This flat strip of pasta, similar in shape to a fettuccine, will curl up into a helix when dunked in hot water. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

This flat strip of pasta, similar in shape to a fettuccine, will curl up into a helix when dunked in hot water. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

Pasta commands a special place in many hearts and kitchen cupboards. But a lot of room can be saved since air takes up much of the space in our favorite shapes.

Consider the hollow tubes of penne, the wide curls of fusilli, and the ruffled edges of campanelle. They offer a wondrous world of culinary possibilities and sauce pairings but require a good deal of packaging destined, in part, to landfills and incinerators.

Now, a team of 17 multidisciplinary scientists from three U.S. and Chinese universities has broken the mold of pasta shapes, cooking up noodles that go from flat to full-figured when tossed in boiling water. Their new designs trim the size of pasta packages and cut back on plastic waste.

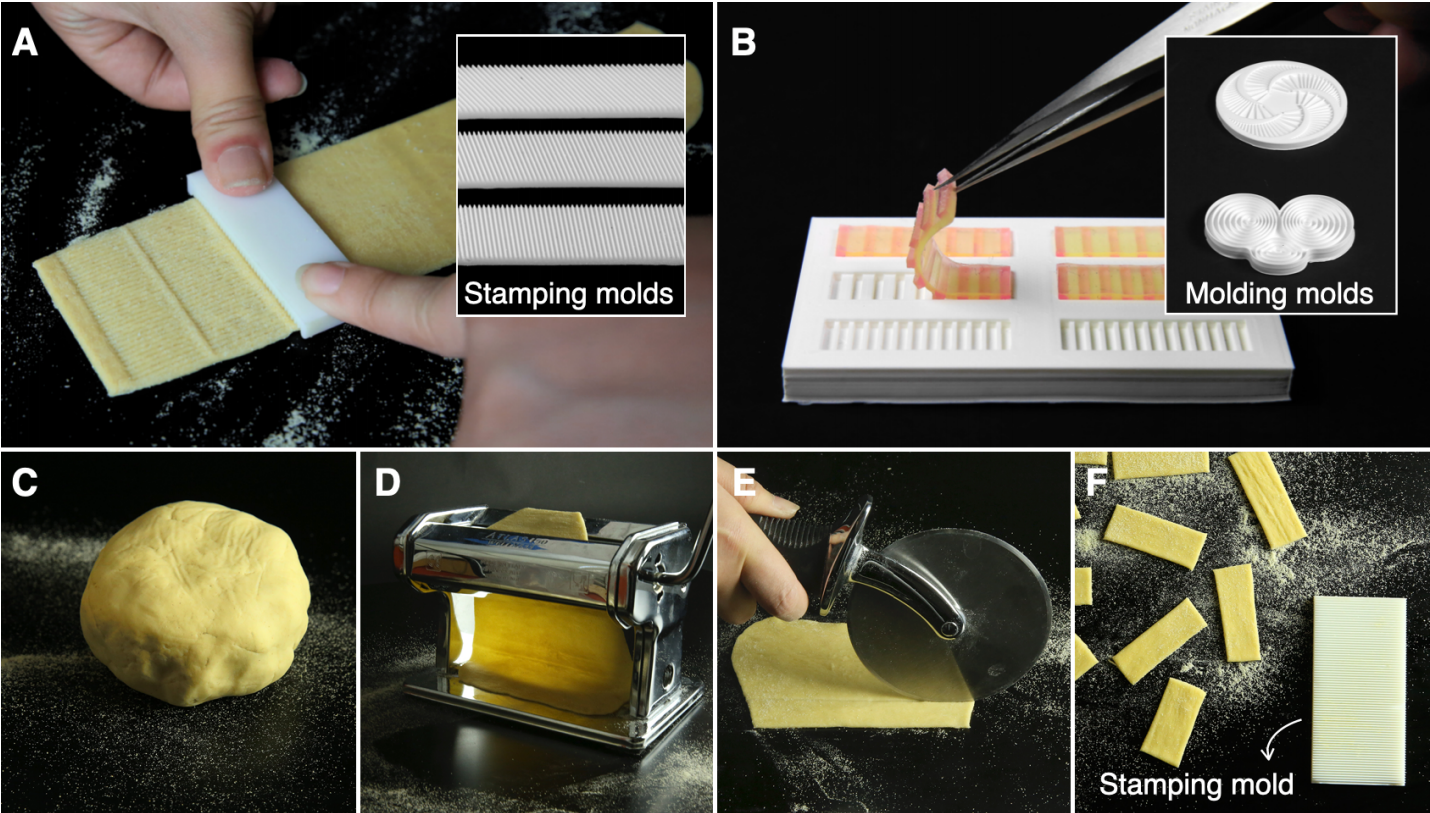

At a Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) lab, the researchers developed this shapeshifting pasta by imprinting tiny grooves onto the surface of rolled dough – a standard mixture of semolina flour and water. The sites of the narrow depressions expanded less than the smooth parts during cooking, causing the dough to swell asymmetrically and transform into three-dimensional structures.

