"Be good at math and sciences and you will walk the world without fear" is a common wisdom taught to students in China. For decades, an education in sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) has been associated with academic success and employability.

By contrast, those who have chosen a university major in arts and humanities are no strangers to skepticism over their educational choice, from taunts of not being "smart enough" for STEM to genuine concerns about their job prospects from friends and family.

But a recent paper by four PhDs in economics at China's central bank may just become an official endorsement for the long-held view that arts and humanities graduates contribute less to economy than their STEM peers, or worse – having "too many" of them is "detrimental" to the country's development.

In the candidly penned paper about China's demographic changes published in April, the researchers have recommended China attach great importance to STEM education. But the reasoning that followed raised many eyebrows: "Having too many arts and humanities graduates is one of the reasons why countries in Southeast Asia fell into the middle-income trap."

In China, arts and humanities is a broad category that also includes social sciences and business majors such as law, politics and finance.

Opponents of the statement say economists, who are also part of this diverse group, have overlooked the oftentimes intangible contribution of non-STEM workers to economic and social development.

In fact, China has produced far more STEM graduates than those in arts, humanities and social sciences, as the country consistently invests in STEM research at its top universities known as 985 and 211 projects, in a push to develop its economy through science and education.

A wall honoring China's top scientists is seen at the China Science and Technology Museum in Beijing, September 20, 2020. /CFP

A wall honoring China's top scientists is seen at the China Science and Technology Museum in Beijing, September 20, 2020. /CFP

How a Confucian society became preoccupied with science

Long before scientists and engineers began to get exalted to the status of national heroes for making China a modern country, Confucian scholars had ruled the nation for more than 1,300 years.

In ancient China, there was a tradition of selecting people who were born in privileged families, had good merits and were good at mastering Confucian culture to help the emperors govern the state.

Keju is a well-known ancient Chinese examination system where attendees who outperformed their competitors in reciting and understanding of ancient literature got selected.

The ancient way of selecting officials emphasized proficiency in classic literature over knowledge of science and engineering, though at least four world famous inventions – paper-making, printing, gunpowder and compass – came from China.

The dominant Confucian ideology faced backlash in the latter period of the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912) when the imperial government began to crumble in the face of foreign aggression. This led to the abolishment of the keju system in 1905 as some Chinese young people began to learn foreign ideas and technologies to save the country.

