellow Senate Republicans following their weekly policy lunch on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S., January 7, 2020. /Reuters

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell faces reporters with fellow Senate Republicans following their weekly policy lunch on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S., January 7, 2020. /Reuters

Editor's note: Elizabeth Drew is a Washington-based journalist and the author, most recently, of "Washington Journal: Reporting Watergate and Richard Nixon's Downfall." The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Two books recently appeared that shed light on highly important aspects of U.S. politics. Both offer views of the Republican Party's decline from relative unity under Ronald Reagan – first as reflected in Karen Tumulty's astonishing biography of Nancy Reagan; and then as portrayed by a recent Republican Speaker of the House, John Boehner.

Boehner's departure from politics in 2015 can be seen as an omen of what was about to become of his party. Caught between traditional politics and a new wave of radicalism, House Republican leaders haven't been lasting long. Boehner's successor, Paul Ryan, gave up politics after two terms as speaker. The current Republican House leader, Kevin McCarthy, flounders between fear of Donald Trump's continuing influence and pressures from the less radical members who have wanted to break loose from Trumpism.

In his memoir, Boehner tells vivid stories with more than a dash of spiciness. In fact, the book's herky-jerky sections read as if he dictated them. Sometimes, he surgically alters events. For example, in talking of Newt Gingrich having to give up the speakership after the 1998 midterm election, he hurries over the fact that House Republicans had lost seats, for which Gingrich's bombastic style was blamed.

Boehner leaves out altogether that another reason Gingrich had to resign as speaker (he also left Congress) was because at the same time that he was pushing Bill Clinton's impeachment, ostensibly for lying under oath about his sexual affair with a White House intern, Gingrich was having his own affair. Boehner says that he opposed Clinton's impeachment as too partisan and unserious of a matter; yet he went along with it.

Boehner's characterizations of leading Washington figures are deadly – and dead on. Of Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, he says, "He's made a living out of being inscrutable." Of Ted Cruz, one of the most disliked senators by colleagues in both parties: "There is nothing more dangerous than a reckless asshole who thinks he is smarter than everyone else."

Utilizing his selective memory, Boehner at one point criticizes the then-incoming Democratic president, Barack Obama, for not working with Republicans on a stimulus bill. But Boehner omits that Obama, during his first week in office, had said, in an unusual gesture, that he would come to Capitol Hill to discuss it with them. As Obama's limousine was en route to the Capitol, House Republicans announced their opposition to his proposal.

The Republican party's decline as a responsible governing instrument picked up speed during Boehner's speakership. In the 2010 midterm election, Republicans attacked what they sneered at as "Obamacare" (Obama shrewdly embraced the term). Obamacare was so unpopular, Boehner writes, that "You could be a total moron and get elected just by having an R next to your name."

Then U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev sign the arms control agreement banning the use of intermediate-range nuclear missiles, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Reduction Treaty, in Washington, D.C., U.S., December 8, 1987. /VCG

Then U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev sign the arms control agreement banning the use of intermediate-range nuclear missiles, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Reduction Treaty, in Washington, D.C., U.S., December 8, 1987. /VCG

Boehner, catapulted into the speakership by the 2010 election, makes it clear that he felt that quite a number of the Republican members fit into that category. Those members, he implies, ended up forming Trump's base, "the crazy caucus." Boehner has little use for people with no experience in politics coming into Congress believing that they can run the place – and he has a point.

Unlike most Republican officeholders, Boehner flatly blames Trump for the January 6 insurrection. Trump's lingering stranglehold on the party is demonstrated by the fact that Republicans are trying to protect him from an independent inquiry into the Capitol riot, and the fact that the great majority of Republicans still deny that Joe Biden was legitimately elected president. Increasingly, the few relatively moderate Republicans left in Congress are choosing to retire rather than be defeated in a primary by a Trumpian ideologue.

Boehner's speakership represents the dividing line between a Republican party that participated in the give-and-take of politics and one that barely believes in democracy. Tumulty's biography of Nancy Reagan depicts an earlier, more tranquil time. The Ronald Reagan she describes would probably be baffled by what has become of the party he led through two relatively successful, albeit controversial, presidential terms.

Tumulty's book depicts the astonishing and probably unequaled role played in this success by a presidential spouse. Previously, it had never crossed my mind that I would ever compare Nancy Reagan to Eleanor Roosevelt. But despite their yawning differences, the two women had more in common than I ever imagined, at least when it came to influencing the policies of the men they married.

In Tumulty's careful telling, Nancy Reagan understood that famously opaque man better than anyone. She knew when to coach him and when to leave him to his instincts, which often served him well. Ronald Reagan's staff lived in fear of his wife, and dreaded her calls. Those who crossed her, or who she thought weren't sufficiently attentive to her husband's interests, didn't last long.

While Eleanor Roosevelt concerned herself with policy and had influence over some of her husband's decisions, she didn't attempt to co-reign over the White House. She essentially confined her activities to where she had a passionate interest of her own – mainly the plight of the working class.

Nancy Reagan's interest in discouraging the use of dangerous drugs ("Just Say No") was appliqued onto her to try to provide a more serious mien, to offset her image as a frivolous clothes horse. The book makes clear that Nancy sacrificed a relationship with her children to the intense love affair she had with her husband. The book also suggests that the Alzheimer's that Ronald Reagan died of after he left office was present in his presidency.

But Nancy Reagan's influence on her husband did yield serious results. Her crowning achievement, reported by Tumulty in a riveting narrative, was to push the communist-hating Ronald Reagan into making decisions that had much to do with ending the Cold War. Tumulty also makes it clear, though, that Ronald himself, an "idealist," was looking for an opening for dealing with the Soviet Union.

These two books show us the Republican Party at its apex and at its nadir. The question is whether Boehner's bitter and brutal, but not inaccurate, assessment of its current state will obtain in its future.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)