The final shapes didn't spring to 3D life haphazardly. They depended on how and where the dents were placed on the raw dough, as well as their size, the gap between them and the thickness of the base. By carefully controlling these parameters, the researchers succeeded in coaxing the plain-looking sheets and strips to contort into spirals, tubes, waves and saddles in the pot.

When you unbox these pasta sheets, they're flat. But a few minutes on the stove and they'll change into 3D structures. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

When you unbox these pasta sheets, they're flat. But a few minutes on the stove and they'll change into 3D structures. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

Scientists lifted the lid on the designs in a paper published in Science Advances last week, and lead author Tao Ye says the research on the morphing pasta has been simmering for a few years now.

From guesswork to design guidelines

A 2017 food project by Tao's co-authors, who at the time were at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), laid the inspirational groundwork for her work. The "Transformative Appetite" used gelatine and cellulose in two-dimensional edible films that would twist and curl into 3D configurations at the touch of water because of the different response of materials to hydration.

"I was shocked," Tao, a former visiting postdoctoral researcher at CMU and currently an associate professor at Zhejiang University City College, told CGTN of the endeavor.

At CMU, she channeled her curiosity into harnessing the transformative potential of dough in a new project coded "Morphlour," a portmanteau of morphing and flour.

She and her colleagues in 2019 proved that a piece of dough that starts out flat could end up coiling into spirals or closing in on itself when strategically embossed with minuscule grooves at various angles. They whipped up tacos that self-wrap in the oven and fettuccine strips that curve into a heart shape when boiled. But there was a problem: The team couldn't explain the works behind the dough's behavior.

"Morphlour is more like a design-oriented research. We established the goal of realizing the deformation of the dough [but] we constantly [relied on] trial and error to find feasible methods" for the morphing design, Tao explained.

A composite image shows the different stages of preparing the pasta dough and impressing tiny grooves on its surface. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

A composite image shows the different stages of preparing the pasta dough and impressing tiny grooves on its surface. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

In the just-published paper, the group worked to clarify the underlying morphing mechanism and drum up design guidelines that moved their research from experimental to theoretical.