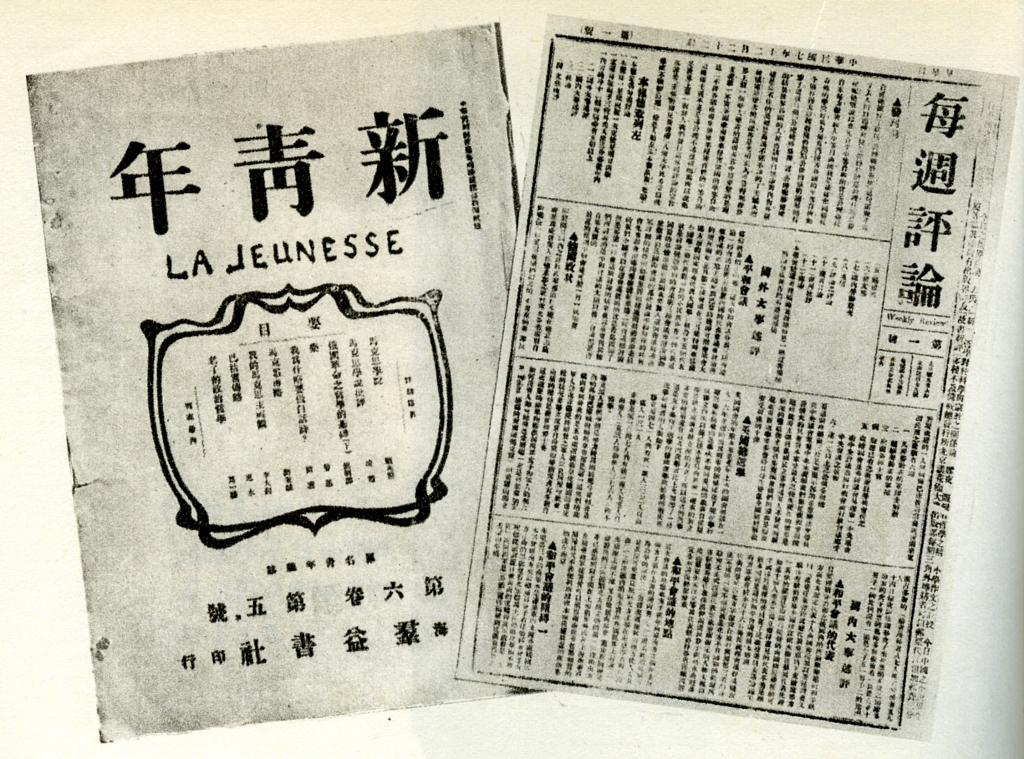

The diplomatic failure of the Nationalist government after World War I brought Chinese students to the streets on May 4, 1919, when "Democracy" and "Science" became a rallying cry in the hope to stop their country from being further colonized by more advanced Western powers.

Newspapers and periodicals from the May 4th Movement /CFP

Newspapers and periodicals from the May 4th Movement /CFP

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the need to rebuild the country elevated the development of STEM to a top priority. Then in the 1980s, former leader Deng Xiaoping famously remarked that "science and technology are a primary productive force," kick-starting China's economic transformation.

The preference for STEM courses has continued to this day. Nationwide college entrance exam data shows enrollments in arts and humanities courses have stayed around a quarter to one-third of those in STEM at Chinese universities in the last decade.

In recent years, however, authorities have stressed the importance of arts and humanities in higher education. In 2018, Tsinghua University, which is considered China's most prestigious school for STEM studies, appointed 18 senior professors in arts and humanities in a bid to encourage the development of these subjects.

"Infrastructure building requires talents in STEM. But when a country is strong and wealthy, the importance of arts and humanities becomes more prominent," Liu Xiao, a professor from the Faculty of History at Tianjin Nankai University, told Chinanews.com.

Liu added that the improvement of a nation's humanistic qualities depends on the development of arts and humanities.

Are arts and humanities degrees less valuable?

Around the world, technological innovation is strongly associated with economic development and workers in STEM fields play a direct role in driving growth, according to a 2013 study by Washington-based Brookings Institution.

Since the 1980s, developed countries like the United States introduced the "skill-biased technical change," favoring skilled over unskilled labor. This made university education a high-return investment and a substantial income boost for STEM professionals.

A similar trend was observed in China during the 1990s when the country embarked on the road to market reforms.

However, there is little statistical evidence indicating that arts and humanities graduates are less valuable to China's economy, according to some academics.

"From an economic point of view, what's more important is the area of the economy that students participate in upon graduation rather than whether they study humanities or STEM," explained Yang Po, an expert in education economics from Graduate School of Education at Peking University.

As the service industry and informal sectors make up a bigger part of China's economy, graduates in arts and humanities are less likely to find themselves disadvantaged, Yang noted.

The Chinese economy is transitioning away from being led by investment and manufacturing to being driven by consumption, services and innovation, according to a 2021 report by global consultancy Mckinsey.

Live-streamer-turned-entrepreneur Viya at a promotional event in Hefei, east China's Anhui Province, April 25, 2021. /CFP

Live-streamer-turned-entrepreneur Viya at a promotional event in Hefei, east China's Anhui Province, April 25, 2021. /CFP

Some of China's top CEOs in the tech industry, including Alibaba's Jack Ma, have their degrees in humanities and social sciences.

The late founder of Apple Steve Jobs famously said about his company's "DNA:" "Technology alone is not enough — it's technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing."

Greater portions of global tech value chains are increasingly accounted for by activities and skills derived from the arts and humanities, whereas many "hard" skills like programming and certain types of engineering will become obsolete and readily automated, according to another study from Brookings in 2019.

Due to rapid technological changes, mismatches between job requirements and university majors are common, and not only affecting arts and humanities graduates, Yang said. Besides, a shift toward general education and the expansion of cross-disciplinary studies make it harder to define a student as strictly humanities or STEM, she added.

"It is a misinterpretation of the paper to say arts and humanities students will affect the economy negatively," Yang told CGTN, referring to the central bank's working paper. "What kind of graduates a country has is largely a result of its economic development, not the other way round."

Having more choices in what to study at university is in itself a sign of progress, because economic development and reduced inequalities lead to more diversity in major choices, Yang said.