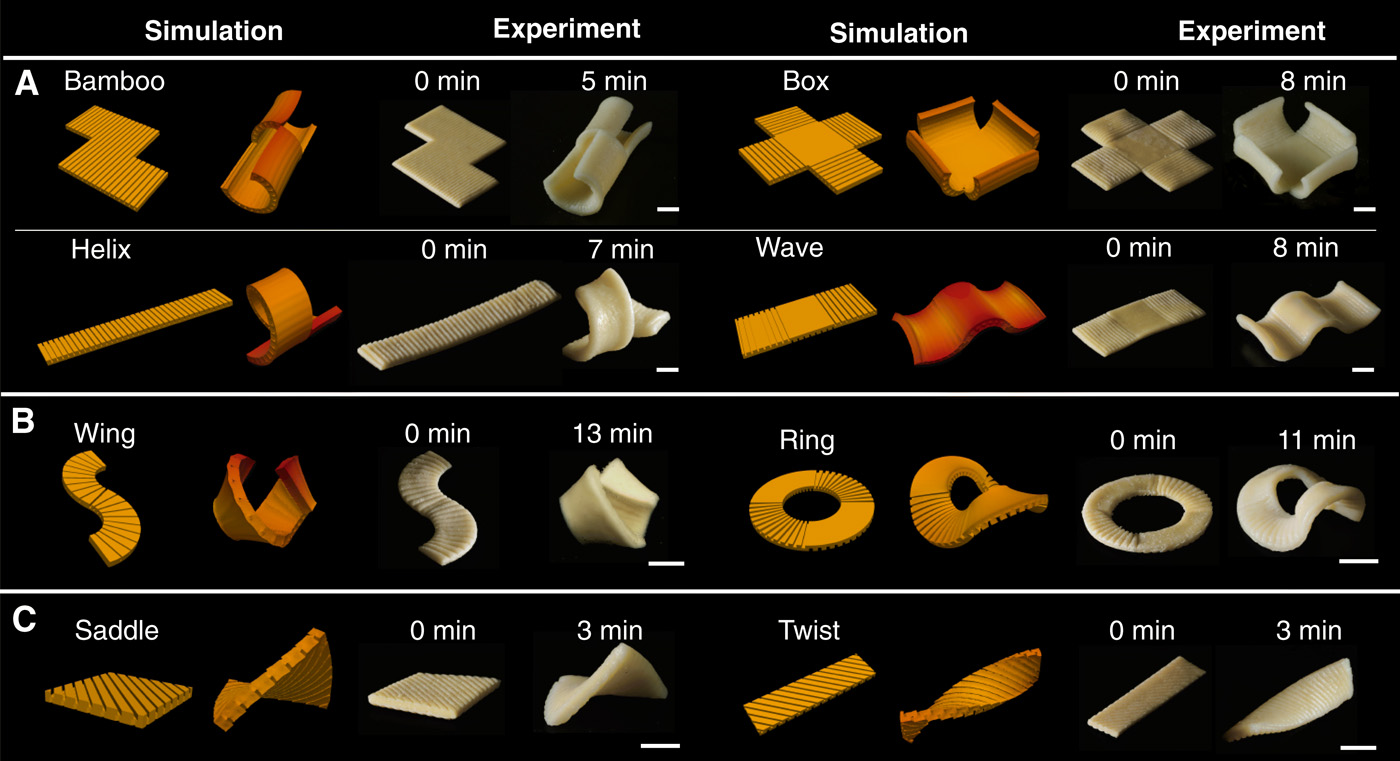

Computer simulations developed by Teng Zhang, an assistant professor at the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Syracuse University, predicted how different pasta designs would look based on the geometric features of the grooves.

For example, parallel patterns led the flat pasta to twist into a helix. Radial patterns gave rise to a cone when pressed on one side of the uncooked dough and a ring shape when stamped on both sides.

"We proposed the guidelines of making helices, cones, and [other] complicated shapes through a combination of them. This rationalizes the design principle for non-designers, for example, engineers," Teng, also a co-author of the study, told CGTN.

"In the previous Morphlour work, the design was pretty much based on the designer's intuition and experience," he explained.

Researchers used computer simulations and kitchen tests to experiment on different pasta designs and their morphing behavior during cooking. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

Researchers used computer simulations and kitchen tests to experiment on different pasta designs and their morphing behavior during cooking. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

And while researchers fished out familiar pasta shapes at the end of their kitchen test, there is still a long way to go before they can turn the unassuming strips into all the pasta varieties already on the market or successfully tackle complex shapes. As they explained, some designs are harder to reach from a flat state because of their curvature and the swelling index of pasta (how much noodles can puff up in water).

Pasta on a mission

There's more to the programmable pasta than the incredible engineering feat at play, with researchers touting its potential green credentials.

The world doesn't seem to be getting enough of this staple of the Italian cuisine. Even before pantries overflowed with spaghetti, macaroni and rigatoni last year in our collective pursuit for shelf-stable comfort food amid the coronavirus pandemic, factories had been churning out record amounts of pasta.

In 2019, global production reached nearly 16 million tonnes, more than twice the output 20 years earlier, according to the Rome-based nonprofit International Pasta Organization. That's a lot of pasta but also plastic for the bags, given that the commercial type is usually mechanically formed into its intended 3D shape on the production line.

Plastic is the most common type of packaging for pasta. /CFP

Plastic is the most common type of packaging for pasta. /CFP

Amid a sustainability race in recent years, pasta makers and grocery stores have hatched a range of eco-friendly ideas for their products. In 2016, British supermarket chain Waitrose introduced packaging made of 15 percent peas and pulses discarded during the production of its gluten-free fusilli. In 2020, Barilla, the world's biggest pasta company, announced it is putting an end to the plastic window on the front of its boxes and switching to 100-percent recyclable cases made from paper-based materials. And just last month, UK grocer Aldi said it is doing away with all packages, selling loose pasta from dispensers in a trial run.

Tao and her colleagues opted to think outside the (pasta) box, turning their attention to the content instead of the container.

"People make food and eat food every day, mostly following the menu. But few think that food can be designed," she said.

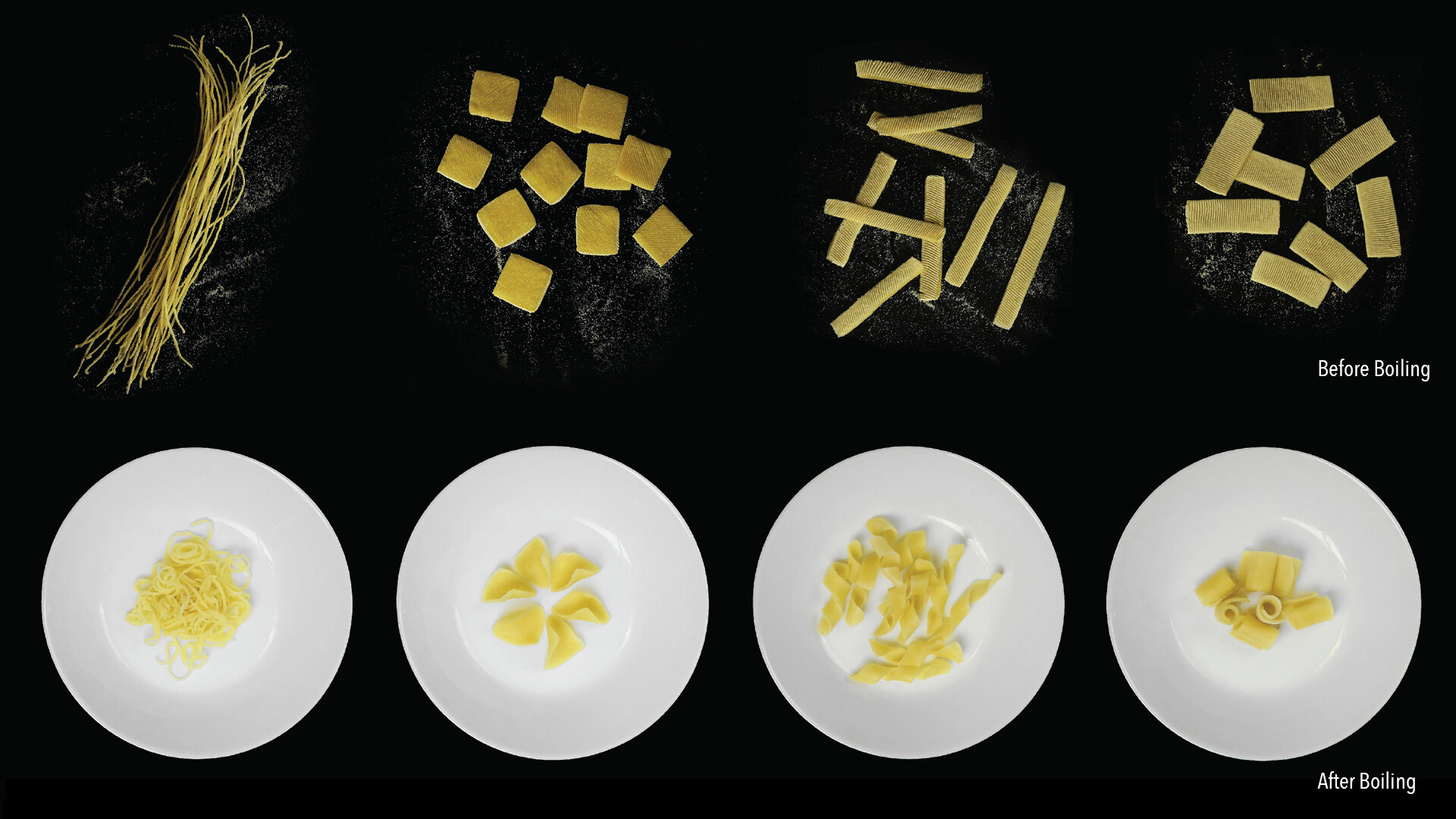

The convertible carb concoctions occupied between 59 percent and 86 percent less volume in their flat form compared with their cooked shape. Slashing the packing space reduces packaging materials, and consequently waste. It also renders storage and shipping more efficient and potentially less costly.

The team also estimated that the minimalistic pasta could have a smaller carbon footprint, as it needs between seven and 12 minutes on the stove until it is al dente – marginally faster than most regular shapes.

The flat-packed pasta could also come in handy in situations limited by spatial constraints, like in disaster-hit areas or space travel.

Volumetric calculations from the 2019 Morphlour research comparing flat shapes and morphed shapes in four designs. Depending on the 3D structure, 41 percent to 76 percent of packing space can be saved. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

Volumetric calculations from the 2019 Morphlour research comparing flat shapes and morphed shapes in four designs. Depending on the 3D structure, 41 percent to 76 percent of packing space can be saved. /Morphing Matter Lab of Carnegie Mellon University

Taste tests have garnered positive reviews, researchers say. Tao gave the flat-packed pasta a go in the outdoors while on a hiking trip and found "no difference" in the mouthfeel than what she's used to. But the rest of us might have to wait a little bit longer for a taste.

Scaling-up and consumer testing are crucial to take the morphing pasta into commercialization, said Wen Wang, a former researcher affiliated with the Morphing Matter Lab at CMU and a co-author of the paper.

"It is hard to predict an exact time, but it could be six months to two years if resources are available," she said.

When that day comes, it'll be a new dawn of "pastabilities."